[ad_1]

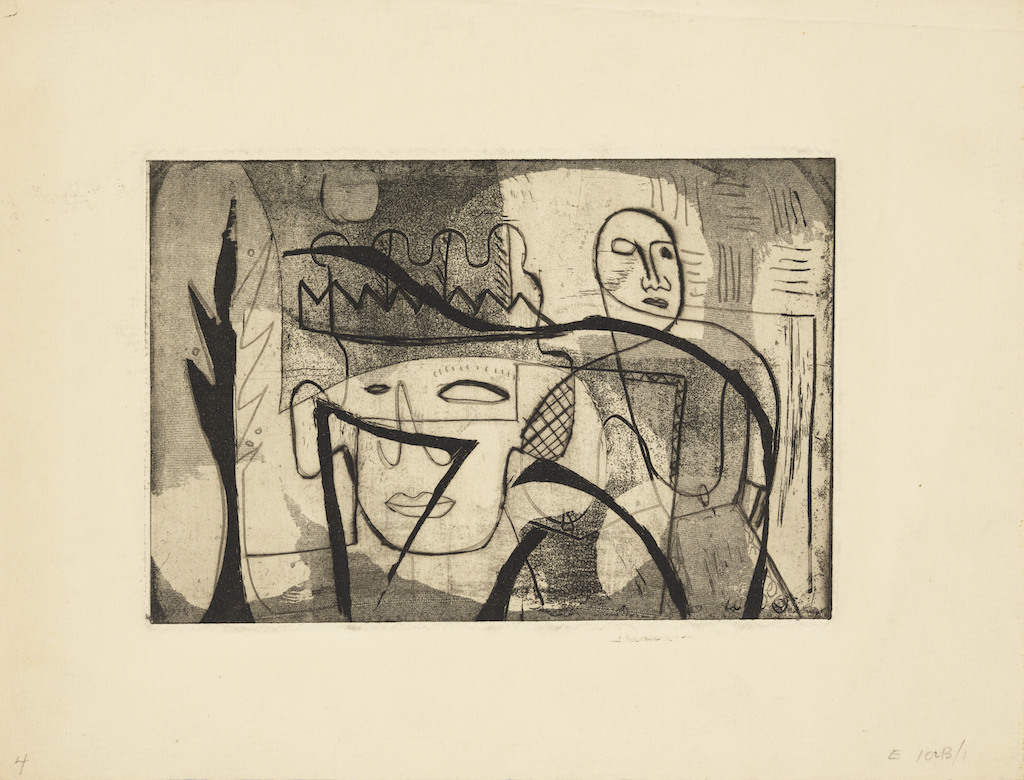

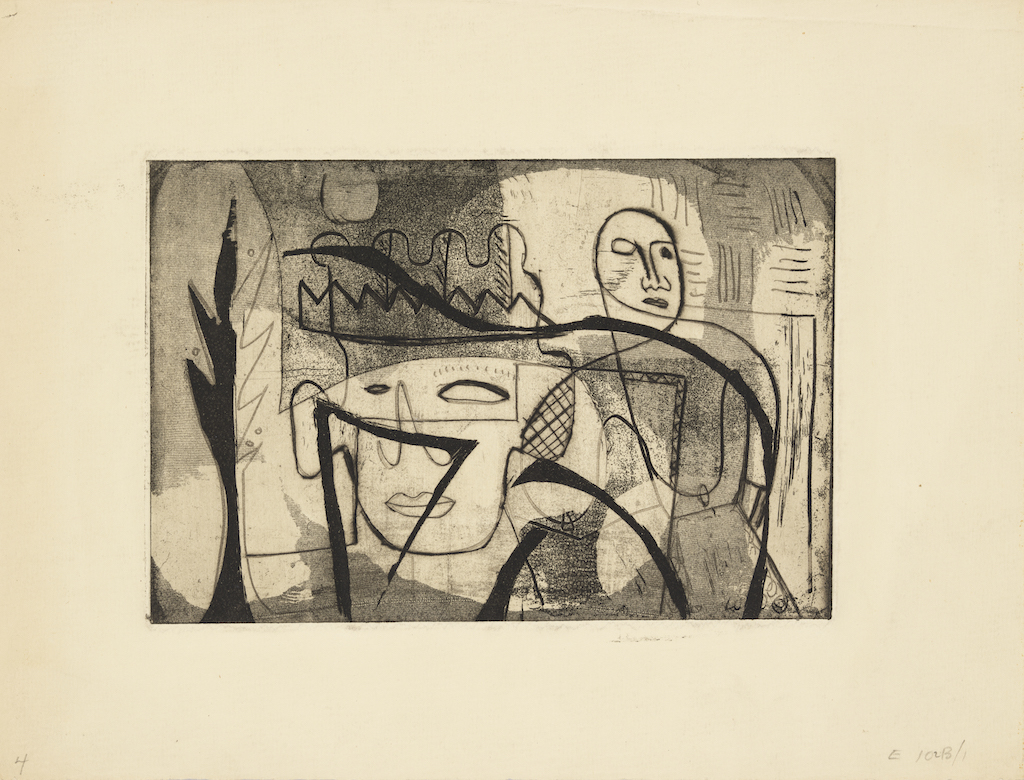

Louise Nevelson, The Magic Garden, 1953–55, etching and aquatint.

©2018 ESTATE OF LOUISE NEVELSON/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK, PURCHASE WITH FUNDS FROM THE PRINT COMMITTEE 96.193

Currently on view at the Whitney Museum in New York is an exhibition of prints and drawings by Louise Nevelson, who’s best known for her large, monochromatic sculptures, many of which resemble machinery parts arranged in cabinet-like compartments. In addition, conservation is currently being done on a chapel that Nevelson designed for the Citigroup Center in Manhattan that opened in 1977. With both projects in mind, republished below is an interview the artist did with ARTnews, originally printed in the October 1974 issue. Much of the interview is focused on the artist’s late-career output, with an emphasis on her studio habits. What does she do all day when not working? Mostly reading, because, she tells Barbaralee Diamonstein, “I don’t want hobbies, slobbies. I can’t even stand movies.” The interview follows below. —Alex Greenberger

“Louise Nevelson at 75: ‘I’ve never yet stopped digging daily for what life is about’ ”

By Barbaralee Diamonstein

October 1974

“Being Jewish and coming from Maine was no picnic,” said Louise Berliawsky Nevelson, who sold nothing from her first one-woman show in 1940 and burned the collection in an empty lot because there was no room for the works in her studio. Nevelson, who once said, “I still felt like a winner, I am a winner,” has won a crescendo of critical superlatives and public acclaim that will increase significantly this year as she celebrates her 75th birthday on September 23 or October 16.

Why two dates? “My parents emigrated from Russia when I was five. They were lucky to bring me at all, without a birth certificate. We moved to Rockland, Maine, and all I knew was that the date I was born depended on a certain Jewish holiday. A relative in Rockland gave me the birthday of October 16, corresponding to the holiday. Years later in New York, I got interested in astrology and went to a synagogue where they said September 23 was birthday. Being born in Russia and not knowing the right date wasn’t a good beginning for astrology.”

The legendary Nevelson is tall and striking. Her voice is vibrant; her heavily made-up eyes are intense under layers of false lashes and her skin is tight over high cheekbones. Nevelson, once described as the “roiling unstabilized force of arrogance and shyness, of selfishness and generosity, of disdain for the world and love for it, of anger and forgiveness,” is wrapped in Nevelsonesque dress—something of a cross between a princess and a peasant—Scaasi brocades, denim work clothes, ethnic jewelry and a floor-length sable. “I’m like Charlie Chaplin,” she said. “If I’m not dressed right, I can’t talk.”

“My whole life is very important to me,” she said. “I claimed my life long ago. I saw from the very beginning how one exploits another in the world, and saw the most important thing was to claim my life totally.

“John Cage told me recently, ‘I’m working like a beaver.’ He works constantly. He says there’s no room or desire for entertainment or vacation, and no matter how long he lives he can never do all he wants. I feel pretty much the same way. Miró, at 88, was recently asked if he ever thought about death—and he, of course, said no, he was too busy.

“My work is the mirror of my consciousness. In my own work, I think there is a beyondness, some call it mystery. It contains the awareness of love, or sorrow, all the human emotions. Almost everyday we live a world. The dawn comes, dusk falls. Some people call it a day. In my world, it is an eternity.

“I was born, I think, with a philosophy. I remember when I was six years old at play recess in school. One girl was taking advantage of another. So I went up to the girl who was being bullied to reassure her that she didn’t have to be conned. And she wasn’t even a friend of mine. At six years old you don’t battle for people unless you’re born with it. It’s like an egg; you can scramble it, soft-boil it, hard-boil it, even devil it. But it is an egg. The ingredient of an egg is an egg.

“Everything I do more or less comes from the center of my being. I won’t let someone superimpose on me. Who’s more important to one’s life than one’s self? Sometimes you have to turn around the things you are taught. For example, you have to be humble and you’ll inherit the earth. I don’t believe that. Unless that is your choice and you understand it. If it’s superimposed, you are not recognizing your total being.”

Since her success came late, wasn’t Nevelson ever discouraged? “For about 40 years I wanted to jump out my window in New York. But if you’re going to have a baby, it’s glorious when the baby is born. In the meantime, you have labor pains. From the time I showed my first drawing, the critics and my teachers were magnificent. They fed my courage. My first dealer told me years ago that the only reason I didn’t sell was that America was too young, vulgar, too much new money. They weren’t going to buy my old wood from the street.

“There hasn’t been a surprise in my life. In my darkest moments, I was never not with what I was doing. My life was important to me—I certainly expected it to be what it is. The forms may have changed, but the root of my being about creativity has not. I recognized the energies, my own ability, and they added up to what I projected. I built my life, and it fits me like a glove.

“By the time you reach maturity, you know what you’re doing. The adulation is lovely, but they don’t give me anything.

“Now, when I get depressed, I say to myself, ‘Look, you son of a bitch, you got as much money as you need. You like your work, so why are you depressed?’ So I go on a drunk, feel better and then I rest afterwards.”

Nevelson lives and works on Spring Street in New York, in the Little Italy section of New York City. The Nevelson quarters consist of three buildings—a five-story former sanitarium, a four-story building and a garage that is a studio. In 1966, Nevelson sold some furniture and put the rest on the street for the garbage collector. Arnold Glimcher, her dealer, wrote that visiting the house after 1967 was a “very different experience, more like visiting a monastery than a garden in the moonlight.”

“I use the houses as if they were on wheels,” Nevelson said. “None of the furniture of static. I have picnic tables that can be folded, chairs that can be stacked. There are no couches. I change the floors on which I work. My space cannot be ordered. The works surrounds me on the floor.

“I get up very early, at about 3 A.M. I don’t sleep much. I read and usually go to bed early. I once asked Josef Albers if he was a great reader and he said, ‘If I wanted to read, I’d write my own book.’ That’s my thought, too. At 3 A.M., I’m already planning and plotting with the work, and if I’m not, I’m very unhappy. I don’t want hobbies, slobbies. I can’t even stand movies.

“In my old age, I’m beginning to be self-centered. I get a kick out of myself. I was once captain of the high school basketball team in Rockland, and I just like to see every now and then if it still works. So I can be lying in the tub, and I pitch a cigarette at the toilet and I never miss.”

What is the quality she most admires in people? “I admire in any human the courage to fulfill their lives. Einstein, Picasso are among the peaks of humanity. When I think of what went through that mind to invent Cubism. I could have met Picasso in 1931. Some artists wanted to take me, but, believe it or not, I was shy. I didn’t have the courage to intrude on him. I couldn’t confront him in 1931, and five years ago I felt it was too late. I don’t have to meet people to have regard for them. Almost all of my adult life I have known and met prominent people. Artists who are my close friends are a natural. I didn’t go out of my way to meet them. I don’t worship people. I respect some of them.”

Soon after graduating from high school, she married Charles S. Nevelson. A son, Mike, now a sculptor, was born in 1922. A few years later the marriage broke up.

“The unfortunate thing is to fall in love. I got married when I was young. I met my husband when I was 17. I got divorced, but I always had someone around. I think true love is a dedication. For me, it would have been a full-time job, and my dedication is art. I would have hated to live on this earth and not to explore it. I could not have gotten married and stayed that way. I’m too curious.

“I think every artist is masochistic. You know that you are trying to be one of the most difficult things in the world. I suppose I’ve never yet stopped digging daily for what life is all about.”

Nor has she stopped digging artistically, either. She is turning to new materials for her collages (“They’ve gladdened me in a way. They are like the flowering of a plant.”) and to a new color for her sculpture.

When asked if these were the best years of her life, she paused and said, “Yes and no. On the one hand, it’s the best. On the other hand, when you get to be 75, it’s the worst. Lipchitz, during the last years of his life, said that just to get up in the morning and know that you’re alive is terrific. I think that’s a tragedy. It isn’t the abundance of life. I didn’t care if I had all the comforts but I wanted to fulfill my potential. Well, I’ve lived as if there was no tomorrow. I do feel that I haven’t had the last say in my work, and when that’s done, that’s it.”

[ad_2]

Source link