[ad_1]

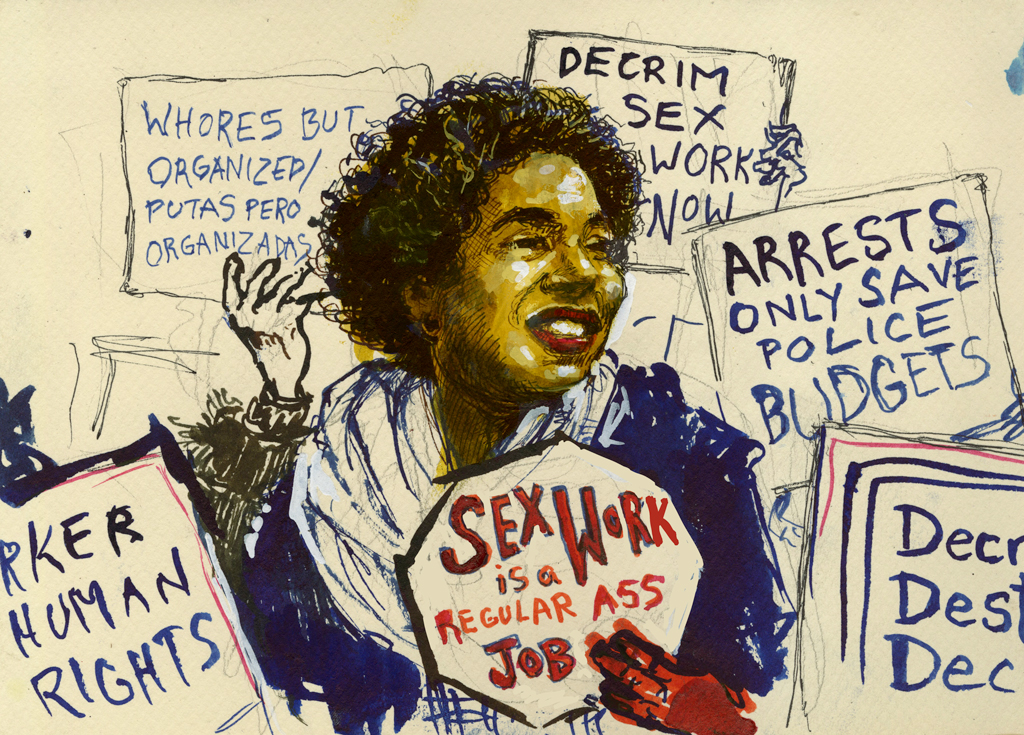

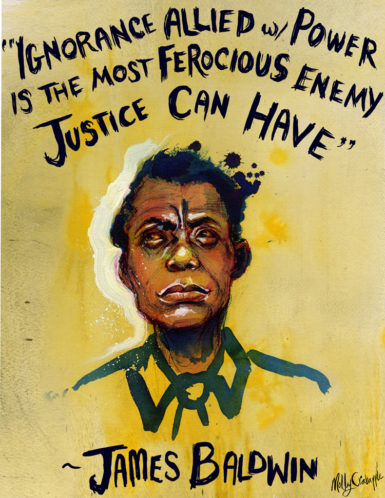

Molly Crabapple, illustration for Whores but Organized, 2019.

©MOLLY CRABAPPLE/COURTESY THE ARTIST

Molly Crabapple is art’s Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Beyond being a Democratic Socialist with Puerto Rican and Jewish roots, Crabapple is a very confusing adversary for the conservative establishment. As a fearless, glamorous, direct, and endlessly competent woman, she is an eminent danger to entrenched power while being a captivating icon of disruption. She entered art as a model and founded a subculture of burlesque life-drawing classes while creating her opulent, life-affirming, character-driven, intoxicating artistic style. She has contributed her instantly identifiable artistic gifts to activist movements from Occupy Wall Street to the ongoing fight for sex workers’ rights. And through her writing and illustration work in the New York Times, Paris Review, and Newsweek, and on CNN, Crabapple has advocated for disempowered people. In collaboration with Marwan Hisham for her 2018 book, Brothers of the Gun: A Memoir of the Syrian War, she provided a poignant portrait of war’s human cost, a project that involved her learning Arabic to travel through Turkey reporting, in visual form, on the daily realities of Syrian refugees. In her art, activism, and openness in interviews, she has been candid about inequities, functional realities, barriers, and the need for radical change long before the zeitgeist went woke.

This interview was a long-overdue reunion, curled up together over many cups of strong loose-leaf tea, in Crabapple’s captivatingly ornate Lower Manhattan studio/home. We first met in Berlin, through the artists David Nicholson and Clayton Cubitt, over a decade ago. Her portrait of me (seen here) is one of my most cherished objects and she recently cast me as “Madonna in a Fur Coat,” for her illustrated reflection on Sabahattin Ali’s iconic 1943 novel of love in Weimar Berlin in the New York Times. This conversation is typical of our catch-ups, only with “record” pressed on.

Ana Finel Honigman: I think one of your many contributions to culture is your longstanding openness about money. With all the horrors of the recent government shutdown and a shift in conversations about peoples’ financial insecurities in the arts, there is a new transparency appearing. Instead of euphemisms like “you don’t get involved in this for the money,” we are gaining a culture with real information. You’ve always been one of the first and few artists to talk openly and purposefully about money. You talk about how money flows and doesn’t.

Molly Crabapple: Yes, well, what people generally think of as the “high end” “fine art” world has such a hypocritical attitude about money. I don’t know how a field that is based on selling luxury objects for millions of dollars, essentially as investment vehicles, is also so unwilling to speak about how, and how little, people get paid. The entire industry is sheer obfuscation. Even the way an artist actually gets a New York gallery is obscure to me—I still have no idea how it happens, except vague ideas about connections born from Yale MFA programs. Getting started as an artist is wildly unsustainable, unless you already have a financial cushion, which might come from a trust fund or sex work or a rich spouse. The whole financial model for gallery solo shows is this: You work for a year, generally paying for materials out of your own pocket, to put your art in a room for a month. Then, if some pieces sell, you get half the money. If they don’t, you probably don’t get to do it again. That’s a terrible model. Someone much smarter than me once compared the way art rises in value to a sort of proto-blockchain ledger, where the things that determine the value of each piece of artwork are the previous transactions and opinions of rich people about that work. The art itself doesn’t really matter. It is just a tool for holding value. There are no actual standards of good and bad work. Bitcoin functions even though there is no physical object known as a Bitcoin, and I often feel that the art world could function without any physical object known as art.

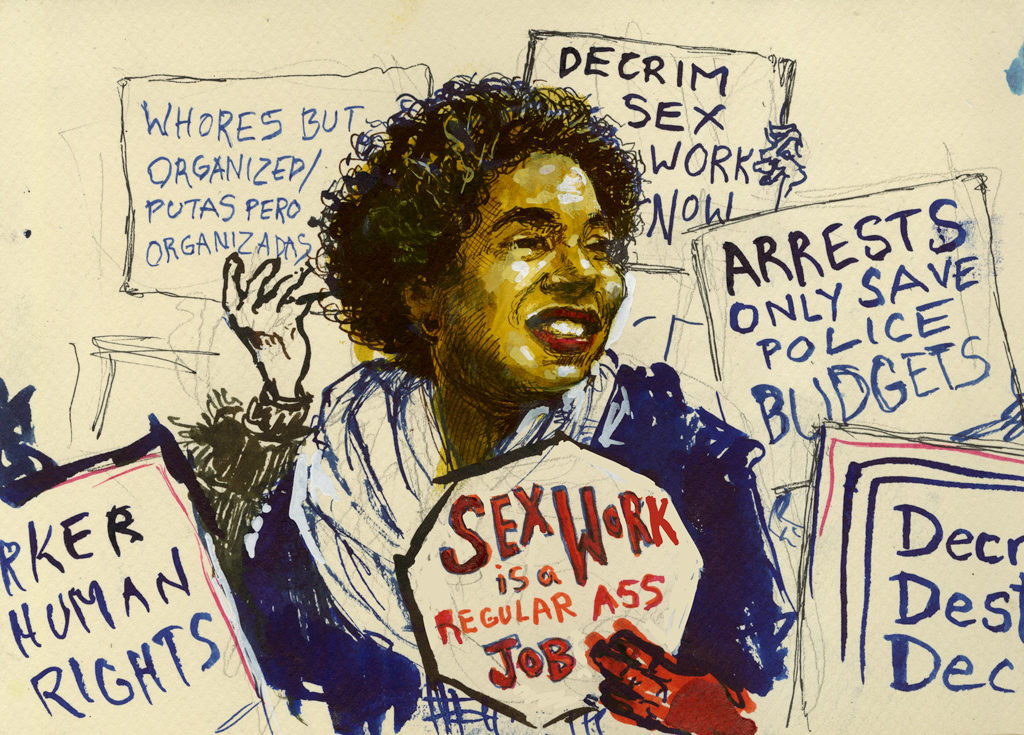

Molly Crabapple, Portrait of James Baldwin, 2017.

©MOLLY CRABAPPLE/COURTESY THE ARTIST

Those intangibles are unsustainable. Transparency is spreading, which is necessary and overdue. Did you read Giulia Mensitieri’s book, Le Plus Beau Métier du Monde? It exposes what we talked about when I was writing often for fashion magazines: multiple tiers of fashion workers are “paid” in clothes, access, or exposure. Looking to survive, on a fundamental substance level is seen as shameful and vulgar, but sunlight on these issues might be changing that.

The assumption is you’ll be in the right milieu to meet a rich guy.

Right, get a Ph.D. to earn an Mrs.

Exactly.

It really seems like this always falls on women, too. The Guerrilla Girls exposed labor abuses in institutions, not just issues of representation within the art world.

It’s hard for me to say, honestly, because I am not really within the art world. By many gatekeepers, I am still not considered a fine artist. Lately, there’s a trend in the art world called “social practice art,” which is supposed to be art that engages with activism—but rarely if ever do I see artists who contribute to actual social movements having their work featured in the big shows of social practice art. It’s almost as if, for the work you make to be considered “art,” you have to step into another scene, in this case activist art, and do what they do but badly. This also relates to the huge rift that exists between contemporary art and people outside of the art world. Most people can tell you their favorite musician or writer—but, with a few exceptions, could they do the same with contemporary artists? So much contemporary art is incomprehensible to anyone without a background in art criticism or theory. People without that background feel intimidated, even ashamed, for not getting it. And much of the art world looks down on the street art and illustration and comics that so many people cherish. Obviously, the state of arts funding in America is shameful, and it’s horrible that, unlike in Europe, there’s almost no state support for individual artists to do their work. However, if artists are going to do work that is deliberately obscure and tailored for a milieu that you feel like you need an MFA to enter, they can’t blame people outside the art world for not seeing their value and not caring if they lose funding.

Most political art is illustration.

Exactly, because illustration is one word for art that people like.

Social practice work that describes issues without contributing to change is the wrong kind of illustration, whereas your work, like Barbara Kruger’s, ends up on protest signs. That’s active art.

Political art should be out in the world. On the walls. On the streets. It’s cool to have political art in the gallery because it might sell, and artists need to make money and also because the art is beautiful and should be appreciated for its own sake. But I don’t think the vast majority of art, in the context of a New York gallery, is doing actual political work. It’s just hanging on the wall like a butterfly. Which is also fine—artists, just like anyone else, are under no obligation to spend their days Creating Work for the Revolution, and it would be a thin, stagnant life if that were all they did. But it’s grandiose to believe you can change the world by hanging paintings in what’s essentially a luxury-goods shop.

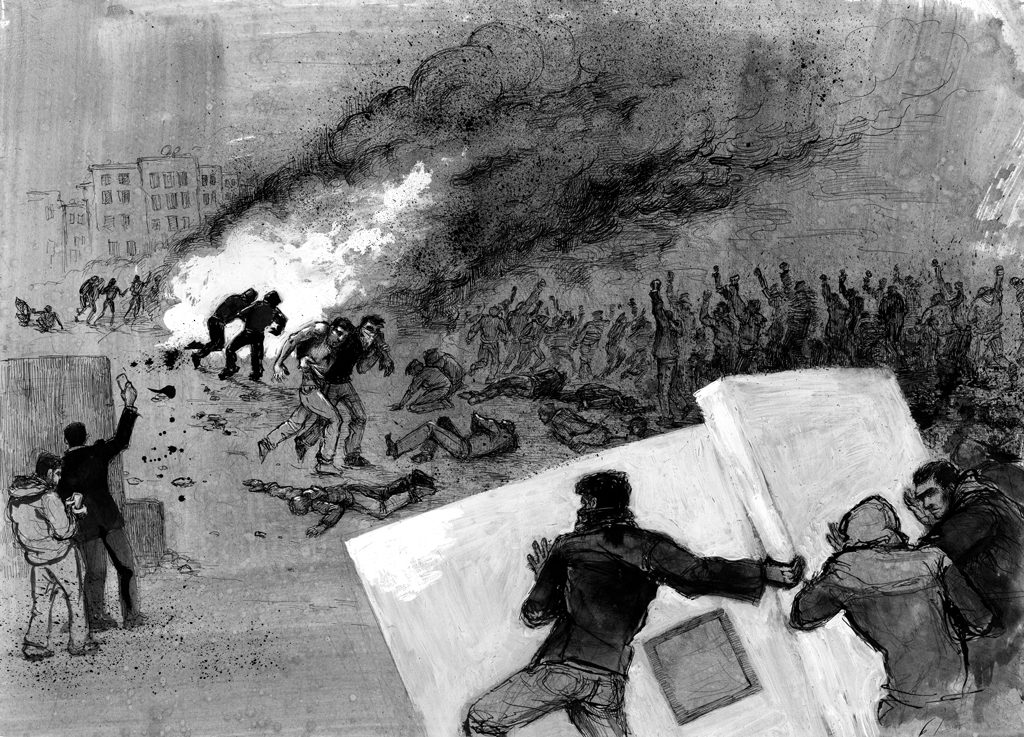

Molly Crabapple, A Protest After the Murder of Ali al-Babinsi in Raqqa, illustration for Brothers of the Gun, 2017.

©MOLLY CRABAPPLE/COURTESY THE ARTIST

Well, I think political art belongs in both. The David Wojnarowicz show at the Whitney was one of the most intense experiences I’ve had in recent memory, as was Sarah Lucas at the New Museum, but also the protest signs from the Vietnam era that the Whitney showed not long ago. What made those works, all of them, so significant was that the museum honored how the work created significant change far beyond its art context. Someday, hopefully very soon, I see the Jewish Museum doing a follow-up to their Art Spiegelman show with a retrospective of your work.

That would be lovely. Art Spiegelman is an inspiration and friend. I hope for more people like him to break through, but the art that people interact with in their lives largely hasn’t been respected enough by the people who write the histories of contemporary art.

In terms of my own career, how I’ve made a living, I guess where I’m different from many fine artists is that, because I did not have a gallery until quite recently, I’ve always sold my work predominantly to non-millionaire non-specialist non-collectors. My work appealed to people outside of the art world enough for them to want to own it without any authority figure telling them it was good. That’s a major way I’ve supported myself, ever since I was 18 and drawing people’s cats for 20 bucks a pop. My friend Travis Louie also says, “It isn’t art if you can’t tell that it’s art in a tag sale,” i.e., it’s only art if it holds up when not surrounded by a shiny white carapace of money.

And artists aren’t immune from having power corrupt them. A few years ago, an iconic feminist artist living in Berlin, whose work exposing social injustice was groundbreaking, posted an ad for an unpaid internship where she demanded applicants hold higher degrees, speak several languages, and essentially work full-time. The line about the role being unpaid was, obviously, at the end. The story of NYU professor Avital Ronell’s emotional abuse of her doctoral student was, to me, among the most relevant cases in the #MeToo movement because it highlighted how power corrupts. Paulo Freire, in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, made the point that individuals representing oppressed groups are always vulnerable to becoming oppressors, however good their initial intentions.

Molly Crabapple, Self-Portrait, illustration for Drawing Blood, 2015.

©MOLLY CRABAPPLE/COURTESY THE ARTIST

I have a full-time assistant and, call me crazy, I think that anyone you hire needs to be paid a decent enough salary to live an adult life, as well as to have health insurance. I don’t think being an artist is an excuse to expect your assistants to either have a trust fund or to live in poverty just for the pleasure of working for you.

That’s a cult. Moving away from the larger world to your own practice and techniques, something I remember us discussing years ago, when we met, was your habit of keeping very regular lists. You’ve always had a clear vision of where you were going.

I’ve always kept to-do lists. I’ve always been very stringent about keeping lists and books of plans. I’ve been doing this since I was 10 years old. Part of it came from escapism. I was a bad child, and just . . . bad at being a child. A total weirdo, always in trouble. I loathed every minute of school. Making these lists was a way of imagining the life I would have when I was old enough to be free of being a child. For instance, I would make myself study French because I had this idea that I would study at the Sorbonne someday (this never came to fruition). I was 11, hiding in a corner of a library and making myself study the pluparfait, that’s how I dealt with being such a miserable little horror.

You’ve described my child identity perfectly. I recently went through storage and found notebooks of meticulous, mundane records I made for my future self. Thankfully, I, as my adult self, am genuinely interested in what I ate when I was 10. I am grateful that I had that borderline neurotic impulse to be my own historian. You, though, were preparing for the future while I was just satisfying a pre-mature nostalgia. Do you feel like the childhood self you were would recognize your present self as her goal?

Yes. In a lot of ways, yes. I definitely think so. All I wanted to be, at that age, was an artist and a writer. I wanted to be cosmopolitan and live in Europe. I never did that . . .

You did. Not permanently but enough to count.

I spent a few months on and off working at Shakespeare and Company between ages 17 and 19, which I was very, very lucky to be able to do, and which provided me a free bed in Paris. If I had it to do over again, I’d have spent even more time. While I realize that it is a massive privilege to even be able to go to Europe at that age, at the time living there, at Shakespeare and Co., was incredibly cheap, much cheaper than if I had stayed living at home. Sometimes things that seem “unrealistic” or “impossible” aren’t—they’re unconventional but can be done.

I think this almost daily now. Since I’ve moved to Maryland, I talk to people about the previous lives that I’ve lived in Europe for almost 20 years, and most are taken aback or wistful that I left America and created an existence for myself, but moving to Berlin was less expensive than a car. A graduate degree in the U.S. is more expensive than moving overseas. I’ve definitely made financially disastrous decisions and I recognize my privilege, but I think the greatest privilege that allowed me to live well abroad was realizing it was possible to do it.

Obviously, growing up surrounded by people who come from other places (not rich people! Just people of different backgrounds) will let you see that life can be lived in places other than the U.S. It’s easier to navigate a system or enter a field when you grow up knowing people who have already done it. Part of the reason it came naturally to me to do illustration is that my mother is an illustrator. I grew up seeing her bent over a drafting table, using an X-Acto knife and an airbrush, pulling all-nighters for deadlines. To me, that was a normal adult job. Only now do I realize how lucky I was to see becoming a professional artist as the most natural thing in the world. But if one has never met anyone who has navigated a particular system, it can make that system seem terribly intimidating.

To me, owning and driving a car is as foreign and scary a prospect as anything imaginable. When I think of a car, I just think “death.” Anything people are scared of—flying, public speaking, eating romaine lettuce—the comforting response is, “It’s not as dangerous as driving,” which just makes me think, “Why are you getting in that fucking car? That’s just death.”

Same! I got my license a few years ago because when Trump was elected, I thought, “Who knows what will happen. It’s ridiculous to live in America and be completely helpless if public transportation goes down.” I learned, but I’m terrible because I’m so scared, all the time, because I am not 16 and I know we’re all in giant, metal death-machines. I am at an age where I know what death is and that it is also something I am subject to.

Molly Crabapple, Ismail Pulled from the Rubble of an American Airstrike, illustration for Brothers of the Gun, 2017.

©MOLLY CRABAPPLE/COURTESY THE ARTIST

People keep saying, “You need to learn to drive, just in case,” but that doesn’t make sense. To have that “in case,” I need access to a car. Plus, I like to walk.

The absolute dependence on a car is really American, because car companies bought up our public-transport systems in many cities and destroyed them, and because our whole infrastructure is designed around cars. So many of us don’t realize there are other ways to be. If so many Americans are provincial, it’s because the powers-that-be foisted this on them and beat it into their heads. “Don’t go abroad. It’s all shit. U.S.A. number one.” If Americans looked at other developed countries, then they would realize we could also have universal healthcare, free college, and high-speed trains—even cities built for us to walk around in.

I am always grateful that my mother, because she is an illustrator, told me to not go to the expensive art school I desperately wanted to attend. She told me, if I got into $100,000 of debt, no matter how good the school was, I would regret it forever. It would trap me. At the time, I was so upset. I thought it was so important that I go to a name-brand school, but she was right. I went to a bad school and I got some scholarships, so it was very cheap. I dropped out of it. I am just glad that I never had debt.

I think most of what’s taught in art schools can be learned in a creative community for free. There is a Trump University aspect to higher education, whatever the field.

It costs what, $200,000, to go to SVA for four years? For $200,000, you can study the masters by traveling around the world and setting up your easel in a museum, or you can pay an amazing painter with classical chops to teach you their secrets.

I don’t believe that you are a real artist if you have assistants paint or sculpt all your work for you. I’m not talking running a studio like Rembrandt, where he did the hard parts and assistants painted the clouds. I’m talking about the way that someone like Mark Kostabi hires broke art-school grads to paint his work for him. If you do that, at best you’re an art director, but more likely you’re just an exploitive CEO. Many fine artists have disagreed with me and said I was a retrograde regressive reactionary, and the real art is in the idea. I don’t buy it. If art is just the idea, you’re saying labor, craft, and work with your hands is contemptible and beneath an artist. No, you have to do your art yourself. With your own hands. If you need other hands too, to make something massive, fine, but your own hands must be there, and doing the hardest parts. I want to make art good enough that people will still want it if society just evaporates and they find my drawings scattered in the wreckage.

[ad_2]

Source link