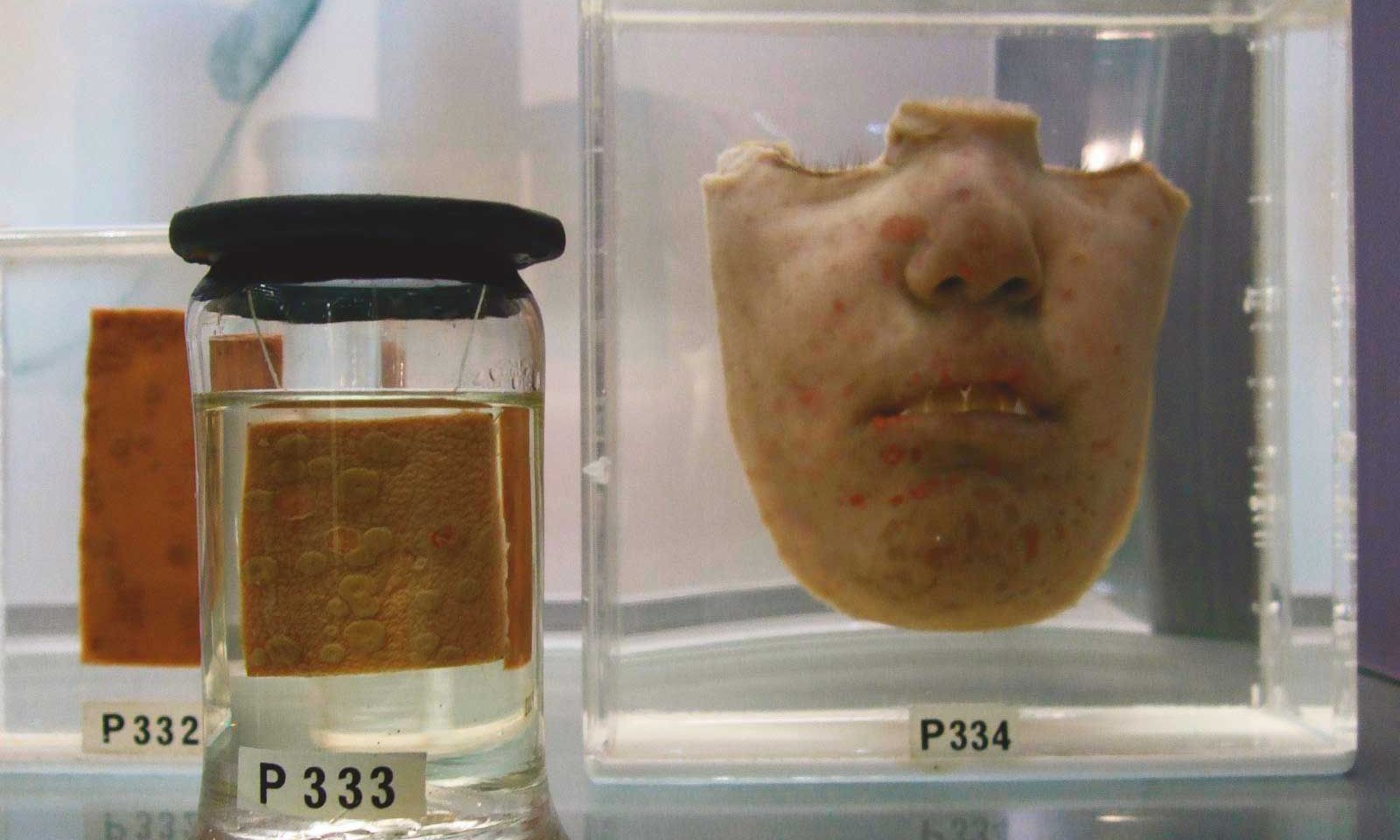

Human remains at the newly reopened Hunterian Museum in London

Courtesy Hunterian Museum. Photo © Stefan Schäfer

“There’s a certain way of displaying human remains that we’re mindful of, I think,” says Dawn Kemp, director of Museums and Archives at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. “It is a deep respect to those named and unnamed and whose bodies have been used to further medical knowledge and understanding.”

Kemp is talking about the Hunterian Museum, located in the Royal College of Surgeons’ (RCS) building in London’s Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which reopens on 16 May after a five-year redevelopment. Named after 18th-century surgeon John Hunter—whose fellow-physician brother William gave his name to the similarly titled Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery in Glasgow—the museum contains Hunter’s celebrated collection of anatomical and pathological specimens from human and animal sources, currently numbering around 3,500 items, the remains of Hunter’s original 14,000-strong collection, much of which was destroyed in a German bombing raid during The Blitz of London in 1940.

The £100m redevelopment, overseen by architects HawkinsBrown, has retained the museum’s Grade II* listed façade but rebuilt the rest of the site. As a result, the exhibition galleries of the RCS have been moved to the ground floor in order to increase public access and awareness—but this has meant the destruction of the famous Crystal Gallery.

Kemp is keen to point out that the RCS does not own Hunter’s collection; it was bought by the government in 1799 and has been administered since by its own trustees. The museum also

holds other more recent collections: teeth, bones, ancient remains, and a wide variety of surgical and medical tools (ranging from items developed by medical pioneers such as the British surgeon Joseph Lister to robot devices used in today’s surgery).

The reshaping of the display was governed by the general public’s increasing interest in, and awareness of, scientific and medical innovation, says Kemp. “Originally, the collection was for medical people to learn from. But take, for example, the DNA helix—that’s mainstream public knowledge now, whereas, in the 1950s, it would have been high-end research. We are really committed to public engagement and helping people know and understand more about the history of medicine.”

That the museum’s display of human remains is a highly charged topic is reflected in the furore surrounding one of Hunter’s most well-known specimens: the skeleton of Charles Byrne—or the ‘Irish Giant’—who grew to at least seven feet and seven inches tall before his death in 1783. Hunter purchased Byrne’s corpse and his skeleton has now been on public display for over two centuries. But after a vocal campaign (which included the late writer Hilary Mantel, whose 1998 novel The Giant, O’Brien is about Byrne and Hunter), the trustees have decided to remove the remains from display when the Hunterian reopens, showing instead a portrait of Hunter by Sir Joshua Reynolds in which the skeleton is partly visible. The issue of consent is key: by all accounts, Byrne requested a sea burial.

The museum takes its name from the 18th-century surgeon John Hunter, painted here by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1785 with the ‘Irish Giant’

© Hunterian Museum; Royal College of Surgeons of England

Kemp refers to a statement issued by the trustees, which observes “the sensitivities and differing views surrounding the display and retention of Charles Byrne’s skeleton”. While the skeleton will be removed from display, “it will still be available for bona fide medical research into the condition of pituitary acromegaly and gigantism”. Kemp stresses this is the trustees’ decision to make, not the Royal College’s. “It is absolutely about this reflection—the change and mindfulness of sensitivities,” she says. But Byrne still isn’t getting his sea burial, it seems.

The row over Byrne reflects a wider dispute over the institutional collection and retention of human remains. The Human Tissue Act 2004 specifies that only body parts over 100 years old can be retained without permission. The act was introduced after the Alder Hey scandal in 1999, in which it was discovered that large numbers of organs of deceased children had been kept in storage at the Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool, UK. As well as Byrne, attention has also focused on the remains of indigenous peoples, particularly from Australia and New Zealand, that were retained in the RCS collection. While the RCS has not commented publicly on the subject, a PhD submitted in 2017 by Oxford University student Sarah Morton outlines the repatriation of RCS-held remains to Australia, New Zealand and Hawaii from 2001 onwards. In the same period, the RCS released the skull of notorious 19th-century murderer William Corder for cremation, and autopsied the remains of the victims of the Belsen concentration camp for burial in a Jewish cemetery.

Less controversially, Kemp is keen to talk up the riches of the RCS’s art collection, which, she says, spans everything from treatises by 14th-century surgical pioneer John of Arderne up to 21st-century 3D body imaging. She is particularly effusive on the subject of Slade fine art professor (and former surgeon) Henry Tonks’s moving drawings of First World War casualties undergoing pioneering plastic surgery. “Artists are often the unsung heroes of the developments in learning of human anatomy,” she says.

But, for Kemp, the Hunterian is ultimately about helping people to become more conscious of themselves. “It’s not just about surgery. It’s about helping people gain an understanding of the human body. If we can do that, then we can better care for our own wellbeing,” she says.