[ad_1]

Why protest the detention of immigrants across the United States on Independence Day? When asked that recently, artist Dread Scott responded with a Frederick Douglass quote: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

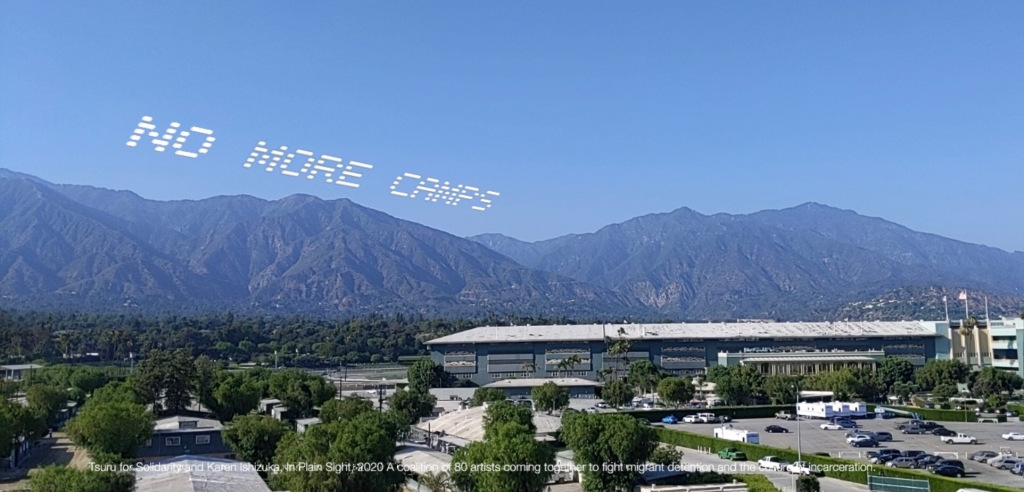

Scott is one among the 80 artists participating in “In Plain Sight,” a sprawling performance event launching today. Over the July 4th weekend, two fleets of skytyping planes will write artist-generated messages above 80 ICE detention facilities, immigration court houses, processing centers, and former internment camps. Each message will end with #XMAP, which, when plugged into social media, will direct to an online interactive map that offers a view of the closest ICE facilities to the user.

“In our imagination, immigration detention is something that exists along the Mexico-U.S. border, when in fact detention centers exist in every state,” said artist rafa esparza, who founded “In Plain Sight” with the Canadian performance artist and activist Cassils.

Visitors to the event’s website are encouraged to donate to local funds like the Black Immigrant Bail Fund and join the #FreeThemAll campaign, which advocates for the release of detainees from crowded facilities, where social distancing is often impossible right now. With “In Plain Sight,” esparza and Cassils are hoping to educate viewers—and to encourage the abolition of facilities such as these.

“I think the public is somewhat aware of what’s happening in detention centers—they’ve seen the images of kids in cages—but they don’t know the full scale,” said Cassils. “This project is about having faith that if people knew there was a facility across from the IKEA in Brooklyn where detainees were being tortured at the expense of their own tax dollars, then they would do something about it.”

esparza and Cassils, who are both known for work that considers the body in political ways, are intimately acquainted with the U.S. immigration system. esparza is the child of working-class Mexican immigrants; Cassils recently finalized immigration from Canada, a journey they recounted as expensive and rife with transphobia. But the artists’ latest project reaches far beyond their own biographies in ambition.

“So often artists, and especially performance artists, are asked to operate with very little support and that dictates the breadth of expression that we have,” said Cassils. “We wanted this to be a large-scale event because we wanted a massive impact.”

The artists reached out to the only skywriting company in the country (which owns the patent on skywriting) and learned that the largest campaign executed over U.S. soil involved about 80 sites and three fleets of planes. That established the project’s framework, and from there they went about the task of bringing on collaborators, many of whom have experiences with immigration and the detainment of oppressed minority groups. The artists they tapped vary in age, gender identity, and nationality; some are formerly incarcerated, or are descended from the descendants of Holocaust survivors. Black, Japanese-American, First Nations and Indigenous perspectives are present, speaking to the historical intersections of xenophobia, migration, and incarceration. The roster includes Hank Willis Thomas, Zackary Drucker, Emory Douglas, and Titus Kaphar.

Coordinated demonstrations by local and national immigration organizations, such as the ACLU of Southern California and the Detention Watch Network, will take place at detention sites simultaneously. Outside Yuba County Jail in Marysville, California, activists will fly kites—an allusion to how, in jail, the phrase can refer to an anonymous grievance made about prison conditions. Make the Road New Jersey, a partner organization with “In Plain Sight,” will be staging demonstrations outside a detention center in Elizabeth, New Jersey. The facility is about a 10-minute drive from Newark International Airport, in an area that is industrial and quiet, save for the planes overhead; no public sidewalks lead to or from the center. With the help of Make the Road New Jersey, its detainees filed a class lawsuit against the center in response to the public health crisis unfolding inside. Similar cases have been files on behalf of detainees at the Eloy Detention Center in Arizona and the nearby facility La Palma. To date, over 2,700 ICE detainees nationwide have tested positive for Covid-19.

“Now, detention can be a death sentence. It’s a tinderbox in there,” said Sara Cullinane, a leading member of the organization. No one involved in the inception of esparza and Cassils’s project could have predicted the coronavirus pandemic, but its emergence, and its convergence with the Black Lives Matter protests, inevitably reframed concerns.

Scott, who joined the project in its early stages, edited his original message in accordance. “Once Covid started in America, Black people and immigrants—many who were forced to butcher hogs in unsafe conditions so we could have hot dogs on the Fourth of July—began disproportionately dying,” Scott said. “I was really angered that there was this willful blindness to such actual suffering.”

Scott was assigned one of New York City’s oldest former detention centers. Written overhead, and visible for miles, will be the words “Carlos Ernesto Escobar Mejia,” the name of the first recorded death in ICE custody resulting from causes related to Covid-19. The 57-year-old Salvadorian immigrant had been held at the for-profit facility Otay Mesa in San Diego. After days of confinement among other sick detainees, Escobar Mejia died on May 6.

“I think that the full majesty of this project is only realized when people stick the components together,” said Scott. “They will make you think about what and who is erased from American history.”

Written nearby Escobar Mejia’s name will be a quote from his sister, spoken upon learning of his death: “My pain is so big.”

[ad_2]

Source link