[ad_1]

But the work was also dangerous. On May 6, 1968, Armstrong performed his 22nd flight of Lunar Landing Research Vehicle No. 1 at Ellington Air Force Base outside Houston. Five minutes in, he lost control of the vehicle due to a loss of helium pressure and was ejected 200 feet above the ground as the vehicle crashed and burned on impact.

Later, he would say that the Eagle, the spacecraft he and Aldrin landed on the moon, handled just like the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, which he flew more than 30 times before Apollo 11.

“That of course gave me a good deal of confidence — a comfortable familiarity,” Armstrong said at the time. “It was a contrary machine and a risky machine but a very useful one.”

The woman in the room

On July 16, 1969, the day of Apollo 11’s historic launch, rows of men in shirts and ties lined the consoles inside Kennedy Space Center.

But one woman stood out — 28-year-old JoAnn Morgan.

Morgan needed to be in the room to alert the test team if anything went wrong, but she had to get special permission to be there. Morgan also endured obscene phone calls and had to use the men’s restroom because there weren’t any for women.

She went on to pave a path as one of NASA’s first female engineers. After Apollo 11, Morgan’s career took off. From 1958 to 2003, she continued to break barriers and became the first female senior executive at the Kennedy Space Center.

And the woman who helped land men on the moon

Margaret Hamilton was the software engineer who developed the onboard computer programs that powered NASA’s Apollo missions, including the 1969 moon landing.

But the software cleared all tasks each time it neared overload, allowing the astronauts to enter the landing commands. The software’s emergency preparedness is thought to have helped save the mission, Hamilton wrote.

For the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, Google unveiled a giant tribute to Hamilton in California’s Mojave Desert: More than 107,000 mirrors were positioned to reflect moonlight and form her image for one night on the grounds of the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System, the world’s largest solar thermal power plant.

Armstrong was ‘Mr. Cool’

“And he said, ‘Well, I probably would have said, “Say again Houston, I didn’t copy that,” and gone ahead and landed.’ And he would have. And he would have done it. That’s how much confidence that I and the other people involved had in Neil Armstrong. He could do the impossible,” Bostick said.

It was this dynamic that earned Armstrong the nickname “Mr. Cool.” Some people called him “First Man.”

“But what people maybe don’t know about First Man was that First Man was one marvelous proponent of the virtues of the United States and spread those all over the globe,” Collins said.

What the moon landing looked like

The historic moment of Armstrong stepping on the moon roughly six hours later was actually quite blurry as it was seen on TV. The shot came from a camera attached to the lander.

But what many don’t know is that Aldrin was filming Armstrong, too; he captured those monumental steps from above, while inside the lander, looking down the ladder at Armstrong.

“Strangely enough, it looks fragile somehow,” Collins said. “You want to take care of it. You want to nurture it. You want to be good to it. All the beauty, it was wonderful, it was tiny, it’s our home, everything I knew, but fragile, strange.”

Collins wasn’t the ‘loneliest man’

While Aldrin and Armstrong landed on the moon, Collins kept circling it. Once Armstrong and Aldrin were finished, he would rendezvous and dock with the Eagle after it left the lunar surface.

“It was a happy home. I liked Columbia,” he said. “It reminded me, in a way, of almost like a church or a cathedral. It had the apse, the three couches, and then you went down into where the altar was. That was the guidance and navigation system. And it was laid out almost like a cathedral. And I had hot coffee. I had music I could play if I wanted to. I had people to talk to on the radio, sometimes too many people talking too much on the radio. So I enjoyed that interlude. Being by myself in a machine up in the air somewhere was not unknown to me, and so everything was working well within Columbia, and I enjoyed it.”

A meal on the moon

The Apollo 11 astronauts, meanwhile, had more than 70 food items to choose from. Among the foods that were eaten on the surface of the moon in the lunar module were beef stew, bacon squares, date fruit cake and grape punch.

Astronauts roaming the lunar surface also had drinking devices with water installed in their space suits, and if they were peckish they could nibble on the high nutrient food bar in their helmet.

400,000 people worked on the Apollo 11 mission

The full triumph of Apollo 11 doesn’t just belong to the astronauts. It also includes the 400,000 people that supported the mission across the country, mainly at Johnson Space Center in Houston and Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Young college graduates flocked to NASA after Kennedy’s 1961 speech.

During Apollo 11, everyone who could possibly be needed or called upon during the mission was in a room at Cape Canaveral or Houston. They each had a specific task. And they all wanted to be there. They jockeyed for places to plug in their headsets and sat on steps.

“It was a can-do attitude,” said Bostick, the flight dynamics team leader. “We were very sober and somber in what we were doing. We took it very seriously. We worked very hard. But at the same time it was fun, we really didn’t think of it as a job, even though we were working 12 hours a day at least, six days a week. We didn’t understand the magnitude of what we were doing.”

Mission Control was more than a room

The small room depicted in movies often shows team leaders sitting at consoles and staring at monitors.

But to accommodate the thousands of people needed, team members were in various control rooms, staff support rooms, back rooms, simulators, computing complexes and the projection room known as the “batcave.”

NASA had an art program

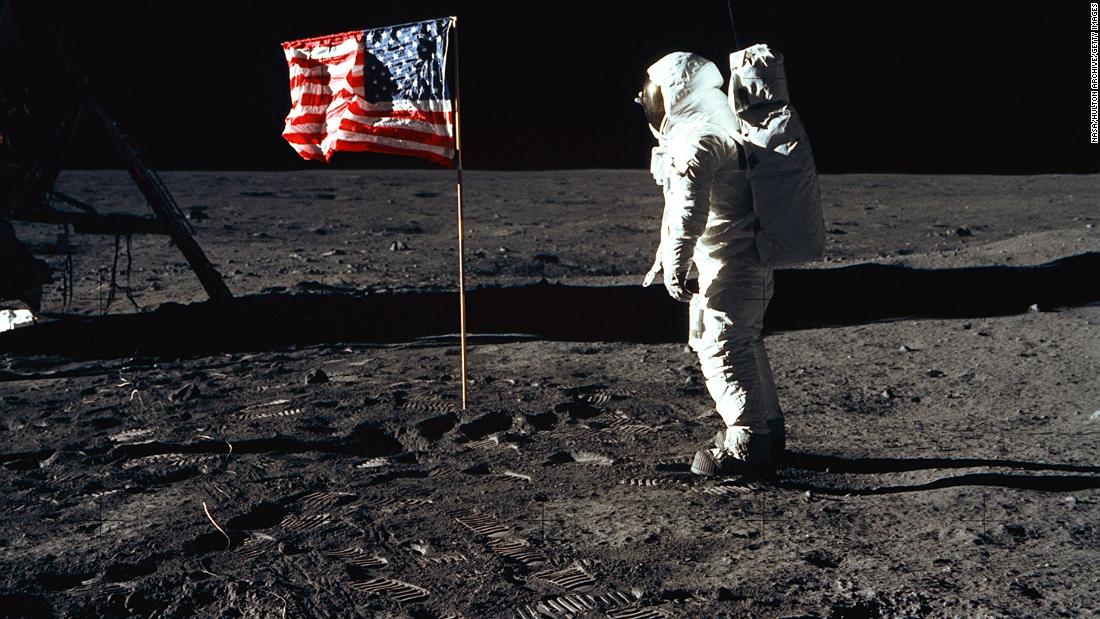

Norman Rockwell’s famous painting of astronauts Gus Grissom and John Young originated during the early days of the program, in 1965. Andy Warhol painted a silkscreen series of Aldrin standing on the moon next to the American flag.

Apollo 11 opened the door to space

“The Apollo program made space accessible to us,” said Mason Peck, former NASA chief technologist and professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Cornell University. “Those brief visits to the moon set a high bar for NASA and for all space exploration since.”

“It really built a infrastructure that didn’t exist,” said Marshall Smith, NASA’s director of human lunar exploration. The program created a boost for technology and economy and allowed for the return of lunar samples to Earth, enabling a better understanding of our solar system’s history.”

Thom Patterson, Sarah-Grace Mankarious, Natalie Angley, Scottie Andrew and Katherine Dillinger contributed to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link