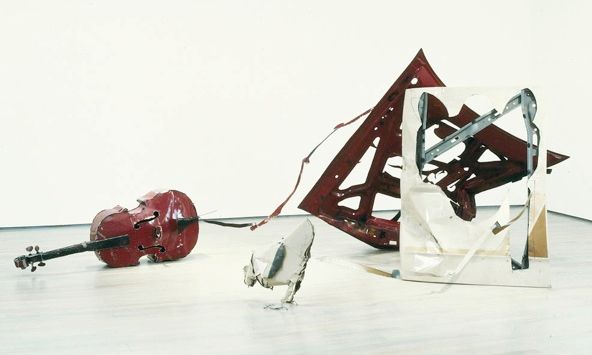

Bill Woodrow's Cello/Chicken (1983) was offered by Roseberys for £1,000-£2,000 before being withdrawn

A group of eight sculptures by the British artist Bill Woodrow were withdrawn from a sale that took place earlier this week at the London auction house Roseberys, after their conservative estimated prices caused parties involved in the artist's market to intervene. The works were among 40 offered from the collection of the British advertising and communications firm Saatchi & Saatchi.

Saatchi & Saatchi, once the world's largest advertising agency, was co-founded by the highly influential Iraqi-British collector Charles Saatchi and his brother Maurice. The brothers were ousted from the company in 1995, but much of its collection, including the works offered at Roseberys, was acquired during Charles's tenure, and around the same time that he was rapidly buying and exhibiting work by UK artists, including those associated with the Young British Artists (YBAs), and the New British Sculpture movements.

Central to this latter group is Bill Woodrow, a Royal Academician and Turner Prize-nominee known for creating work from scrap materials. Woodrow had by far the most works in the Roseberys sale, which also featured Lucas Samaras and Julian Opie. Almost all the eight Woodrow sculptures that were consigned had notable exhibition histories: for example, Cello/Chicken (1983), an expansive metal installation sculpture made from car bonnets, had been shown in a number of international institutions including the Louisiana Museum in Denmark in 1986, and was even the cover image of a text by the curator Alistair Hicks on British contemporary art, published in 1989.

Yet despite these factors, as well as their large sizes, estimates for all of the sale's Woodrow works were notably very low. Most were estimated at around £1,000-£2,000, with one carrying a low estimate of £800. While Woodrow's secondary market has never reached the heights of his New British Sculpture peers such as Antony Gormley, large works of his have typically fetched in the mid-to low-five figures at auction.

"This is an artist who has represented his country at five biennials. How on earth did someone arrive at a starting price of £700?," says Jessica Smith, who formerly worked at the New Art Centre in Salisbury, where Woodrow had a solo show in 2016. "Some of these works are not too dissimilar to his sculptures in the collections of Tate and MoMa."

This position is supported by the fellow New British Sculptor and Turner Prize winner Richard Deacon. "It would be have been extremely destructive to Bill's career to have had these works dumped in a minor auction house," he says.

According to Deacon, the low sums for which Roseberys offered the works drew alarm bells among key figures associated with Woodrow's market. The Art Newspaper understands that this led to a private deal being struck between the consignors and the British dealers Jacob Twyford, director at Woodrow's gallery Waddington Custot, and Charles Booth-Clibborn to withdraw the works from the sale. Further terms of the deal are not known. Both Twyford and a spokesperson for Waddington Custot have declined to comment. The Art Newspaper understands that Woodrow was aware of the sale, but is unwilling to comment on the situation.

A spokesperson for the auction house says: "Roseberys acts with strict confidentiality, and it is important to note that it never reveals the personal details of buyers or sellers."

Deacon adds that a comparable situation happened to him in the 1980s when Charles Saatchi attempted to unload a number of his works that he had bought to exhibit alongside those by Lucian Freud and Richard Wilson. "Luckily", Deacon says, Nicholas Logsdail, the founder of Lisson gallery, stepped in and offered Saatchi a deal, and eventually "relocated the works" to a number of museums and institutions. "No one was harmed," Deacon says, "and it meant that Charles realised a reasonable return on the money that he spent".