[ad_1]

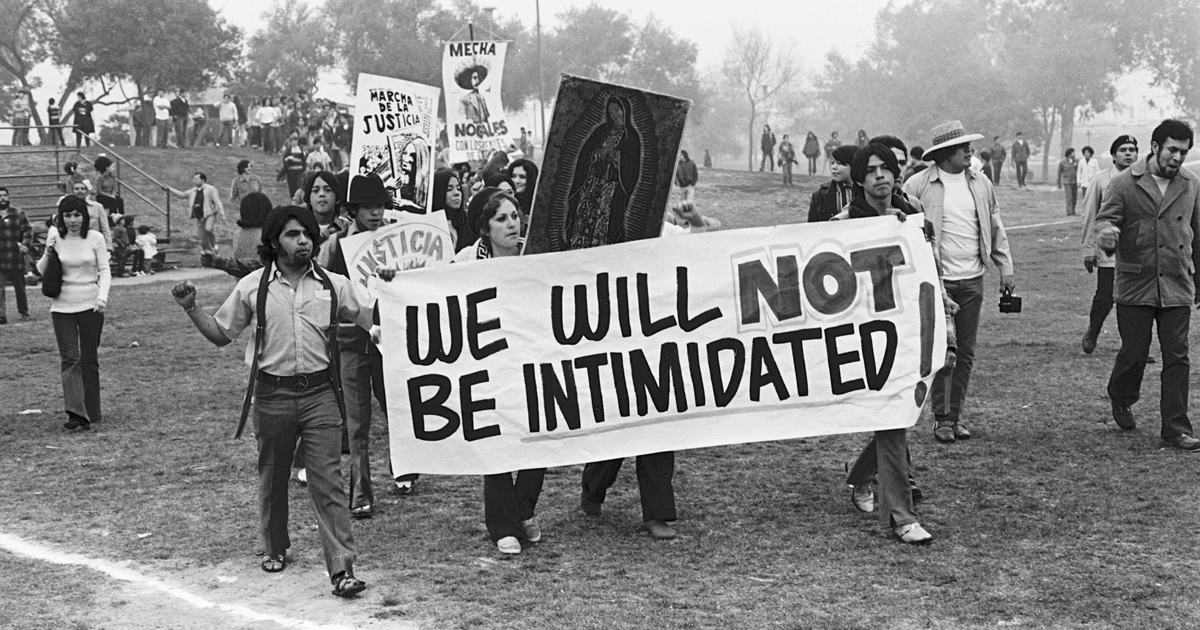

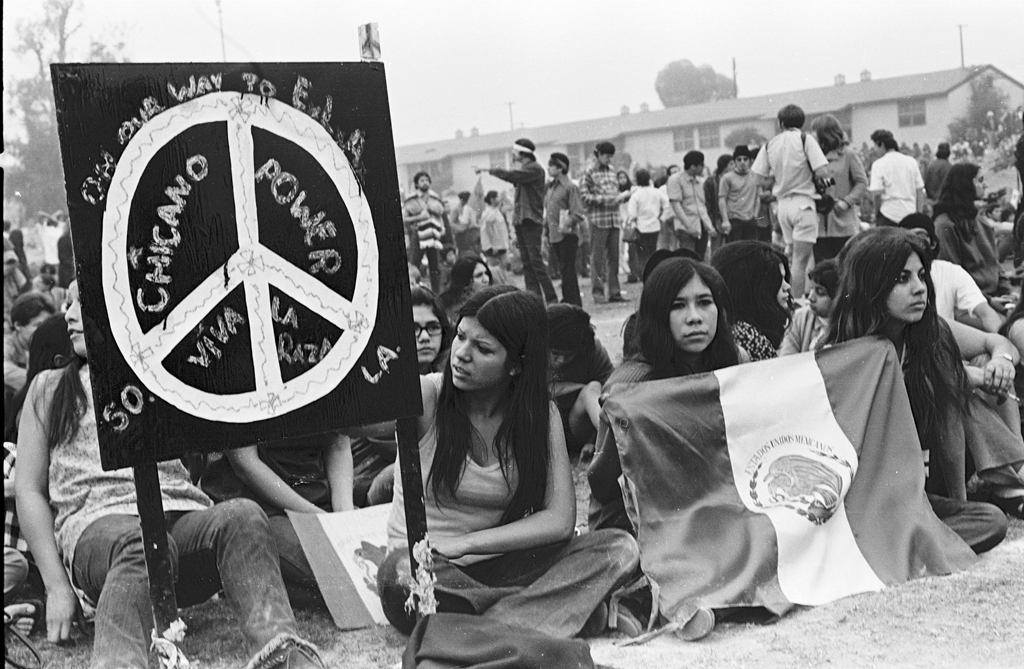

Luis C. Garza, Student and barrio youth lead protest march, La Marcha por La Justicia, Belvedere Park. January 31, 1971, 1971.

©LUIS C. GARZA/COURTESY THE PHOTOGRAPHER AND THE UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER

Over the past two years, there has been a marked uptick in high-profile political action by students in the United States, with young people staging protests in support of causes like stricter gun laws and maintaining the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals programming. On April 20, efforts to combat gun violence culminated in a National School Walkout across the nation, an event that harkened back to similar events in the 1960s, such as the Chicano Blowouts, in which hundreds of students from five high schools on the Eastside of Los Angeles walked out from their classrooms to fight for a better educational system. Among their criticisms was that schools with majority Chicanx populations were often geared toward vocational training instead of college-prep, which was common in predominantly white schools.

This March marked the 50th anniversary of those walkouts, and as part of the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, the Autry Museum in Los Angeles organized an exhibition looking at the photographic material of La Raza, a Chicanx publication that documented the Walkouts and other activism of the Chicano Movement. The exhibition provides a concise history of the tremendous output that La Raza’s photographers created, numbering some 26,000 images. They sought to serve as witnesses to this movement and its people, at a time when mainstream outlets ignored their calls for equity.

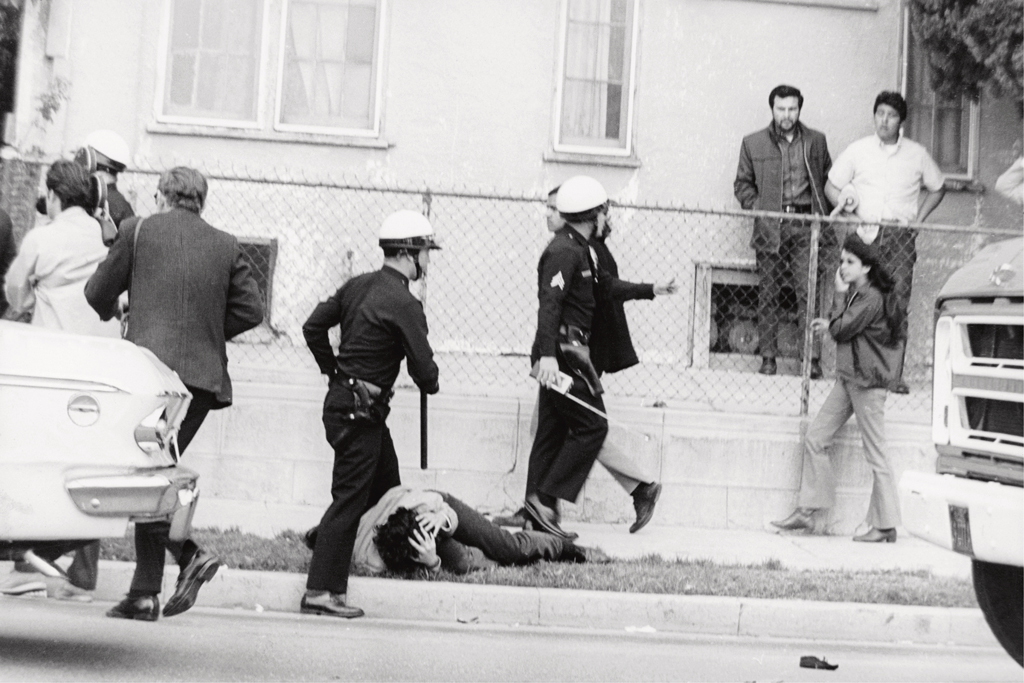

The photographs in the show range from shots of the Walkouts and other later peaceful demonstrations to images of police reacting violently to community members exercising their right. Among the most famous images are those capturing police officers launching tear gas into a bar, which would result in the killing of Chicano Los Angeles Times photojournalist Ruben Salazar. Also included in the archive are candid moments of young people interacting during these marches, views of the plainclothes officers surveilling the people, and people in domestic spaces, preparing for a protest or their bodies recovering from the violence inflicted.

Luis C. Garza, who was a La Raza photographer, co-curated the Autry show, which runs through next February. Another Chicano photographer George Rodriguez, who produced images in the same vein of those published in La Raza while working independently, also recently released a book of his images, Double Vision: The Photography of George Rodriguez (Hat & Beard), and a retrospective of his work will open later this month at the Lodge in Los Angeles. ARTnews spoke with Garza and Rodriguez about their work and the continuing legacy of the 1968 Chicano Blowouts.

ARTnews: How did you get involved with La Raza, Luis?

Luis C. Garza: I was introduced to La Raza in late 1967, ’68 by Ed Bonilla. He was a community activist here in Lincoln Heights. He introduced me to Chicanidad and that came about because I was searching for work. Now I had never heard the word Chicano [but he gave me a job]. And I said, “Fantastic! What’s the job?” and he said, “Organizing the people.” I said, “How do you do that?” He told me to bring my camera with me tomorrow morning, and that’s how I’m introduced to the Chicano Movement and La Raza, so I begin photographing with seriousness and intent and purpose. That gives me a whole new pathway.

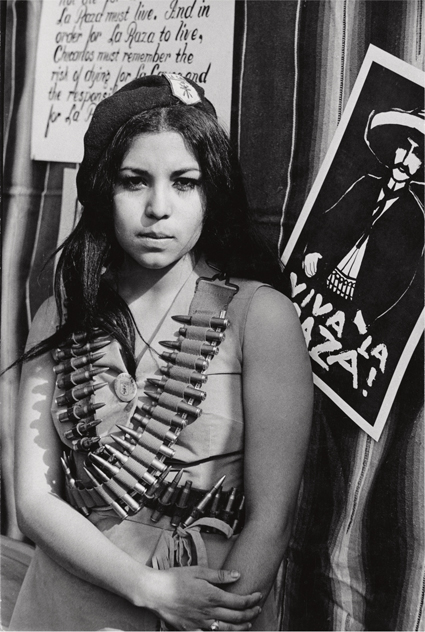

George Rodriguez, Lincoln Heights, 1969.

©GEORGE RODRIGUEZ/COURTESY HAT & BEARD PRESS

ARTnews: And George, how did you get involved in photographing the Chicano Movement in the 1960s and ’70s?

George Rodriguez: At the time, I was looking at Life magazine and seeing the incredible photographs of the Civil Rights Movement. When I saw that something was happening with Chicanos in East L.A., I thought: I want to cover this. I was constantly trying to cover as much as I could, when I could. It was so new, and it seemed like there were no formulas other than to look at what the Civil Rights Movement had done. And it was really serious, a lot of people could’ve gotten in a lot of trouble, and some people did, and some paid with their lives.

ARTnews: Looking through many of these images, you start to see an aesthetic take shape. Can you talk a bit about the approach you took to taking these photographs?

LCG: I think, George, you’ll find a lot in common with what you shot and what was shot on behalf of La Raza. The scope of the content is just enormous, from the mundane to the magnificent in terms of the images. You begin to see the photographic eye of some of the individual photographers take shape and evolve, in some cases. Working with my fellow colleagues at the time, it was a mentoring experience. Working in the darkroom also gives you that foundation because when you’re looking at the shots, you begin to see the planes, the light, your exposures.

One thing I cultivated for myself was the photographic eye: composition, framing, a conscious thought into what you were photographing, and the messaging of what you were trying to convey, be it political, artistic, aesthetic, or whatever the emotion was that was running through your veins. That begins to set a career path which is what La Raza did for me. I found myself in photography. Photography introduced me to the art of storytelling. My photographic work is principally, and I think George’s as well, in the street.

GR: You’re like me, you always have your camera.

LCG: Everywhere I went.

GR: People don’t know who I am unless I have my camera with me.

LCG: Yeah. It’s an extension of yourself. You live and breathe with it, you sleep with it, you eat with it. That’s the way that I approached photography from the beginning and even more so all those years that I worked with La Raza.

George Rodriguez, Boyle Heights, 1968. “Some kid got hit on the head by the cops during the Walkouts. I called these images ‘a field day for the heat.’ They were just kids.”

©GEORGE RODRIGUEZ/COURTESY HAT & BEARD PRESS

ARTnews: In the late ’60s and early ’70s, did you ever think that either of these works would be considered from an aesthetic point of view as works of art?

GR: Not me, I know that I love photography more than other things, but no I never thought I’d do a book. I feel very fortunate that there’s enough to tell a story.

LCG: I never viewed myself as an artist. Even to this day, in those moments when someone approaches me and refers to me as an artist, I look at them and I say, “If you say so. I’m not going to argue with you.”

ARTnews: Both of you sought to photograph not only the activism—the protests and marches—in your now iconic images, but the activists in more domestic settings, what George termed “the lives behind the politics.” Why did you think that was necessary to capture?

Luis C. Garza, Homeboys, Aliso Pico Housing Projects, East Los Angeles, 1972.

©LUIS C. GARZA/COURTESY THE PHOTOGRAPHER

LCG: For me, I start off photographing my family and my immediate surroundings. I have a history of capturing people and the human condition. I began paying attention to the photographic camera as a tool. Learning the technical aspects was one thing, but mastering it and seeing how it interprets what you see became so important to me. It was a period of personal confusion for me. The chaos, the conflict that was going on. When you look at the ’60s and ’70s, the constant events and demonstrations, all of these things that were going on, it was trying to make sense of it, and the camera helped me make sense of it.

GR: For me it seemed like the good photographers were taking pictures when other photographers were standing around waiting for something to happen. That’s why I wanted to document the Chicano Movement because you do it for the people who aren’t there. You have to show them what’s going on, especially the violence. Originally, I just shot a lot of political things and then I realized that I had to shoot the culture more than just demonstrations and marches. You try to show what we’re about. We’re a deep, beautiful, and artistic culture. We tried to bring that into our photographs. In a way we’re very different, but our goals and wants are exactly like everybody else.

LCG: A good portion of the shooting, especially when you’re at demonstrations, you capture the moment on the fly. You’re shooting as you’re running, but then you have these tranquil spots in between. But it’s not just demonstrations. There’s far more. We go beyond the borders of East L.A. The photographic materials go into Mexico, the Southwest, throughout California, New York City, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Budapest in Hungary, and the Soviet Union. It covers a much larger humanity: events and peoples and places and things.

ARTnews: The exhibition opened slightly before 50th anniversary of the Chicano Blowouts in March. How does that marker relate to what’s going on in this country today?

LCG: The Autry Museum exhibition is really a first chapter. The current politics of what’s going on in this country right now resonates. The comparisons to the past to the present is constant. Time bends in from 50 years ago to now. People have said [to me], you wouldn’t know it was 50 years ago because it seems so relevant to what’s going on today. With the anniversary of the East L.A. School Walkouts, people’s interest has resurged in terms of coming to the exhibition, looking at the work, and seeing and feeling the connection, seeing the reflection of themselves within the exhibition. It’s an incredible process that is going on right now, an emotional process for many visitors to the exhibition. I’ve had people come up to me and say to me, “I understand my parents a lot better now.” It resonates on a human level, on a universal level. George’s work reflects that humanity. My work reflects that, as so many of the other photographers also reflect that. It’s a testimony and it’s a legacy that is well-deserved to [the people in the photographs] that they would not have gotten otherwise.

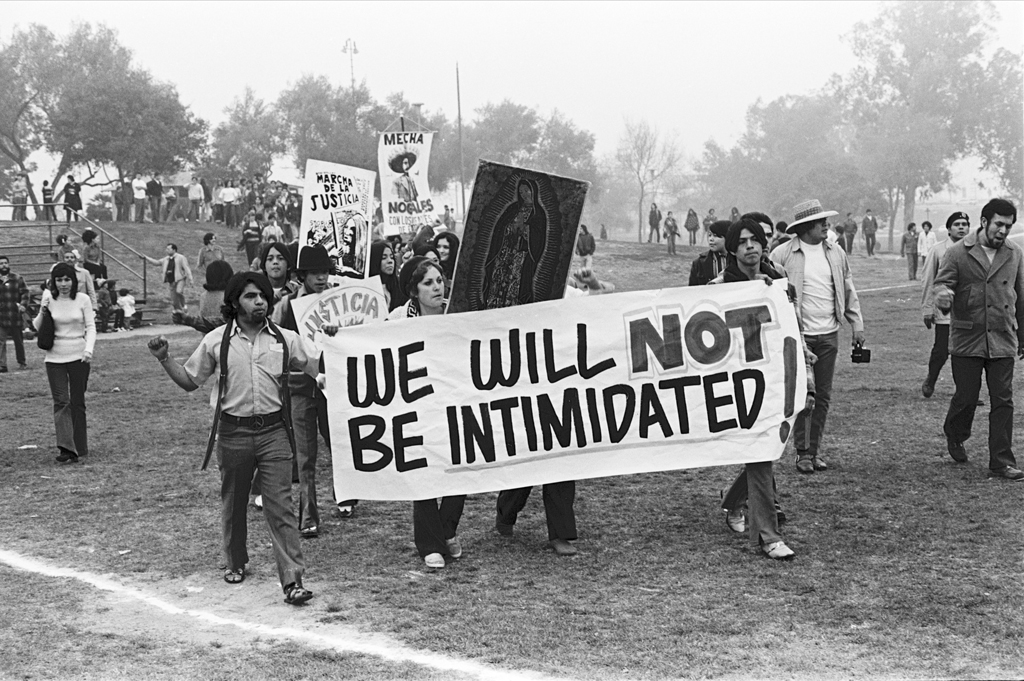

Luis C. Garza, Youth from the Florencia barrio of South Central Los Angeles arrive at Belvedere Park for La Marcha Por La Justicia. January 31, 1971, 1971.

©LUIS C. GARZA/COURTESY THE PHOTOGRAPHER AND THE UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER

GR: Of course, it’s topical. Things don’t change. They change, but not that much. Things are all the same. The issues in the Walkouts were about better education, so maybe the issue is different, but the young people are the ones at the forefront trying to make changes. During the walkouts, I really admired the people who really were trying to improve their lives. In a way, it’s a statement that they really suffered, especially the kids.

ARTnews: Why do you think that the images themselves still resonate today? What about them makes them timeless in a way?

LCG: Why do some photographs, and not all photographs, resonate? It’s a very personal thing; it’s very subjective. It resonates with some people on a combination of intellectual and emotional levels, and they are timeless because they do exactly that. There are times when I go into the exhibition and I’m just watching and listening to people. There’s always that comment, “It speaks to me.” And you know, “OK, it speaks to you. What is it saying to you? If that picture is worth a thousand words, what are those thousand words that is being spoken to you?” Break it down. I’m always curious, but I don’t want to interrupt the process. I just observe and take it in. That is the photographer that I am. As a photographer, you’re behind the scenes.

George Rodriguez, Cesar Chavez, Delano, 1969.

©GEORGE RODRIGUEZ/COURTESY HAT & BEARD PRESS

GR: For sure, you try to be the fly on the wall. A while back, I did an exhibition on Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers. One thing I never counted on was actual farm workers coming to see the photos and for them to know people in the photos. For them it’s not historical, it’s their lives. I recall a couple people actually crying because they remember how difficult those times were. I never realized that part of it.

LCG: That’s the other thing that grips you as a photographer. It is la gente del pueblo, the salt of the earth people. You realize how much a part of them you are. You are not apart from, you are a part of them, and that humbles me.

This exhibition is giving light to fellow photographers whose work deserves to be seen and gifted into the history of Chicano photographers. And I say Chicano photographers because that’s how I began my photographic career—as a photographer of Mexican background who comes into the Chicano Movement and adapts the self-branding identity of Chicano, which I still to this day wear with honor. That’s important because what we are doing is resurrecting a sensibility about us as a people in this continent. That’s the other significance of the exhibition which resonates. It’s, as Harry Gamboa says, filling the void, the void of recognition. This is a vast void of no recognition of who we are. And all of this work—George’s publication, the exhibition—is significant and important. The photographic body of work is just one representation of many different representations that we as a people have impacted society. The demographics speak for themselves and the demographics are frightening to that element of America that rejects us on every level. Why does it resonate? Because we took a stand, we took a position, we documented who we were as a people, and that continues to this day.

ARTnews: Is that the legacy of that era, taking a stand and documenting it?

LCG: It’s an ongoing legacy. The past and present continue into the future. There’s no break. There’s no stop in the Movement. Don’t separate 50 years ago from the present as if there’s a stop. There is no stop. This is just a continuation. What we have done is to pass the baton to those future generations. The current conversation is: How do we incorporate this material into the curriculum? How do we translate this material to any number of other imaginative ways? The fight is not over. This is just the beginning. And it is extremely important for this generation and for future generations to see what has been done, what is being done, and what needs to be done.

[ad_2]

Source link