[ad_1]

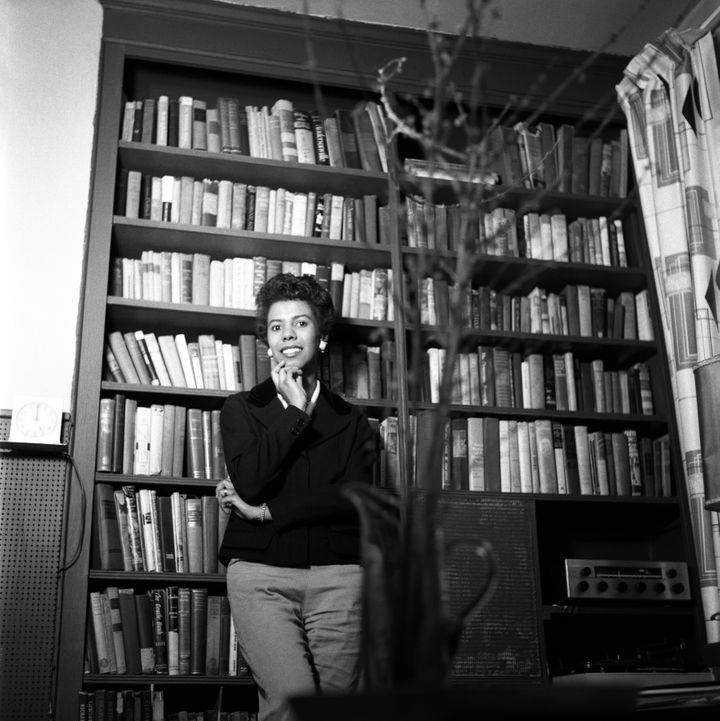

Lorraine Hansberry was a master scribe. She used her writing to redefine difference. The award-winning playwright — whose 90th birthday would have been this week — first captured the public eye during the civil rights movement.

Hansberry was perhaps best known for the American classic “A Raisin in the Sun,” so named after a verse from a Langston Hughes poem. But it’s one of her last plays, “Les Blancs” (“The Whites”), that strikes the most powerful and resonant chord at this current moment.

A visceral and cerebral response to the injustices Hansberry confronted in the 1960s, “Les Blancs” debuted on Broadway on Nov. 15, 1970, and ran through the end of the year. The cast was legendary, with leading men James Earl Jones and Earle Hyman.

The play was nominated for two Tony Awards (best costume design and best performance by a featured actress in a play), but Hansberry never had a chance to see it reach production. She died of cancer five years prior to its Broadway run, at the age of 34. Yet 50 years later, Hansberry’s “Les Blancs” remains a radical testament to her global vision and prescience.

Set in the fictional country of Zatembe, the story follows Tshembe Matoseh (Jones), who returns home from London for his father’s funeral. The prodigal son soon discovers his countrymen embattled in a struggle for independence, while his brother Abioseh (Hyman) has forsaken “his African ways” in order to assimilate and join the Catholic priesthood.

Hansberry unlocked the central problem after the U.S. premiere of French writer Jean Genet’s play “Les Negres” (“The Blacks”) in May 1960. (Jones also starred in the original cast of that play.) She felt that Genet propagated a hollow view of prejudice and exoticized Blackness for a white audience. With a studied paintbrush, she turned the image of the Other back on him, understanding intuitively that “Les Negres” was about “Les Blancs.”

This is the same observation Toni Morrison made in “Playing in the Dark” (1992), about how “the fabrication of an Africanist persona is reflexive,” merely used as an aesthetic device to maintain dominance in the sacrifice of meaningful language. Compelled to correct Genet’s omissions, Hansberry revealed how white guilt and romanticism reinforce colonialism and its present-day legacy: racism, capitalism, neoliberalism.

For her protagonist, Tshembe, Hansberry spun a complex web of internal and external conflict. Just as Tshembe struggles to get his bearings, intrepid American reporter Charlie Morris intrudes on his homecoming. Morris has come to visit the Mission in Tshembe’s village, hoping to meet the Reverend and see how Western intervention can save a poor and feuding African populace. He tries to make friends.

“Mr. Morris, I am touched, truly. But, tell me, when you passed through Zatembe, did you just happen to see the hills there and the scars in them? The great gashes from whence came the silver, gold, diamonds, cobalt, tungsten?”

The foreigner chooses not to follow the African on his train of thought.

“To me, you are no more ‘the Blacks’ than I am ‘the Whites’,” Morris tries to convince himself.

“… I am myself,” Tshembe corrects him. “You are a tide … a receding tide.”

As an Ethiopian-American, I feel a kinship with Tshembe as much as Hansberry. I have seen and met many Mr. Morrises before. Insert white American or European with public health, development, nonprofit experience. No matter how well-meaning, he cannot see himself. Though he does not mean to offend, his very presence in Africa reeks of its entitlement, of consequences, which he is unwilling to acknowledge. Instead, he chooses to inspect the Blacks and the particular facts of his geography, with himself positioned at the center of the map.

But this world does not belong to him. Like Genet, Morris has a lack of self-awareness that represents deep desperation to absolve himself of any accountability. He refuses to face the truth, until Dr. Willy DeKoven, another white man, holds a mirror up to him. “Mr. Morris, the struggle here has not been to push the African into the 20th century — but at all costs to keep him away from it! … That is part of what is happening here. … The other part has to do with the death of a fantasy.”

Hansberry’s words have the effect of a scalpel on a festering tumor. She was intersectional before the term was in vogue. As a Black feminist writer in the ’60s, she was a warrior, no doubt inspired by the radical politics of that era. The fervor is evident by the fire from her pen as she skillfully articulated social tensions and economic disparities that still exist today.

In her formative years, Hansberry was exposed to Pan-Africanism and transnational solidarity. Her uncle, William Leo Hansberry, was a renowned scholar in African antiquity. His students included Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria, who would each return to lead their newly independent countries. In the early ’50s, working as a reporter and associate editor for Freedom in New York, Hansberry was influenced by international figures such as Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois and W. Alphaeus Hunton, director of the Council on African Affairs.

During one of her earliest speaking engagements, Hansberry boldly expressed that “the ultimate destiny and aspirations of the African peoples and 20 million American Negroes are inextricably and magnificently bound up together forever.” This divine connection is crystallized and charged throughout “Les Blancs.” Especially in the final act.

The fate of the future depends on the Blacks.

The play builds toward a crescendo, when Peter, one of Tshembe’s own people whose real name is Ntali, calls on him to act.

Peter: “You understand, we are determined to rule? By whatever means necessary …”

Tshembe echoes his urgency with new emphasis: “By whatever means necessary … !”

As Attallah Shabazz clarified in “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” that particular sentiment has often been misinterpreted. Rather than raise arms, her father was calling for reclamation, equity through cultural and social reconstruction. And that’s where Hansberry leaves us in the closing scenes of “Les Blancs”: on the precipice of revolution.

In a critical background on Hansberry’s last works, Robert Nemiroff, her husband and literary executor, noted that she believed “Les Blancs” had the potential to be her most important play. The story’s moral imperative planted the stakes “not just here in America, not even in Africa, but on the world scale,” Nemiroff wrote. She was ready “to confront head-on the impending crisis between the capitalist West and the Third World.” Hansberry’s perspective created a holistic, humanist and historical portrait of resistance, which shifted the narrative lens away from America to interrogate global systems of oppression and the myth of the Dark Continent.

While battling cancer, Hansberry spent years writing and rewriting the script for “Les Blancs,” editing and redeveloping it during hospital visits as her health continued to decline. She left behind several drafts, which Nemiroff later completed on her behalf, based on the structure she detailed before her death. It is the only Hansberry play that he adapted to completion.

It’s also particularly poignant that, despite the prominence of strong-willed men, arguably, the most powerful figure in “Les Blancs” is Woman. She is a nameless symbol of Tshembe’s conscience, who clutches a spear and appears in his most anguished moments. Woman speaks with movement and the sound of drums. She is angry, unafraid and determined to be free. By whatever means necessary. In Woman’s shadow, Hansberry is manifested more than half a century after her death. Her voice is a song, a war cry in the distance, drawing closer, awakening the next reader.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link