[ad_1]

Installation view of Michael Stipe’s “Infinity Mirror” at the Journal Gallery in Brooklyn, with Infinity Mirror (2018) installation in center.

THOMAS MÜLLER/COURTESY THE JOURNAL GALLERY AND THE ARTIST

This interview with Michael Stipe follows up on a previous ARTnews story about Volume 1, a recently published book of visual work by the former R.E.M. frontman and artist, who is now active in many different mediums. The prior story focuses on the book, whereas the discussion below transpired during a walkthrough of Stipe’s exhibition at the Journal Gallery in Brooklyn. Titled “Infinity Mirror,” the show runs through August 19, with works from the book interspersed among other offerings. A sort of centerpiece installation is a large interlocked shelving system on which lay objects and curios collected by Stipe, who has presented them with an autobiographical thrust. Also on view is a section devoted to Jeremy Ayers, an early mentor and friend of Stipe’s from Athens, Georgia, as well as a series of large-scale black-and-white portraits and other book-related images on the walls.

Stipe’s comments below come from our discussion in the space and have been edited and condensed. A slide show with additional images of some of what he talked about follows at the bottom. —Andy Battaglia

SHELVING SYSTEM

Each of these is something coming out of the magic decade of the 1970s. I turned 10 on January 4, 1970, and turned 20 on January 4, 1980, so it was a teenage decade for me. The shelving is ten units designed by Milo Baughman, an American designer. I saw them online and they just looked so ’70s—then I wondered, What would happen if I stacked them? You get that kind of infinity mirror effect where you’re not sure what you’re looking at, where it feels like it’s moving with you. That seemed perfect.

Everything is extremely resonant to me. There are connections to Andy Warhol, Jean Genet, Joan Didion, Louis Armstrong, Patti Smith, Desiderata. And shit lyrics in great songs—that’s from Neil Diamond’s “I Am … I Said,” one of the greatest songs ever written but with one of the worst lyrics: [Singing] “I am I said / to no one there / and no one heard at all / not even the chair.” Not even the chair could hear him scream—that’s a really terrible lyric.

CHAIR ON TOP

I think of that as the only thing outside the very hermetic gesture of this sculpture. It feels like me looking at the impossibility of all of these influences coming through me, and helping form my trajectory and create who I became and who I am. I have a bit of an astonished fan-boy sense still, not quite believing my incredible fortune. That’s embarrassing, but it’s also honest and vulnerable.

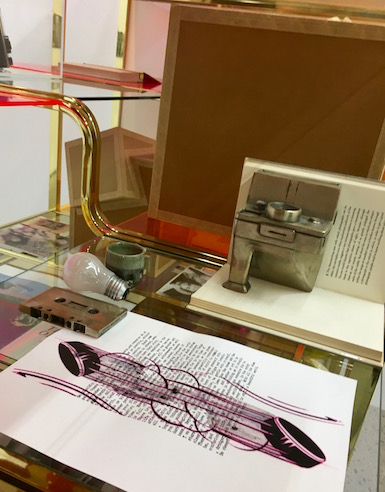

Items in Michael Stipe’s Infinity Mirror.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

LIGHT BULB

This is a very important part of the piece. As a child, I bit into a lightbulb and my father and uncle had to take all the pieces of glass out of my mouth—and glue it back together to make sure I hadn’t swallowed any of it. I was four or five years old. They asked me why I did it, and it was because I wanted to be the filament. I could see the filament inside the lightbulb and I wanted to be that, and the only way for me to get to it was to bite the lightbulb. So I did. It’s really weird. My brain is still trying to process that: I wanted to be the filament inside a lightbulb. That was my intention—I wasn’t trying to get attention; I was embarrassed when they discovered my trying.

PLASTIC BOTTLE

There’s a story as to why it’s in front of the emoji hole [an icon blown up on Escape Hatch Case, an artwork of Stipe’s own that is a hardcover for a book that doesn’t exist] and next to an ad from Evergreen Review, which was Barney Rosset’s from Grove Press. Barney is also on the other side—there’s a signed Samuel Beckett book that came from his personal collection. In the ’70s I took a year-long course in environmental science. It was an important part of that decade, understanding that the generation before us had screwed up the Earth and it was our job to make everything right. We were working toward alternative energy, and environmental science was an important part of my upbringing. The bottle represents that. Also, along with the pink Plexi—the colorful Pop part of this piece—it represents the embrace of all things artificial and plastic in the ’70s, between the utopian ideas of the ’60s and the Me Generation of Reagan and AIDS in the ’80s. The bottle to me represents this unresolved problem that we haven’t yet addressed. We now know that we all have microplastics in our bodies and we’re destroying the oceans. It’s 45 years later and we haven’t done a fucking thing about it. I got the bottle in Venice, which felt perfect to me—a floating city that shouldn’t exist. It’s a swamp basically but turned into one of the most beautiful places on earth.

Michael Stipe at the Journal Gallery.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

FISCHERSPOONER RECORD / FOUND BOOK JOTTINGS

This is a 7-inch record of “Tone Poem” by Fischerspooner, and this [a page with handwriting nearby] was written inside a physics book that Casey Spooner found in Athens in a thrift store. We would sit around trying to read this out loud to each other, and no one ever made it through without cracking up. It’s so absurd. “Where rival ship meets no incentive to impale its reckless course and where all is lulled to peace and quiet is of all places the most appropriate to illuminate the sparkling fires of love and receive in turn the electro-darts of sweet devotion . . .” [Laughs.] This show was almost called “Electro-darts of Sweet Devotion.”

BRUNO SCHULZ BOOK

I read Street of Crocodiles as a young man and fell in love with Bruno Schulz’s writing. This, The Booke of Idolatry, is a really odd book. Years after Schulz became known for Street of Crocodiles, someone found a chest in an attic with drawings of his. He had this incredible foot fetish and did erotic drawings of men bowing down and kissing and licking and cleaning the feet of women.

PYRITE / CARDBOARD MODEL

That’s pyrite, a naturally formed mineral—nothing manmade has been done here except each surface was given a number and then measured and turned into this [a much larger cardboard-replica sculpture]. That’s nature, and this is an ephemeral material—something that’s not precious, that we don’t consider to be important.

CARDBOARD ALARM CLOCK

This is another cardboard replica of the first piece of technology I had that incorporated both analog and digital: it was the first digital alarm clock that played music—you could set it to play a radio station when you woke up. It was part of a “Rogan vs. Stipe” show that happened in a clothing store on Bowery and Bond in 2008. Rogan Gregory was the designer, and it was his store—he opened it up to artists to do installations. We had hundreds of these, filled up in the corner store and spilling out through the window onto the Bowery.

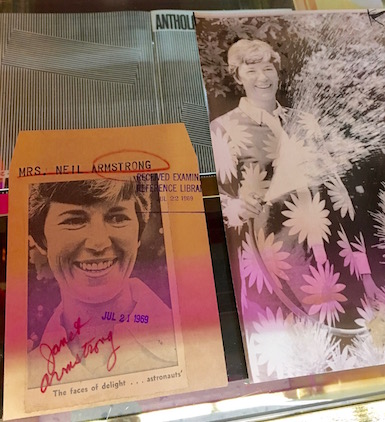

Janet Armstrong in Infinity Mirror.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

PHOTOS OF JANET ARMSTRONG

This is Janet Armstrong, who was always “Mrs. Neil Armstrong,” the wife of the first man to walk on the moon. She was constantly surrounded by a phalanx of photographers and having to present this courageous, grounded, supportive, everything’s-going-to-be-great, it’s-all-going-to-be-fine spirit. Meanwhile her husband’s being shot literally into outer space in a tin can while she’s there with her two children. She to me is an incredible American hero for enduring that. There she is in her sundress with daisies on it watering her garden surrounded by 40 photographers and smiling all the time. She reminds me a lot of my mom in the ’70s. A picture of one time that Janet cracked is in Giants of the Twentieth Century, this artist book I made in 2012 with examples of things that did not make it out of the 20th century and into the 21st: Marlon Brando, the Concorde, the United Nations, the Dewey Decimal System.

COILED ROPE

In the ’70s I would go to the gay bar in East St. Louis with a bunch of people I met around this experimental film theater in St. Louis—I lived ten miles outside St. Louis. The theater once showed Equus and Marat/Sade—two of the most psychologically traumatizing films of all time—on a double bill. Peter Firth in Equus was the first sex scene where I saw a nude, aroused man in a film. He’s a tortured young man who blinds horses, and Richard Burton is the psychologist whose job it is to try to find out why. It’s a really tortured ‘70s film, beautifully acted. Marat/Sade is this play by Peter Weiss that was made into a film, about inmates of an asylum for the mentally ill who would put on plays for wealthy people. This particular play was directed by the Marquis de Sade. It’s really fucked up. Anyway, about the rope: Before we would go dancing at the gay disco in East St. Louis, we would go to this woman’s house who was queer and loved Janice Joplin. We would drink and get naked, and she would tie us up with ropes and take pictures of us. Then we would untie ourselves and get dressed and go disco dancing. Barb was her name. I don’t know whatever happened to those photos.

PROMO STILL FROM THE ELEPHANT MAN

Very few things here are mine from back in the day—most everything is me filling in memories with things I bought or collected. Mike Mills [the bass player for R.E.M.] invited me to dinner once in Los Angeles and we sat at a table with John Hurt. I almost fainted—I was such a fan. The Elephant Man had such a profound influence on me and on R.E.M. Part of my learning how to write lyrics was watching The Elephant Man and listening to the soundtrack. It was of profound, profound importance. I bought this signed promo 8-by-10 glossy online as a fan.

KIMONO SCREEN

This is a Japanese kimono screen for dying silk. The lines are so fine that they hold it together with human hair. This gets into the subject of the next volume of my book, which is going to be about moiré patterns. Moiré is like when you put two mosquito screens together and go like that [moves hands over one another, back and forth], or when you photograph your computer screen or someone else’s iPhone and get rolling lines or patterns that are fucked up. It’s this place where we find ourselves between digital and analog—systems that do not speak to each other and cannot speak to each other without becoming chaotic and damaged and perverted and beautiful, in their own right.

MARCEL DUCHAMP BOOK / PHOTO

When Patti Smith “came back” [in 1995, after years out of the public eye] and Bob Dylan asked her to open for him, I jumped on the bus and followed them around for a couple of weeks and took pictures the whole time. We went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and I photographed The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass). The light is divided because there’s a window behind it with sunlight coming in. You weren’t supposed to take photographs, but I snuck it and wound up putting it in the inside sleeve for New Adventures in Hi-Fi, which became my favorite R.E.M. record. On that same trip to the Philadelphia Museum I saw Brancusi, which was an epiphany. I knew of his work before, of course, but I was like, “What the fuck—I’ve never seen anything like this!” It knocked a hole through me.

Part of a section for Jeremy Ayers.

THOMAS MÜLLER/COURTESY THE JOURNAL GALLERY AND THE ARTIST

JEREMY AYERS TRIBUTE SECTION

An area in the gallery features work by and related to Ayers, who died in 2016 (and Sylva Thin, Ayers’s name while a Warhol superstar in the ’70s)

This is signed on the back by Warhol, a gift to Sylva Thin from Andy. It’s the only remaining picture that Jeremy had in his archive of him and Warhol together. That’s Sylva with Holly Woodlawn en route to John Lennon’s 31st birthday party. And then here’s a letter to Holly—they kept in touch for the rest of their lives. Jeremy didn’t talk about it, but he loved Holly very much. She had a very profound influence on him.

This is Jeremy’s painting called Kyoto Pine. He sequestered himself in Athens for long periods of time. He wouldn’t travel, not even to the coast of Georgia. He would just stay in Athens, but our great friend Kai bought tickets for him to Japan and convinced him to get on a plane. This is the post-Japan Jeremy—he opened up, he became this completely different person who was able to come here and participate in New York again. He came and photographed Occupy Wall Street, with thousands of photographs. He would come up for weeks at a time. He got jobs helping handicapped people, and then in his time off he would wander the streets and find people to photograph, people on the fringe of society. A lot of them were very old people you might walk by a hundred times a day and not even glance at, and Jeremy would stop them and say, “You look incredible. May I take your photo?” That’s a portrait that Jeremy took of me when I was 19 or 20. And that’s one I took of him. This record was the soundtrack of our short affair: Einstein on the Beach.

Installation view of “Infinity Mirror.”

THOMAS MÜLLER/COURTESY THE JOURNAL GALLERY AND THE ARTIST

BLACK & WHITE PORTRAITS BY STIPE

The show is taking from the book and expanding outward, using it as a center. In the book are two images of guys who have been painted, and this is other work I did during that period. I started painting them because some had tattoos—I wanted to do a classic study of the human form, so I painted over them so there wouldn’t be more information than just the body. I wound up with these beautiful patterns that reference all kinds of other things. That’s like Malevich [points to black square]. And then there were movements where people painted themselves and did all kinds of really violent things, very destructive. I acknowledge chaos, but I don’t tend to want to spotlight it.

This series for me was about going back to me starting as a teenager working with photography and projecting backward. What would I have wanted to do then? I would have wanted to ask men to model nude for me and photograph them and do something beautiful. That’s why I shot on Tri-X, the classic Kodak black-and-white film. It’s 400 ASA, so it’s easy to use if you’re not completely knowledgeable about the mechanics of a camera. It’s very forgiving. And when you blow the pictures up this big you get this insane grain. These are from Xeroxes that we printed out at Kinko’s. When you see them in person, you get that thing where you back up and see it with greater focus. When you hold up your phone take a digital image of this giant analog print, it becomes more sharp. The camera is lying to you about what this is, which is kind of beautiful.

-

The Venetian plastic bottle and the emoji hole.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

-

A cardboard replica of pyrite.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

-

A tribute to an alarm clock of yesteryear.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

-

The signature of the great Samuel Beckett.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

-

A book made in a small edition.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

-

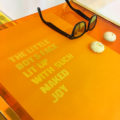

Lyrics by Patti Smith next to glasses and petrified sea urchins.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

-

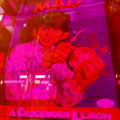

Mad magazine signed by Malcolm McDowell.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

-

A book that belonged to Jeremy Ayers.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

[ad_2]

Source link