[ad_1]

When Jeffrey Wright arrived back on set six months after shooting the pilot for HBO’s sci-fi series “Westworld,” he came armed with a heavy secret.

He’d recently learned that his character Bernard Lowe, the reserved head of Westworld’s programming division and guardian of all robots contained within the futuristic Wild-West amusement park, was an android. Like the subjects he’d be monitoring throughout the series’ first season, Bernard was not, in fact, as human as fans had been led to believe. Rather, he’d been designed by Westworld mastermind Dr. Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins) and modeled to appear like his late business partner, Arnold Weber.

This colorful secret informed every morsel of Wright’s performance in Season 1, unbeknownst to his colleagues. In an early scene with Evan Rachel Wood, who plays Westworld’s oldest robotic host, Dolores Abernathy, for example, a suited-up Wright calmly asks her, “Do you remember our last conversation, Dolores?” She looks at him sweetly, responding, “Yes, of course.” At the time, Wood assumed this was a typical programming exchange between her character and Bernard. By the end of the season, however, the actress realized she’d been acting across multiple timelines ― that Wright had at times been playing Bernard and at other times Arnold. Slight shifts in Wright’s personality and wardrobe, and each scene’s setting, artfully camouflaged the reveal.

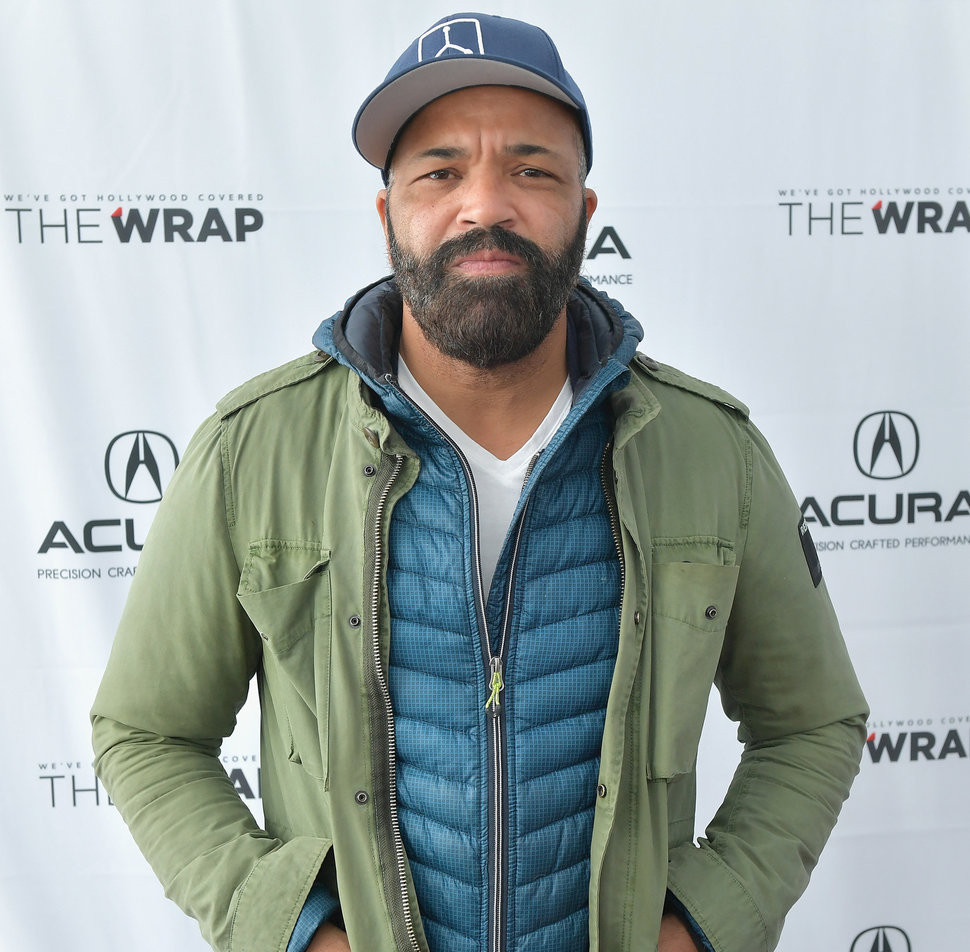

“No one knew until they got the script of the seventh episode, and then texts were flying my way,” a bearded Wright told me during the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, earlier this year. “People had their wigs blown off that I held this from them for the many months that we were working on it.”

“I texted him, ’You! You! How did you do that? How did you keep that from everyone?’” co-star Luke Hemsworth, who plays security officer Ashley Stubbs, expressively told me. “There are all these little cookies and Easter eggs where you go, ‘Oh, that’s what that is’ or ‘That’s why Jeffrey’s doing that!’ … There’s not a gesture or an eye movement that doesn’t make sense when you go back and watch it again.”

“I’d been working with Jeffrey for half a season and I find this out, and I’m like, ‘Did you know?!’” Wood reiterated. “You find out these people who you love, who you work with every day, are holding these secrets from you!”

Jeffrey has this real intensity… And he’s not putting it on. He doesn’t come in with a whole lot of need, which is really, I don’t know, it’s kind of hot.

Mary-Louise Parker

Wright is good at stoking mystery. Before I met him, I associated the actor with the broody, bookish characters he’s played on TV and film ― like Bernard, who lives in suit vests and laboratories. On the day of our interview, Wright was nothing like Bernard. He was dressed casually in a baseball cap and unzipped jacket, puffing from a vape pen in between laughs. We’d just escaped the snow-covered sidewalks of Park City and landed comfortably inside a pop-up vodka lounge, where he was smirking at the thought of his colleagues’ “Bernarnold” ignorance. As we sat across from each other, he took his time crafting answers to my questions, hitting each beat with a sort of temperate ease.

Off-screen, it was easy to see why he’s HBO’s go-to guy, the kind of player who can pop in and out of any thematic narrative, molding himself into an array of dense supporting characters.

“Westworld” is Wright’s sixth project with the premium cable juggernaut, which has become the artist’s de facto television home. He first appeared on the network as Martin Luther King Jr. in 2002’s “Boycott,” which won a Peabody Award “for refusing to allow history to slip into the past.” Since then, HBO has refused to let Wright out of its clutches. Over the past 16 years, he’s starred in the “Angels in America” adaptation (2003), the R&B-fueled “Lackawanna Blues” (2005), the Prohibition-era drama series “Boardwalk Empire” (2013) and the Anita Hill biopic “Confirmation” (2016).

“He’s a world-class actor,” HBO Programming Chief Casey Bloys said. “Just on our network alone he’s played MLK, he’s played a gangster and he’s played an empathetic robot. I don’t know many actors who would be able to pull that range, not only of characters but also of tones of shows and movies. He brings this depth and humanity to his characters, and I think that’s why we continue to go back to him and why he’s so in demand.”

Now he’s the glue holding “Westworld” together. And maybe, after all this time, HBO, too. On screen, Wright is the kind of performer who captures your gaze the minute he enters a frame, his deep, gravelly voice entrancing viewers into a meditative-like state. His affectations are subtle yet deliberate, like the creaking of an old wooden floor in a suspenseful thriller. Wright is, as Bloys and others have said, a first-rate actor.

“Jeffrey has this real intensity,” his “Angels in America” co-star Mary-Louise Parker told me. “I have not talked to him about it, but I feel like it’s largely inspired by his intellect. And he’s not putting it on. He doesn’t come in with a whole lot of need, which is really,” Parker paused, gathering her words, “I don’t know, it’s kind of hot,” she giggled over the phone.

“He’s a super sexy guy, obviously, but you don’t feel like he needs a lot from you, and he doesn’t. He doesn’t. But he has a bucket-load to offer both from his life experience and from his ideas.”

That sex appeal might be hard to comprehend if you’re a fan of the Jeffrey Wright who’s played Bill Murray’s mystery-obsessed neighbor in “Broken Flowers,” electricity wiz Beetee in “The Hunger Games” franchise or Bond’s CIA operative pal Felix Leiter in “Casino Royale” and “Quantum of Solace.” The beauty of Wright, though, is his chameleon-like qualities, which allow him to be cast as a nerd in one project and a well-worn prison inmate in another. It’s why, according to him, Wright no longer auditions for parts.

“I look at it this way: I’ve been doing this for 30 years now. If a director can’t figure out what they might get from me or whether he or she wants to work with me based on what I’ve done, then I can’t tell them anything more than what they don’t know already.”

Another thing I learned about Wright during our Park City encounter: He’s a certified jock. He played lacrosse in college (there’s even a U.S. Lacrosse Magazine story to his name), surfs often (with a Hemsworth brother, no less) and does what most celebrities are too busy red-carpeting to do: skis when he’s in Utah.

“I skied yesterday,” he told me, “with a woman who lives out here who’s a stunt woman on ‘Westworld’ … she dragged me across the mountain like a rag doll.” Wright went on to bemoan his 52-year-old knee and praise his ski partner’s ability to eviscerate the slopes, but a quick glance at Wright’s Instagram proves his deprecation is another element of illusion.

“It was a big surprise to me that he surfed,” Luke Hemsworth said, “but then I got to know him and learned he used to be a big skater. He’s like a 12-year-old grommet when he’s in the surf. He’s so amped and wants to go surfing every single day, whether it’s big, small, wind sideways ― it’s an infectious energy.”

Wright was at Sundance for the premiere of his film “Monster,” in which he plays the father of a teen named Steve Harmon (Kelvin Harrison Jr.), who’s wrongfully accused of a deadly crime in a Harlem bodega. The film immediately hit home for Wright, “as the father of a 16-year-old brown-skinned boy in New York City, in America.” The actor, whom Parker calls “a great father,” has two children with his ex-wife, British actress Carmen Ejogo ― son Elijah and daughter Juno. Their home base is Brooklyn, New York.

“When we shot the film, there was what seemed like a much more productive conversation around policing and police-community relationships or justice reform or bipartisan conversation, so it was timely. But I think it’s even more urgent now, because that conversation has been overshadowed by retrogressive political thinking and action, particularly through the [Department of Justice] and the attorney general,” he said.

Wright is comfortable speaking about the current administration. He grew up in Washington, D.C., in the 1960s and ’70s with a mother who served as a lawyer for U.S. customs for 30-plus years. (His father died when Wright was a young child.)

“Her responsibility at headquarters was processing and assigning penalties to certain cases. If I’m not mistaken, she actually was the first black woman and second or third overall woman working for the U.S. Customs Service,” Wright explained during a phone call earlier this month. He happened to be with his mother at the time of our follow-up chat.

He spent many hours in the hallways of her office, he recalled, doing homework and waiting for her shift to end. He became familiar with the inner workings of a government, one that he said functioned far differently than the oft-lambasted administration of today.

“The conversation around the nature of those who work in government has been so poisoned of late by bad-acting politicians who are actually the ones who are far more likely to be corrupt and corrupted than those who make it their life’s work to serve the government of the United States,” he explained. “I’m not saying that across the board, but it was my experience growing up.”

I grew up in that world of professionals and politically oriented folk, and so when I started acting it was really kind of a departure from what I had vaguely perceived my future to be.

Jeffrey Wright

Wright was a staunch supporter of Barack Obama, and he campaigned for Hillary Clinton in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election. So one doesn’t have to assume what he and his mother think of the current president.

“I can tell you this, having been in law enforcement and within the federal government for all those years, [my mom’s] antennas have been up for many, many months,” he stated. “The more we learn, the more, in my case, it seems Mom is often right.”

For a long time, Wright assumed he’d venture into politics, too. Theater, however, became a childhood fixation more interesting than the outside of his mom’s office.

“My mom used to take me to the theater to see the tours that would come through D.C., and I loved it. I loved it,” Wright remembered. “I was absolutely enthralled by the theater and by that world.

“I think that informed me later, but I was afraid, in some ways, to act on it until it was too late and I couldn’t resist anymore.”

At Amherst College, Wright majored in political science and organized rallies against apartheid in South Africa. But by his third year, he’d joined a theater group. After graduating with his bachelor’s degree, Wright earned a scholarship to attend the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. He dropped out after two months, but not for lack of interest. He simply realized he didn’t need a teacher to tell him what he already knew.

“I took a class in college… I think we were reading some short Chekhov plays, and I knew the first day of the class that I was going to be an actor. It was just the bizarrest thing, but it just felt like home.”

![<strong>“</strong>I was honored to be working with [Wright],” "Angels in America" co-star Mary-Louise Parker said](https://newsonmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/1524322192_446_meeting-mr-wright-huffpost.jpeg)

The project that would become the spur of Wright’s career landed in his lap a few years later. After working in theater “to build an understanding of the craft,” he was cast in the 1993 stage production of Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Angels in America” as charming nurse Norman “Belize” Arriaga and Mr. Lies. Wright seared onstage. Even then, he knew it was a role that would change the course of his life.

“It was the ideal work for me. It was the work that I think I aspire to do and that was work that was timely and smart, that was topical and fierce, and deeply, unabashedly political. So it was the merger of these two seemingly competing interests that I’d had growing up: theater and politics.

“It was also pretty damn good,” he added with a laugh.

The complex, allegorical show about AIDS and gay culture in America during the Reagan administration is back on Broadway today, with stars Andrew Garfield, Nathan Lane, Denise Gough and Nathan Stewart-Jarrett, among others. Wright has yet to see it, but he’s looking forward to catching the two-part production in a different light.

“I perceived the play, up until very recently, as being almost archival,” he said. “But it has perhaps as great a resonance now as it did 25 years ago when we first performed it on Broadway, and that speaks to two things: It speaks to the power of Tony’s writing and his mind, but it also speaks to the unfortunate nature of the political climate that we currently find ourselves in.”

Although Wright remains unaware of any criticism lobbed at the play back in ’93, he understood even then that the subject matter could incite opposition.

“As far as the politics [of the play] go, yeah, I’m sure there were some conservatives on the right who took issue with it. I hope they did, because it was definitely right to the jaw of the complacency and absence of empathy that the Reagan administration and conservatives applied to his response to Americans who were dying at an alarming rate from this horrible disease,” he said.

“What I remember is being onstage at the curtain call, taking a bow with my fellow cast mates and feeling this response from people in the audience. I remember clearly on many nights standing there and thinking to myself that I was exactly where I was supposed to be in my life … and it was perfection. So, any criticism, any resistance meant nothing to me because we were doing what we were to be doing, and I didn’t give a shit what anybody had to say about it. “

As an adult, and certainly as an artist, the cornerstone for me is ‘Angels in America.’ It shaped and reshaped me to my core. Everything that I do as an actor, I do relative to that piece and to that experience.

Jeffrey Wright

Wright went on to win the Tony Award for Best Supporting Actor in a Play and in 2003 reprised the role of Belize in Mike Nichols’ HBO adaptation. The HBO show, co-starring Parker, Meryl Streep, Al Pacino, Patrick Wilson and Emma Thompson, earned Wright an Emmy for Best Supporting Actor.

The miniseries aired a year before Bloys joined HBO, first as the director of development for independent productions. “It’s one of the reasons why I and a lot of people wanted to work here,” Bloys said of Wright’s performance in “Angels in America,” to be a part of “that sort of groundbreaking television.”

“When I think back on the work that I’ve been able to do and the work in my career of the highest quality, a huge portion of that has been on HBO,” Wright told me. “That didn’t happen by accident.”

No, it makes sense. The type of acting he sought to do ― “timely and smart … topical and fierce … deeply, unabashedly political” ― required the kind of high-altitude budget and cable chutzpah HBO was willing to throw behind projects. But HBO profited, too. When it came time to cast recent tentpole programming ― first the lavish period piece “Boardwalk Empire” and then the hopeful “Game of Thrones” replacement, “Westworld” ― the network turned to one of its most valuable players. If anyone was going to carry the wildly expensive, $100 million series to success, it’d be Wright.

And the actor was eager to do it. He’d keep the show’s secrets in exchange for the opportunity to work alongside Wood, Hopkins and Thandie Newton. “It’s,” he paused, inhaling his e-cigarette, “deeply gratifying stuff…. It’s grueling, brutal. It’s intensely challenging, complicated but alive and fresh, and exists on the horizon of things that I have done in the past. So it’s really where I want to be right now.”

Back in January, Wright had just wrapped the “seriously ambitious” six-month shoot for “Westworld” Season 2, which he said was equivalent to filming six feature-length films. The days were long, the content intricate and the schedule unrelenting. At times, he said, the production team had four units shooting at once (“on average we have two units shooting at once”), barrelling their way through 15- and 16-hour days (“sometimes 19- to 20-hour days”).

“We’re really trying to expand what’s possible in this type of storytelling, doing it on a scale that’s epic and all on film,” Wright said. “If anyone has the impression that it’s a luxurious, glamorous process that goes into putting these things together, they’re wildly mistaken.”

The show’s subject matter alone would scare some performers off. Here we have a futuristic theme park that functions as a source of expensive entertainment for guests who want to escape the real world and perhaps kill, befriend or romance a couple of robots ― robots who are reaching levels of self-realization. There are graphic shootouts, metaphorical mindfucks, and, of course, HBO’s typical quota of nudity. It’s thrilling yet complicated, confusing yet enlightening.

Wood describes “Westworld” as “intense and violent” but capable of displaying these “incredible moments of humanity.” It’s those moments of humanity ― the show’s ability to be a “meditation on many things” ― that keep Wright coming back. In fact, according to Wood, Wright describes their scenes as “dual meditation,” in which they embrace the rhythm and the tone of the content ― content that, if he had to distill it down to its essence, is about “personal self-examination. It’s about personal awareness. It’s about our relationship to freedom or to restriction.”

Season 2 will certainly tackle this idea of freedom and what it means to discover your personal potential. When we last left Westworld, the robots had revolted and were out for blood. In new episodes, Bernard continues to struggle with his dual identity while Dolores rallies her fellow androids for revolution. As Wood explained, “I had some [secrets] of my own this season, and the tables have turned for Jeffrey.”

“In some ways, the first season was really the table of contents — you understand who, what, where, when, when and when,” Wright said. “But the second season makes the first season look like a kitchen drama,” he added, letting out a hearty laugh.

The best scenarios for me are those in which it’s solely about what’s on the page on the script and about the collaborators involved. It just so happens that HBO has provided a lot of those situations for me and for many actors.

Jeffrey Wright

Don’t be fooled: There’s much more to Wright than prestige TV. This year, in possibly his first leading film role since playing American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1996’s “Basquiat,” Wright stars in “O.G.” as maximum-security inmate Louis, who, 24 years after committing a violent crime as a young man, finds himself on the cusp of release. His involvement with a new prisoner weeks before his departure, however, stirs up some unneeded trouble for the remorseful offender.

The film, directed by Madeleine Sackler, will make its debut at this month’s Tribeca Film Festival. Wright is also set to appear in the highly anticipated film adaptation of Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch as Hobie alongside the likes of Nicole Kidman, Ansel Elgort, Luke Wilson and Sarah Paulson. (The John Crowley movie is expected to be released in October 2019.) Although he’s extremely comfortable as an ensemble character at the top of HBO’s roster, his star-turning role on “Westworld” has certainly opened new doors for Wright, doors he can’t even believe ever opened.

“I remember I used to imagine the world beyond the stage – backstage ― in my little 7- or 8-year-old head,” Wright said. “Now, I realize I’ve been working as an actor for 30 years …. It’s gratifying stuff.”

[ad_2]

Source link