[ad_1]

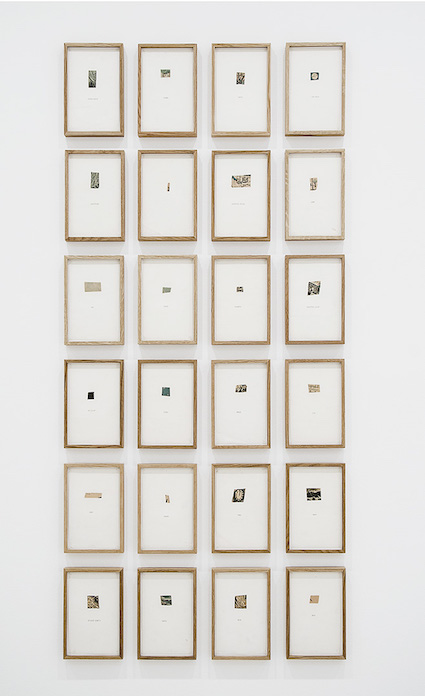

Installation view of “Matt Mullican: Organizing the World,” 2011, at Haus der Kunst, Munich.

JENS WEBER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MAI 36 GALERIE, ZURICH

Known for his vast installations and sculptures about signs, symbols, and the way they produce meaning in a world saturated with images, Matt Mullican is currently the subject of a retrospective at the Pirelli HangarBicocca museum in Milan. With that show in mind, republished below is Peter Clothier’s profile of Mullican, which first ran in the Summer 1989 issue of ARTnews. The article focuses on the artist as he readies a large-scale project that involved using computers to create networks of symbols. “I like that idea—an engine generating meaning,” Mullican told Clother. The article, reprinted with the permission of the author, follows in full below. —Alex Greenberger

“Sign Language”

By Peter Clothier

Summer 1989

For Matt Mullican the world is made up of signs with variable meanings. The “City”—his model of human knowledge and experience—is a sign of artistic maturity

‘I’m not very articulate today,” Matt Mullican apologizes over a hasty cup of coffee at a small café near the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. The high rises of the still-developing Bunker Hill area loom above: labyrinthine steel and concrete corridors reach out into shadowy distances, recalling Mullican’s own mythic “City”—lately the focus of almost all his work. “I’m flying out on the red-eye,” he says, “back to New York. When I get back, I have an opening at Michael Klein, and another show opening in Lucerne, Switzerland, two weeks after that.”

Matt Mullican.

PETER BARACCHI/COURTESY MAI 36 GALERIE, ZURICH

At 37 Mullican has established a restrained, solid reputation for work whose central image is the sign. His highly stylized, logolike notations, often enclosed in simple circles, range in reference from the familiar international airport and highway insignia for necessities like food and rest rooms to recurrent personal designs invoking such universal abstractions as subjectivities, God, and death. Deployed in forms as diverse as posters, banners, stained glass, stone, and rubbings on canvas, their insistent, enigmatic presence among other occupants of the world of signs seems to challenge interpretation even from the casual observer. And thanks to recent large-scale public projects, they are becoming as familiar on city streets throughout the United States and Europe as in such museums and private collections as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Frederick R. Weisman Foundation.

The artist’s larger public commissions can command up to $150,000. For all the seemingly cool hermeticism of his work, Mullican has developed a wide appeal, perhaps in part because of the quiet depth of his conviction and the visual directness of his statement in an art world that is often ironic, self-promoting, and shrill. Ned Rifkin, chief curator for exhibitions at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., describes Mullican as “unique among his generation. Unlike some others who get into the whole business of the art-world positioning, he has a lot of soul, a lot of touch. He’s a highly ethical artist, very straight-ahead, yet very much wrapped up in what he’s doing. He’s constantly processing ideas.”

The description seems accurate when one meets the artist, who is soft-spoken and introspective yet disarmingly direct. Mullican works out of New York in a co-op loft in Little Italy and shares a SoHo apartment with his wife, Valerie Smith. (The former curator of Artists Space, she is currently embarked on a doctoral program in art history at City University of New York.) “Especially in the past four years or so, we’ve had no time for anything besides work,” he says. In L.A. for a weekend to work on plans for a complex supercomputer project, the results of which will be installed in the Museum of Modern Art’s Projects Room this summer, Mullican could grab only an hour to stop and talk about this and other current preoccupations, which have him traveling in a single month to Belgium, Ireland, Canada, Portugal, and Provincetown, Massachusetts, in addition to Switzerland.

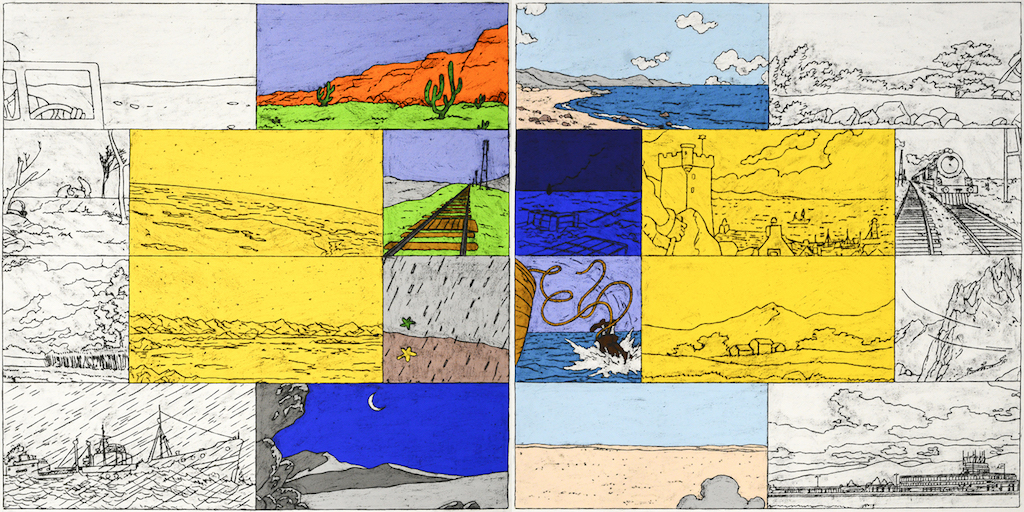

Matt Mullican, Untitled Details From a Fictional Reality, 1973. Installation view, Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, 2013.

DANIEL URIBE/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MAI 36 GALERIE, ZURICH

This particular trip is homecoming as well as business for Mullican, who moved from southern California to New York in the early 1970s. Born in 1951, he was raised in Santa Monica, the son of two painter, Lee Mullican and his Venezuelan wife, Luchita Hurtado. Art was a governing factor in Mullican’s life from his earliest years. As a child he’d be given, along with the usual toys, rolls of butcher’s paper and black paint. “It’s no wonder that I hate to paint today,” he says, laughing good-naturedly. “I had enough painting with my parents. My God, I smelled oil all my life.” Not that he lacked aspirations. “I had to make my own person,” Mullican explains. “My last year in high school, I was already doing performances. I was doing conceptual work when I was twenty years old.”

At the beginning of the ’70s, California Institute of the Arts seemed like the obvious choice for a student of Mullican’s inclinations. A school that at the time was still in its own rebellious infancy, CalArts demanded only that its students think and act like artists. “It was like graduate school for undergraduates,” Mullican says. In a sink-or swim education environment, Mullican was a swimmer—along with such classmates as Jack Goldstein, Troy Brauntuch, David Salle, James Welling, and Ross Bleckner, and with the help of faculty like John Baldessari, whose teaching and example led a generation of students beyond the horizons of then-accepted art.

“I still have tremendous respect for the artist we learned from,” says Mullican. “People like Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Beuys, Bruce Nauman. But I felt that the more reductivist aspect of Conceptual art as a supposedly objective investigation had exhausted itself. Art had been defined objectively down to its essentials, and I wanted to deal not with the object so much as the subject—that is to say, what we bring to the object.” The work Mullican did as a CalArts student had to do with the way an object is perceived not as objective physical evidence in itself but by the light that it reflects. He would, for example, train a green light on an ordinary color cue card, “to show that color was not a constant. But then, if all I see is light patterns, where does meaning occur? Obviously, it exists within me.”

This notion led directly to the stick figures that populated Mullican’s early post-student work. The jump was a simple conceptual one: “Again, if what I see is light patterns, what’s the difference between a stick figure and an actual figure?” Drawing on the culture that surrounded him, he found ample confirmation that the stick figures whose lives he began to construct and, in performance, to narrate, were no less real than the fictional light constructs of, say, television. “I proposed that the stick figure lived in actual life. You could say I took the idea to an absurd length—and it felt like a good thing to do, given the state of the media, where people’s lives revolve around the fictional images of soap opera. I was just trying to find the level of the fictional image, which was subjective.”

Mullican first arrived in New York in 1973 on an exchange program between CalArts and Cooper Union. A young artist of freely admitted ambition surrounded by others equally hungry to make a mark, he took advantage of the city’s rapid response to new ideas, showing and performing through the end of the ’70s in artists’ collectives or alternative spaces like The Kitchen or Artists Space. Fellow artists, including David Salle, Ross Bleckner, and, above all, Allan McCollum, began to take note of Mullican’s ideas and write about them. “For Mullican,” wrote McCollum in 1980 Real Life Magazine article, “the world of art describes a ‘fictional’ reality. However, since he recognizes the anatomy of the ‘real’ world to be made up of signs and symbols, the world of art and the world of reality obtain a queasy interchangeability.”

Mullican explored this relationship in performance pieces like “The List” (1973), in which he created a kind of stick figure in words. In short, monotonous segments, Mullican read fragments of a narrative of a fictive woman’s life from a list pinned on the rear wall of the performance space. He sat with his back to the audience to emphasize the illusion of objective distance. But the identity of the subject was not static; the narrative was broad enough that “she” could be anyone, including Mullican.

A couple of years later, Mullican ventured into a medical anatomy lab, where his various interactions wit the cadaver of an old man were recorded by a photographer. One of the resulting photographs, a portrait of the old man’s head, often figures alongside the portrait of a doll in what Mullican calls his “bulletin boards”—montages of photographs that the artist includes in most of his exhibitions. Is the doll, a living fictional person, more alive than the cadaver, a real dead one? In the mid-’70s Mullican began to use hypnosis to further test the boundaries between the real and the fictive, between the objective world and the subjective experience—to explore an entire house, for instance, of which he had previously visited only a single room. These journeys were taken, however, at the cost of some shock to the psychological and physiological systems—“I’m a fairly shy person,” notes Mullican. “When you’re under hypnosis, the crowd keeps pushing you to go down further”—and he quietly dropped the activity in the late ’70s.

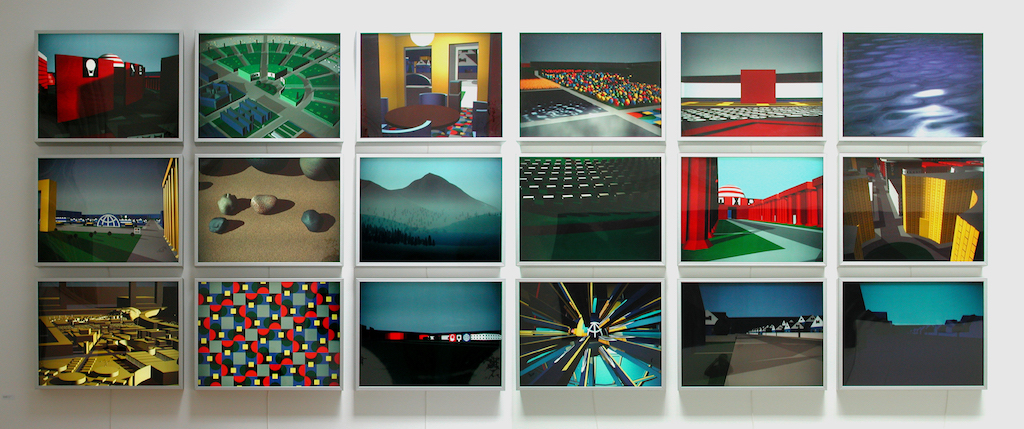

Matt Mullican, Untitled (Computer Project), 1989.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MAI 36 GALERIE, ZURICH

Besides, other ideas that had long been in gestation were just beginning to reach maturity. Since student days a keeper of “charts”—rough sketches that attempted to describe the nature of different levels of reality in notational form—Mullican had been evolving the “model of cosmology” that was to become a cornerstone in his work. A drawing dating from 1974, Cosmology Proper, sketches out a cycle of life from birth to death, along with a handful of symbols that, in time, would form the basis for a full-scale, encyclopedic system.

Mullican instists on distinguishing his model from an actual cosmology, a metaphysical model. “It’s a chart,” he explains, “in a formal sense. My work may have to do with the loss of spiritual values, but I’m not involved with God in any intimate way, so I remain formal in my approach to the subject. I call it a model to suggest distance and manipulation.”

The concept has the internal logic of a computer model—dimensional and hierarchical, categorizing multiple orders of experience into a quasi-objective representation of the way in which the subjective mind constructs them into a cohesive whole. Flat areas of background color in the models assist in signifying the relationships among these various levels fo experience: red indicates subjectivity; black and white, language and systems of signs; yellow, “the world framed”—a code for all the arts; blue, “the world unframed”—the world of everyday objects and experiences; and green, the elements of the periodic table—the world that precedes or exists beyond the perception.

Mullican’s ever-growing vocabulary of stylized signs also functions as a codifier in this overall system, enabling him to envision nothing less than a symbolic representation of the construction of all human knowledge. Inspired by the international signage system that they resemble, these pictographs range from the banal to the exotic. While some—the rest room, the knife, the fork—are borrowed directly from that international language, others are recycled from old texts, encyclopedias, and popular mythology, or are derived from the particular site in which he works.

A project two years ago in Munster, West Germany, for example, found Mullican paving the courtyard of the city’s Chemistry Institute with 35 five-foot-square slabs of granite that had been etched with images combining his own lexicon and that of his putative audience of students. “I included a hamburger and soda,” he says, “alongside a picture of a scientific instrument, alongside a cosmological model, alongside a city plan.”

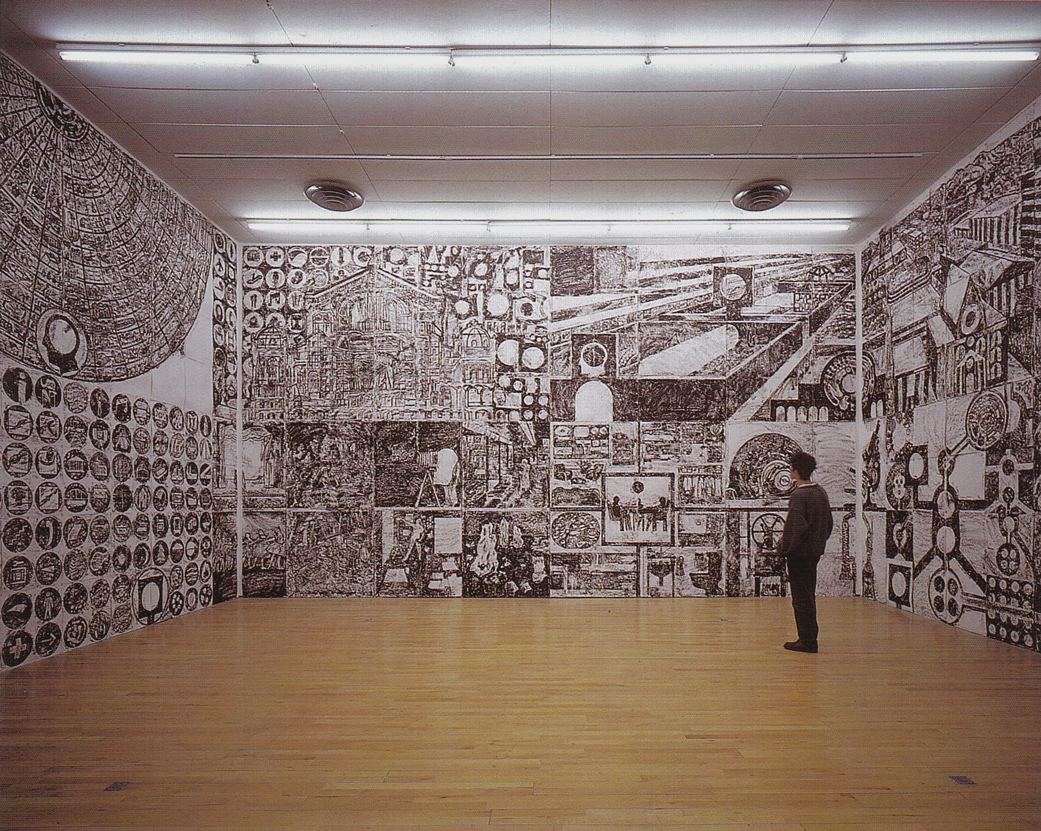

Matt Mullican, Dallas Project (Third Version), 1987. Installation view, Le Magasin, Grenoble, 1990.

GEORG RESTEIGER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MAI 36 GALERIE, ZURICH

The details of his systematic iconography of signs were years in the development, but Mullican had established a strong theoretical basis for his work by the late ’70s. He had also, on the strength of his performance work, gained recognition in the New York art world. Along with contemporaries Salle and Bleckner, Mullican was picked up by the dealer Mary Boone, who in 1980 offered him an exhibition. While his association with Boone was to last five years, Mullican recalls that he was “odd man out in the gallery. I was just starting to work with posters and banners, and it was pretty clear Boone would have a tough time selling them. But she encouraged me to do whatever I wanted, which was terrific. And she gave the work an acutely public image.” In a surely self-conscious and ironic awareness of this image, Mullican paired his own name and some weighty philosophical concepts on the posters of signs in his first exhibition at the gallery: “MULLICAN—GOD,” “MULLICAN—DEATH,” “MULLICAN—WORLD.” “The names,” he says, “represented my emergence into the public arena. I was especially interested in artists like Julian Schnabel and the way a name could become so important.”

Yet the public arena, for Mullican, proved to be something other than the established world of art collectors and museums. The poster and banners—unprecious, easily reproduceable mass communications media—suggested access to a general public that had no particularly commitment to or interest in art. New York dealer Michael Klein, who has represented Mullican’s work since 1985, encouraged this direction by actively searching for venues in which the artist could work without traditional gallery strictures. “If information was coming from the public,” says Klein, “it should go back to the public.”

For Mullican, the public forum proved important as another discovery of how context could inform the signs. “When I put an image on a flag,” he says, “I found it meant something very different than when I put it on a piece of paper,” citing the example of a 1986 installation at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. There, his black-on-yellow images on huge banners hung over the building’s facade were intended to refer in his own code to language systems and the “world framed.” In fact, as black and yellow are Flemish national colors, the banners provoked a public outcry; they were construed as a political statement concerning then-current infighting among Belgian ethnic groups. “Their system” he notes laconically, “was much stronger in that context than mine.”

Mullican’s public art explores how a culture imparts meaning to the things with which it surrounds itself. His work “becomes architecture in an odd way,” he explains. “People don’t question its presence physically. When you etch in stone, people aren’t worried about the value of the object. They’re not worried about it being avant-garde or alien. They’re just looking at the picture and they might want to understand what’s going on.” He is fond of a story about an exhibition in Philadelphia that included one of his earliest rubbings, the four-panel Untitled (Big Chart) (1984), which maps out a sketch of his cosmology. A young man was overheard explaining it as the fall of Western man. “He was trying to decode it, and was in a sense philosophizing about the nature of pictures,” Mullican says. “He might have gotten the symbols all wrong, but he was talking about the relationship of pictures to the world.”

Mullican’s discovery of granite as a durable and unusual etching surface contributed to his growing recognition and access to choice public projects in the early ’80s. Moreover, the images in stone suggested ancient stone rubbings to the artist, who began to use Masonite-and-paper templates to make his own rubbings of signs. Mullican takes plaeasure in the idea that the medium has a history of 2,000 years as a form of printmaking, and also finds in rubbing a paradigm of the distance he has always maintained between subjective vision and objective reality: “The rubbing becomes an echo of the relief, the record of the creation of an artificial history.” Mullican records his signs on canvas in black oilstick against the backgrounds of cool, flat areas of color. Early works of this kind, such as Untitled (Big Chart), led to grand pieces like a 1986–87 commissioned work for the Dallas Museum of Art that comprised 52 adjacent panels; its scope comes close to fulfilling Mullican’s dream of an encyclopedic artwork that documents the history of the world, as he says, “from the big bang to the future of mankind.”

Matt Mullican, Untitled, 2017.

COURTESY MAI 36 GALERIE, ZURICH

As a slow, labor-intensive equivalent of the visual process, the rubbings also reflect Mullican’s interest, from student days, in the way light constructs the images we “see.” The same is true of the computer-generated images in the project with which he is now involved. At its core is his current preoccupation with the “City,” a Borges-like model of human knowledge and experience that made its first notational appearance in the cosmology charts as early as 1979. “People were interested in the image from the start,” the artist points out. “They wanted to know what the City would look like, so it seemed appropriate that it should be described.” A substantial elaboration of the City appeared in a 1987 show at the Kuhlenschmidt/Simon gallery in Los Angeles, and was soon expanded to occupy a 20-panel section at the center of the Dallas project. And Mullican continues to explore its meaning and parameters in a variety of mediums, from a planar rendition in white porcelain to a three-dimensional model in Styrofoam at his Michael Klein gallery show last fall to a series of upcoming large-scale public commissions in L.A., New York, and Givors, France.

But it is a NYNEX-sponsored supercomputer project that affords him the power to conceptualize images and integrate them on an enormous scale—to create, in effect, his own enormous city—at John Whitney, Jr.’s Optomystic studio in Hollywood. Whitney’s brother, Mark, first spotted Mullican’s work at Kuhlenschmidt/Simon in 1987. “We were actively looking for an artist to work with,” explains John Whitney, “because we realized this was a way to expand our thinking about the way we had been using the computer.” The “Thinking Machine” (an innovative Connection Machine-2 computer designed by leading researchers in artificial intelligence at M.I.T.) is the most advanced imaging technology in existence. “We can take Matt’s work and describe the topology in three-dimensional mathematical form,” says Whitney. “The plan is to work together long enough to build from the smallest element to the largest. We can give this thing a scale that would be inconceivable without a computer.” The result, he says, “will be a massless, weightless, a city of ideas and icons, archetypes and relationships—a whole metamorphosis of morphology.”

It’s not only a matter of scale, then, but an expanded power to actually conceptualize the model. If the Dallas project, in its sheer length, allowed Mullican to extend his linear exploration of the City, the computer invites mind-boggling three-dimensional projections. “When you’re given any part of the City,” explains Mullican, “it’s going to change the way other parts look. When you look out from the blue area, for example—the level of the street and everyday experiences—all the other areas tend to look blue. So there is not one city, but five, because each area defines the others differently.”

Mullican stresses, however, that the project is still too young to predict what its final results might be. Even the scale remains undetermined—though the current projection is roughly two miles by four miles. The show at the Modern this summer will feature prints from screen images of parts of the City, exhibited in light boxes, along with a video monitor, related line drawings, and a poster blow-up of a City panorama.

At last report, the artist was back in New York, at work on a 12½-by-25-foot drawing of the City on his studio floor (in a scale of one inch to 65 feet). “It’s interesting,” he says, “because you have to be so clear. I’m laying out all the roads, all the buildings, and I want to get as much done as I can in the fastest way. Once I get the image into the memory, I’ll be able to feed off the computer more.” In the meantime, he says, he finds the hacker’s terminology compatible with his own. “I think of a cosmology as a machine, and the computer people talk about the ‘cosmology’ of the computer’s memory, and the ‘engine’ that generates its activity. I like that idea—an engine generating meaning.”

And the pressures and demands of the international art world? Will they allow him the time and leisure to explore the new medium? “I’m trying to space things out more,” says Mullican. “I have to challenge myself. You get known by a body of work, and people expect it of you. Then you feel a bit trapped, you get sucked in. . . . I’m terrified of that.” Yet he sees no end to the work he has to do. “People might know that I’m involved with a certain image, but they don’t necessarily understand all the applications of the image,” he says, adding, after a moment’s hesitation, “and that is after all my job, isn’t it? Finding out.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 1989 issue of ARTnews on page 142 under the title “Sign Language.”

[ad_2]

Source link