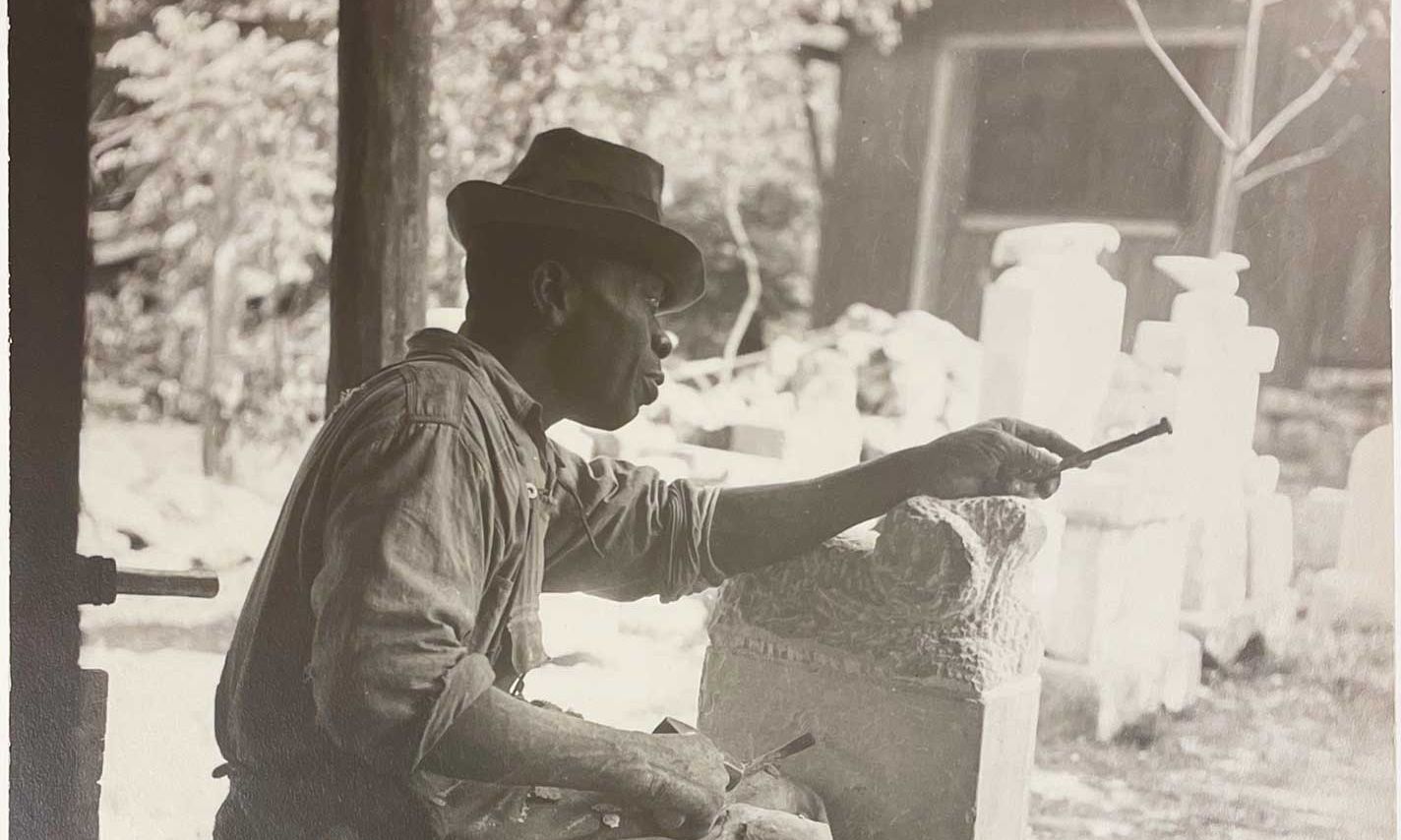

The show at Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation includes Louise Dahl-Wolfe’s 1937 photograph of William Edmondson

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Stone workers in Nashville, Tennessee made frequent deliveries to the house of William Edmondson (1874-1951). Those from the nearby quarry brought him oddly shaped stones that were unusable to builders; others brought leftover pavement stones, selling them to Edmondson to stock his yard-turned-outdoor-studio. There, the self-taught Modernist sculptor inserted his visions into these misshapen blocks, transforming them into angels, animals, tombstones and at least one portrait of the Jim Crow-era heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson.

Now William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision, at Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation, will attempt to carve out a firmer art-historical place for his sculptures. When Edmondson exhibited at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1937 as the first Black artist granted a solo exhibition, he was cast as a naïve and untrained folk artist; this show will honour his unique contributions to Modernism and present his work within the context of his life in Nashville.

Ancient Egyptian Couple (formerly Adam and Eve) (around 1940) by William Edmondson Courtesy of The Museum of Everything, London

More than 60 Edmondson works loaned from institutional and private collections will be on view, including several sculptures from the personal collection of the contemporary artist and folk art collector, KAWS. The exhibition will also include photographs of Edmondson taken by Louise Dahl-Wolfe and Edward Weston in the 1930s and 1940s, the artist’s most active period. To mark the “complex relationship between Black cultural production and the American museum”, according to the organisers, a specially commissioned performance piece by the artist and classically trained dancer Brendan Fernandes will be staged each week in the exhibition space.

Edmondson began his sculpting career carving headstones for Black people interred in segregated cemeteries, at first creating blocky figures resembling the rough rectangular limestone slabs. His style changed over time and by the late 1930s he was carving figures with greater three-dimensionality, in more complex compositions. As Edmondson began attracting the attention of collectors such as Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, he made fewer tombstones and concentrated on more decorative sculptures.

“He channelled his intellectual prowess into the creation of a very different Modernism—inspired by an African American perspective—that was marginalised in his own time and is still slighted today,” writes the art historian Leslie King-Hammond in the exhibition catalogue. “He created imagery that not only advanced the cause of aesthetic excellence, but also recognised and recorded the historical legacy of African American life and religious beliefs in ways that had not been experienced in the mainstream art world.”

Edmondson's Mermaid (1932-41) Collection of Dr. Robert and Katharine Booth

Edmondson carved many animals, such as squirrels, rabbits, lions and rams, and sometimes memorialised public figures such as the US First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. He had “a powerful sense of fantasy,” says the co-curator Nancy Ireson, which he expressed using “an economic sense of line”.

“These here is miracles I can do,” Edmondson was quoted as saying in the 1937 press release for his MoMA exhibition. “Can’t nobody do these but me.”

• William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, 25 June-10 September