[ad_1]

Architecture critics are not, as a rule, individuals of uncompromising scruple. This isn’t so much a character judgment as a statement of professional fact. Since architecture lacks anything like true artistic autonomy—constructing a significant building requires capital and capital “P” Power—its critics are always a little wrong-footed, always in danger of amplifying the discipline’s intrinsic flaws. If, as Philip Johnson famously declared, architects are “pretty much high-class whores,” then what does that make the people who write about them? Perhaps little more than maquereaux hawking them to the public.

While most of us have come to terms with our fallen condition, Michael Sorkin, who died last month of COVID-19, fought it tooth and nail. Sorkin, in fact, would have objected to much of the above argument, especially to the mention of Philip Johnson. In his writings, he defended both architecture and the role of the critic in terms that swung from barbed invective to teasing satire, from the theoretical to the personal, and that in no way spared the feelings of his fellow design writers. In a scathing review of New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger’s 1981 book The Skyscraper, Sorkin excoriated the author and others of his stripe as standing “in the same relation to their subjects as advertisers do to their products,” while insisting that critics should answer to a higher calling. As he put it in another piece, “a critic’s torpedo must home on power and its symbols.”

Sorkin was the Village Voice’s architecture critic in the 1980s, and during his tenure there he took up the lance of progressive modernism against the revanchist Postmodernist tide (a “cloddish neo-con reaction,” in Sorkin’s words) and its financier enablers. That same decade, he founded the socially minded architecture practice Michael Sorkin Studio, later followed by its research and publishing offshoots Terreform and Urban Research, respectively. More recently, he was the architecture critic for the Nation and a professor at the City College of New York. Through it all he authored numerous books, lectured widely, and participated in countless endeavors as an activist, as comfortable with the bullhorn as with pen or pencil.

Courtesy Michael Sorkin Studio.

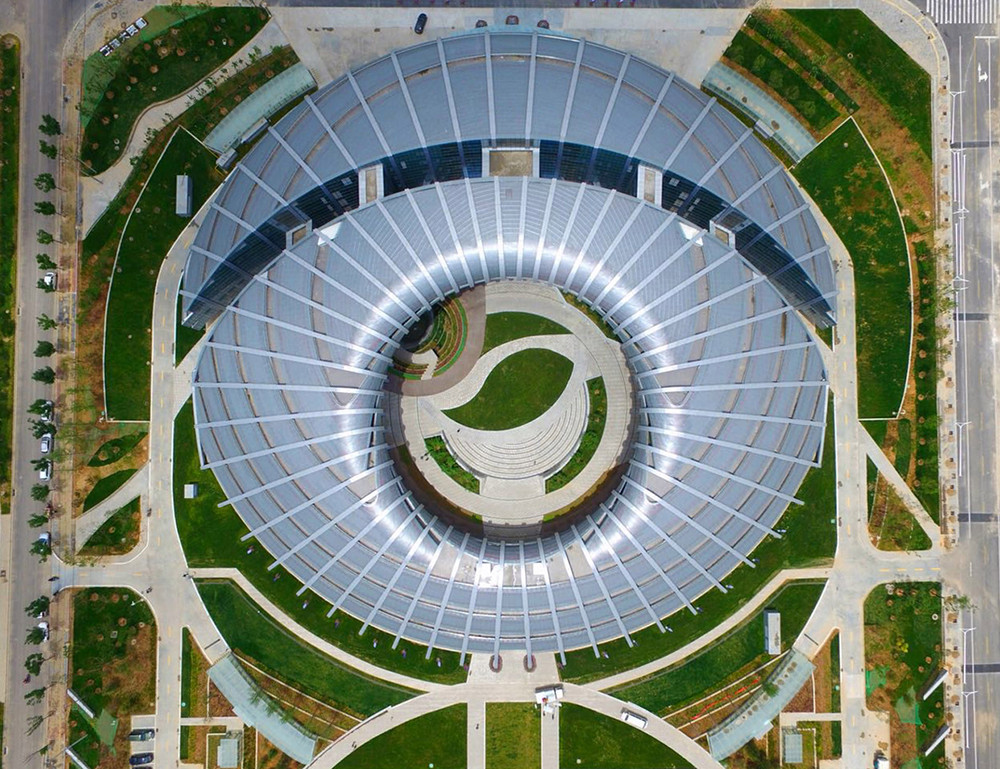

In 2015, when Finnish architecture students started agitating against a proposed Helsinki branch of the Guggenheim Museum, which would use public funds to benefit an American institution, Sorkin was there, lending his insight and organizational acumen. (Successfully, too: the project never moved forward.) In 2016, when the CEO of the American Institute of Architects voiced the organization’s willingness to work with the incoming Trump administration, Sorkin was there again, lambasting the AIA and swearing “to revile and oppose” what he deemed the “nativist, sexist, and racist political project” of the new president. As a practitioner, Sorkin created designs—from speculative urban-farming schemes for Chicago, to realized work like a curvaceous, lushly landscaped airport service center in China—that were statements in themselves, brimming with ecofuturist ambition. Political engagement was the connective tissue of Sorkin’s entire career, the impetus behind his buildings as much as his books.

That he excelled as both an architect and a writer—he held graduate degrees in both architecture and English literature—is in itself extraordinary, and not a little confounding. Lyrical, verging at times on the experimental, his writing was of such a high caliber that it would be nice—comforting, maybe—to assume that it was his exclusive focus. A bullet-pointed disquisition, “Two Hundred Fifty Things an Architect Should Know” (2015) includes such gems as “the quality of light passing through ice” and “dawn breaking after a bender”; a 1989 essay on the Italian architect Gaetano Pesce is presented as a series of footnotes to an “absent” text. In a profile of Emilio Ambasz included in his 1991 essay collection Exquisite Corpse, Sorkin described one of the designer’s landscape drawings as “animated by squiggly lines and a spray of tiny tempietti.” When he was on a proper tear, Sorkin’s poetry and his politics would begin to run together, connecting a building’s form to violence half a world away. Discussing architect Richard Rogers’s techno-glam headquarters for the insurance brokerage Lloyd’s of London (completed in 1986, at the height of the Iran-Iraq War), Sorkin wrote that “Lloyd’s offers, in lieu of chiseled aphorisms, the flickering incitement of prices flashed on robot television screens, not to mention the sonorous tollings of the Lutine Bell every time an Exocet hits pay-dirt in the Gulf.”

But the intrigue of Sorkin’s all-encompassing commitment goes further than just stylistic élan. The general prejudice in architectural circles has it that critics are critics, designers are designers, and never the twain shall meet. For the latter party, the crushing demands of the studio make it largely a matter of manhours, but for critics the rationale is more involved. “There are no more utopias,” declared influential theorist Manfredo Tafuri, in 1986, adding that “the architecture of commitment, which tried to engage us politically and socially, is finished.” By Tafuri’s account, design was so hopelessly compromised by capital as to be beyond rehabilitation. For the critic, the only respectable position was therefore one of detachment—objective, skeptical, politically conscious but solely in the negative sense in order to abjure the pitfalls of engagé optimism or what Tafuri termed “operative history,” the enlistment of the architectural past in service of a future architecture. The net result of Tafuri’s influence has been a pervasive distaste in the critical community for indulging utopian fantasies(to say nothing of participating in them), and most of us, whatever our commitments, dwell at least somewhat in the shadow of this prejudice: anxious not to sully ourselves with practice’s dusty mixture of gypsum and compromise, and hesitant to advance a cogent vision of the future.

Courtesy Michael Sorkin Studio.

Not Sorkin. In an online remembrance, one of his former students, Rodolfo Leyton, relates how Sorkin encouraged him not to dwell on professional or historical particulars, but rather to ask himself “how are we going to struggle together to make a new, bright, responsible future?” Actuated by the firm belief that such a future was within the capacity of architects to create, Sorkin sallied forth, a one-man rescue mission for both utopianism in architecture as well as the “operative” critical project. Whether skewering power-mongers—as in his self-described “Philippics” against the aging Philip Johnson, whose past as a Nazi sympathizer Sorkin gleefully exposed in Spy magazine—or dreaming up sustainable garden-topped towers, Sorkin set a standard for moral conviction that few critics could hope to aspire to, and fewer still attain. His absence at a moment of such acute economic, social, and political crisis seems especially cruel, not the least given its cause, a virus whose spread has been abetted by the very administration that Sorkin so loathed. For those of us of more timid dispositions, the most apt words are Sorkin’s own: reflecting on the artist Gordon Matta-Clark, whose death arrived just as his work was becoming most relevant, Sorkin wrote: “We sure could use him now.”

[ad_2]

Source link