The Memphis Sanitation Strike occurred between February 12 and April 16, 1968. The sanitation strike was called in response to the deaths of sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker and in response to the racial discrimination that Black sanitation workers experienced. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, who was organizing the Poor People’s Campaign at the time, came to Memphis to support the sanitation workers. His presence led to his assassination on April 4, 1968.

On February 1, 1968, two Memphis garbage collectors, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning garbage compactor truck where they were taking shelter from the rain. On February 12, 1968, around 1,300 Black men from the Memphis Department of Public Works went on strike. T.O. Jones, a garbage collector turned union organizer, led the Sanitation Workers. They were supported by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). The main goal of the strike was to demand recognition of the union, better safety standards, and a decent wage.

On February 22, 1968, the Memphis City Council voted to recognize the union and recommended a wage increase. Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb, however, rejected the vote, insisting that only he had the authority to recognize the union. He refused to do so. On February 24, 1968, Rev. James Lawson led a meeting at Clayborn Temple Church, which created a local civil rights organization, Community on the Move for Equality (COME), to support the sanitation workers.

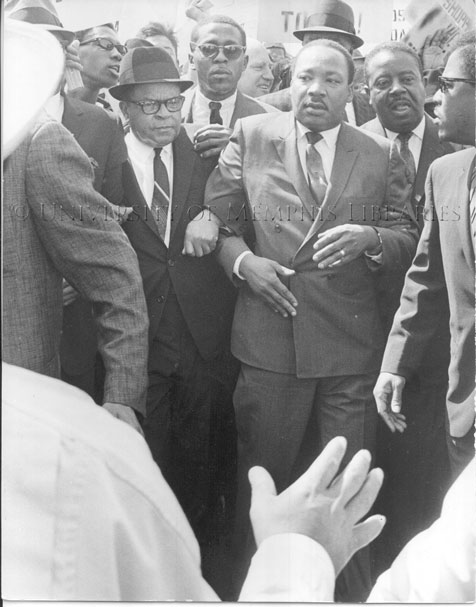

In March, Lawson invited Dr. King to come to Memphis to speak to sanitation workers. Other civil rights leaders, including Roy Wilkins and Bayard Rustin, came to Memphis to support the sanitation workers. On March 18, 1968, King arrived and spoke to 25,000 people at Mason Temple, a prominent Memphis Church. King encouraged the crowd to support the sanitation strike by enacting a citywide work stoppage. He also promised to return to Memphis on March 22 to lead a protest through the city.

The following day, King left Memphis, but SCLC members James Bevel and Ralph Abernathy remained in the town to help organize the protest and work stoppage. On March 22, a massive snowstorm hit Memphis, causing King to cancel his return to the city and local organizers to reschedule the march for March 28. On that day, King and Lawson planned to lead the sanitation strikers and marchers through downtown Memphis. City officials estimated that 22,000 students skipped school to participate in the march. King arrived late and found the crowd on the brink of chaos. He quickly called off the demonstration as violence began to erupt, and he was taken to a nearby hotel for his own safety. During the violence, police officer Leslie Dean Jones shot and killed 16-year-old Larry Payne. In response, Mayor Loeb declared martial law and brought in 4,000 National Guard troops to calm the violence.

On April 2, 1968, around 600 people attended Payne’s funeral at Clayborn Temple. The following day, King returned to Memphis a third time to visit Payne’s mother. The next day, King gave what would be his final speech at the Mason Temple, I’ve Been to the Mountain Top. On April 4, 1968, King was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel. Following King’s assassination, the city of Memphis recognized the AFSCME, and wages were increased for the sanitation workers.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

“Memphis Sanitation Strike,” The Martin Luther King Jr Research and Education Institute, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/memphis-sanitation-workers-strike; “Memphis Sanitation Strike,” Civil Rights Digital Library, https://crdl.usg.edu/events/memphis_sanitation_strike/; Michael K. Honey, Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008).

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.