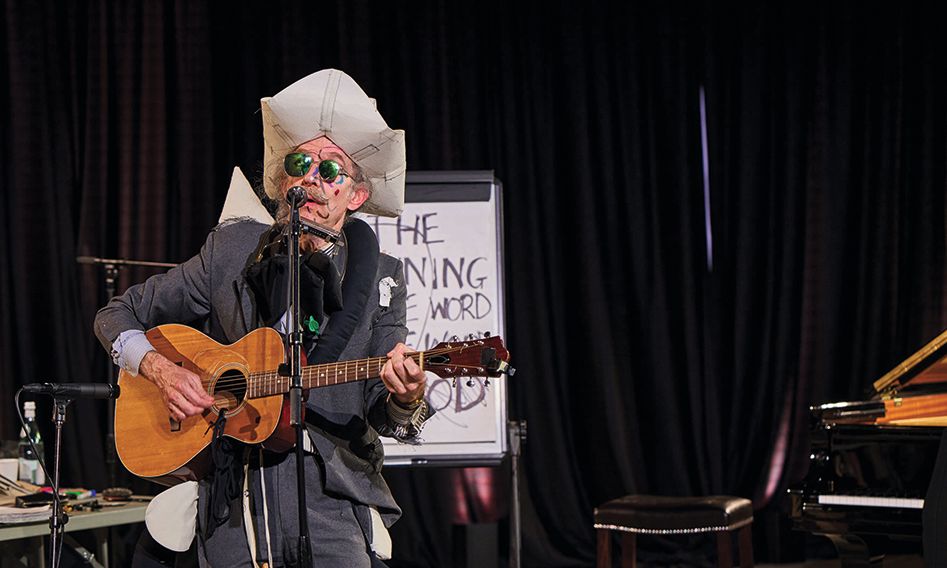

Martin Creed performing at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, 2022

Photo: Mario de Lopez; © Martin Creed, All Rights Reserved, DACS

Less is more for Martin Creed, the artist who famously won the Turner Prize in 2001 with Work No. 227: the lights going on and off. This audaciously minimal work was precisely that, an empty white room in which the lights went on for five seconds and off for five seconds, ad infinitum, or until someone deactivated the timer. But for Creed it was quite the opposite. “For me it’s a maximal work, because the whole space is activated by it—with your average object in a room, that doesn’t happen”, he told me at the time.

Over the years, Martin Creed has wowed the international art world by using often the most insubstantial of means to the most striking effect. Among these “big nothings”, as he has called them, are the various versions of his Half the air in a given space, which contain half the cubic volume of any gallery in hundreds or sometimes thousands of party balloons, which engulf visitors in a mass of bouncing, popping, squeaking packaged air. This overwhelming piece is currently transforming the ground floor of Museum für Konkrete Kunst in Ingolstadt, where Creed has a solo show beguilingly titled I Don’t Know What Art Is (until 3 March). Another conspicuous work was his resounding launch of the London Olympics in 2012 with Work No. 1197: All the Bells. This set the entire nation reverberating to a simultaneous three-minute cacophony of hand bells, bicycle bells, church chimes, ship cannons and even Big Ben, which, in a rare departure from its schedule, chimed 40 times.

Installation view of I Don’t Know What Art Is, at Museum für Konkrete Kunst in Ingolstadt, Germany

Courtesy of Museum für Konkrete Kunst

But conversely, Creed’s work can also sit so lightly on the world that it seems to vanish altogether, whether in stacks of chairs, piles of iron beams or Work No. 88: A sheet of A4 paper crumpled into a ball, which, when it was sent to art worlders back in 1995, often got binned by mistake. (Including, shamefully, by your correspondent.) Fearing the dilemma of choice, Creed can also plump for including everything: line drawings using all the colours in a pack of marker pens; wall paintings with criss-crossed lines going equally in both directions; or a series of “singing lifts” installed in galleries from the South Bank in London to the Van Abbe in Eindhoven. Here, meticulously harmonised voices sing all the notes from the bottom to the top of a scale, rising and falling as the lift goes up and down.

As he states in a neon sign that has been emblazoned on gallery walls and public buildings worldwide, “the whole world + the work = the whole world.” Such all-encompassing rigour chimes with much conceptual art, but Creed shies away from such labels. “I can’t separate ideas from feelings, I can’t separate from what is inside me, it’s all a big soup.”

Martin Creed's Work No. 232: the whole world the work = the whole world (2000) installed at Tate Modern

© Tate

Music has a key role in Creed’s everything-and-nothing work. As well as his many pieces featuring sound and/or instruments, he has also developed a parallel career as a musician and in 1994 he formed the band now known as Martin Creed and His Band. Music lies at the core of everything he makes. “You can’t separate music and life,” he declares. “You can’t look at something without listening to something and you can’t listen to something without looking at something—you can’t separate the senses.”

Creed’s performances now fill ever larger galleries, festivals and concert halls worldwide. It was therefore a rare treat to blast away the January blues last month with a full-throttle gig that packed out a modest room above the Betsey Trotwood pub in Farringdon, east London where a small crowd experienced the artist at his bold, yet self-effacing, best. Clad in a bizarre array of his wearable artworks, Creed and band members Keiko Owada, Karen Hutt and Sita Pieraccini belted out such pared-down songs as 1-200 using classic rock riffs with an escalating energy which has been aptly described as Steve Reich meets The Ramones.

There was more numeric wordplay in the minimally eloquent love song that declares: “I’m the one for you/I’m your two/You’re the one for me/You’re my three.” And we all related to the pathos of such poignantly existential numbers as What the Fuck am I Doing? and Mind Trap, where Creed sings: “I got myself into a mind trap/And now I’m looking for a mind trap map/I can get out of this mind crap/I’m looking for a mind crap gap.” In all its infinite forms and wryly illogical logic, the mind-gym art of Martin Creed offers a powerful tonic for both head and heart, and seems an appropriate prism through which to view what promises to be a febrile, unstable and contradictory year ahead.

• Martin Creed & His Band will perform live at The Betsey Trotwood, London on 5, 6 and 7 April, 2024.