[ad_1]

Luchita Hurtado, Encounter, 1971, oil on canvas.

BRIAN FORREST/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND PARK VIEW / PAUL SOTO, LOS ANGELES AND BRUSSELS

The fourth iteration of the Hammer Museum’s Made in L.A. biennial has neither subtitle nor unifying theme, as perhaps befits a regional biennial in a sprawling megalopolis like Los Angeles, one organized moreover during a period rocked by various protest movements, renewed debates about identity politics, and intensified partisanship across the political spectrum. Instead of imposing a didactic framework (or, heaven forbid, trying to determine an “L.A. aesthetic”), curators Anne Ellegood and Erin Cristovale have thoughtfully presented a wide-ranging selection of works by a group of artists varied in age, gender, and racial and ethnic backgrounds. Notably, a majority of the artists are women, queer, and/or people of color. Collectively, the artworks offer a multiplicity of perspectives while also sharing broader, often overlapping interests and issues, including the representation of bodies and bodily experience; environmental destruction and ecological concerns; the unearthing of repressed histories on local and global levels; and engagement with specific sites and locales in and around the city. The exhibition’s most significant takeaway was that issues regarding social identity cannot easily be isolated from considerations of lived experience, climate change, histories and mythologies, and spatial politics.

Bodies were a prevalent theme throughout the exhibition, particularly fragmented ones that pressed up against the limits of representation in ways that seemed both liberating and destabilizing. A sense of vertigo permeated Luchita Hurtado’s paintings of downward-facing partial views of her own nude body, whereas Naotaka Hiro’s visual metaphors of fissures and voids in drawings and sculpture portrayed the body as structured along an axis of unknowability. Illegibility and illusion characterized the flattened, multicolored figures and tromp l’oeil wallpaper installation by Christina Quarles, while Suné Woods’s immersive video installation, Aragonite Stars, revolved around bodies of water and of black people, tenderly embracing or freely moving in the medium, loosened from the constraints of gravity—and repressive social conditions—on land. Diedrick Brackens’s tapestries depicted allegorical scenes of silhouetted black male figures and animals (one based on a real-life event in which three black men were arrested and handcuffed for a misdemeanor and drowned after being transported on a boat that capsized) to address the social constructions of masculinity and African American identity in relation to a history marked by wrongful deaths, negligence, and injustice.

Candice Lin, La Charada China (detail), 2018, mixed media, installation view.

BRIAN FORREST/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GHEBALY GALLERY, LOS ANGELES

In a moving display of persistence, endurance, and resilience, E. J. Hill stood stoically on a podium every day during the museum’s opening hours for his work, Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria, for the entire three-month run of the exhibition. Surrounding him were a makeshift running track around the vault gallery’s perimeter and photographs of him (taken by fellow artist Texas Isaiah) running a “victory lap” around the schools he attended but felt excluded from in Los Angeles as a child and, later, as a queer, black adolescent and young adult. Although Hill remained silent as he stood on the podium, a neon sign that backlit his body asked viewers a powerful rhetorical question: “Where on earth, in which soils and under what conditions will we bloom brilliantly and violently?”

A number of artists responded to ecological concerns and environmental devastation, especially those wrought by the forces of capitalism, in their respective works. Carolina Caycedo suspended a series of large-scale fishing nets in a kaleidoscope of colors in the Hammer’s courtyard. Part of her ongoing Be Damned project, the nets were acquired during the artist’s time spent in communities affected by the building of dams and privatization of waterways in Latin America, and hung with objects collected during her field work to represent resistance fighters and inspiring people she met along the way. Littered riverbanks and smog-filled cityscapes appeared in Neha Choksi’s multichannel video Everything sunbright, a poignant rumination on mortality and the human life cycle, as well as the sun’s eventual expiration. Charles Long filled a room with papier-mâché tree stumps and sliced logs that resembled cross-sections of oversize penises, in a fantastical and biting vision of a castrated forest—and patriarchy.

Revealing marginalized or overlooked histories was another approach taken by several artists. Mercedes Dorame’s photographs and sculptural installation addressed her ancestral connection to Tongva people, who were among the first inhabitants of the Los Angeles basin and the last of whom were said to have “died” from disease and dispossession of land (or so misleadingly claimed a book the artist found in a library). Candice Lin took as her subject the little acknowledged importation of hundreds of thousands of Chinese laborers to the Caribbean to work alongside African slaves in the 19th century, and the Charada China, a gambling game and syncretic ritual used to redistribute wealth within the diasporic community. Rosha Yaghmai projected onto a resin-and-steel screen adorned with personal effects a series of color slides that she had uncovered in her family’s photo archive, images that her father had taken soon after immigrating from Tehran to California to study his new surroundings and culture.

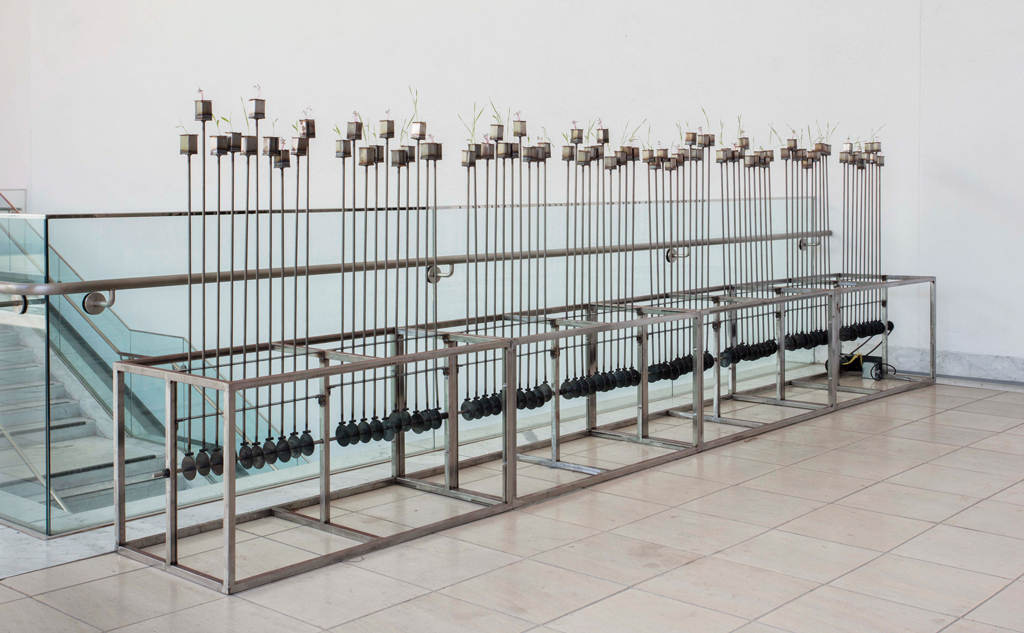

Beatriz Cortez, Piercing Garden, 2018, steel, motor, and indigenous plants from the Americas, installation view.

BRIAN FORREST/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND COMMONWEALTH AND COUNCIL, LOS ANGELES

Other artists sought to engage specific sites or locales in Los Angeles and its environs. Lauren Halsey presented a prototype for her Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project, a mausoleum-like monument made of plywood and gypsum tiles to be realized along Crenshaw Boulevard on the former site of an African bazaar that the artist had frequented growing up. Etched onto its surfaces were inscriptions, local storefront signs and landmarks, portraits of family and friends, and lists of names belonging to those who had recently died at the hands of policemen. One version of Beatriz Cortez’s Tzolk’in, a large steel kinetic sculpture whose movements are based on the Mayan agricultural calendar, appeared on the terrace of the Hammer Museum, which is located in Westside Los Angeles. Another, larger version of the piece was installed on the city’s Eastside, at the Bowtie Project space in Glassell Park, a postindustrial strip of land along the Los Angeles River. A surveillance camera at the latter location made possible its viewing in real time on a screen at the Hammer, this unidirectionality being intentional, since, as the artist has pointed out, both sites don’t “offer the same circumstances or opportunities.” Gelare Khoshgozaran’s video Medina Wasl: Connecting Town combined interviews with U.S. veterans who were deployed to the Middle East with footage of military training camps, towns, and other areas in Southern California, where structures have been built to resemble those in the Middle East.

The exhibition’s most memorable artworks were ones that employed an aesthetic of contingency as well as an ethical sense of incommensurability and the impossibility of representation. The first performance of taisha paggett’s ongoing work counts orchestrate, a meadow (or weekly practice with breath) was a slow burn, unfolding over the course of two and a half hours in the Hammer’s courtyard. To a soundtrack of people breathing and a preacher speaking about racial justice, the artist weaved her way through the audience that had gathered to see her, first moving freely in the central empty space formed by a crowd, then insinuating her body through the crowd, crawling on and under benches, and, finally, after the crowd had thinned out, allowing her body to fall gently onto audience members, whom she subtly guided to pass her body onto other members, creating a drawn-out and charged moment of public intimacy. James Benning’s three-channel video projection showed the aftermath of a vast forest fire in the Sierra Nevada Mountains that forced Benning to evacuate his home temporarily; an imageless slide with textual captions transcribing radio transmission from a U.S. B-52 fighter pilot flying around Hanoi on Christmas Day in 1972; and light from a slowly setting sun falling onto a framed drawing of a Native American man. Listening to the scratchy audio of the pilot helping coordinate the largest bombing campaign of the Vietnam War while trying to evade the approaching Vietnamese fighter planes, I felt a sense of horror in the pit of my stomach. The juxtaposition of images and audio brought on thoughts of U.S. imperialism at home and abroad, the inability of language to convey the scope of large-scale destruction, and the wordless depths of trauma.

This year’s Made in L.A. was evidence of a flourishing of art by a diverse body of self-aware practitioners, which is heartening in an age of increasing intolerance and conservatism. It’s time now to ponder this city’s mounting affordable housing problems, growing economic disparities, and the role that art is playing in the gentrification of neighborhoods in the southern and eastern parts of the city. How will all of that play out? We’ll see in two years, with the next biennial.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 126.

[ad_2]

Source link