[ad_1]

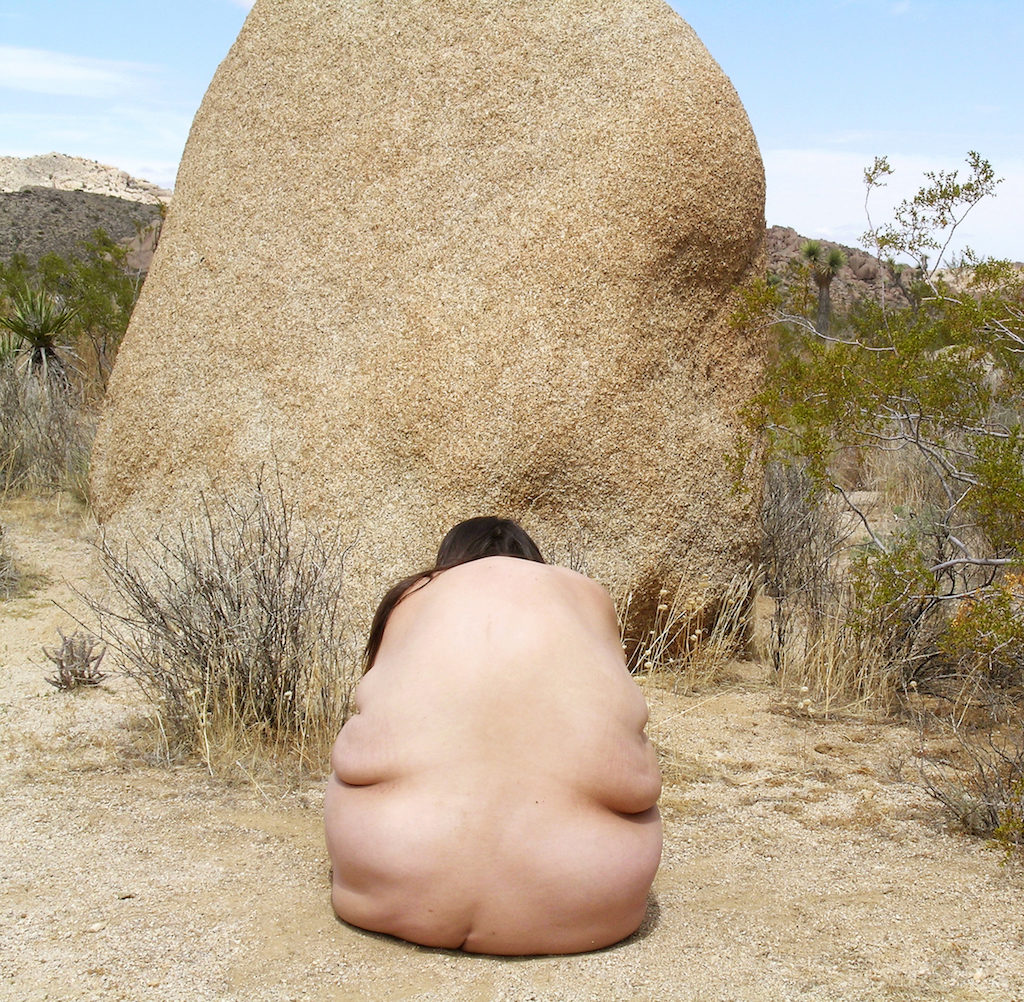

Laura Aguilar, Grounded, 2006, inkjet print.

©LAURA AGUILAR/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND THE UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER

Chicana photographer Laura Aguilar, whose stunning retrospective at the Vincent Price Museum of Art in Monterrey Park, California, now on view at the Frost Art Museum at Florida International University in Miami, made her one of the breakout stars of the Getty Foundation’s recent Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, has died. She was 58.

Aguilar’s powerful, quietly beautiful photographs explored the lived realities of members of various marginalized groups, including women, lesbians, Latinas, the working class, overweight people, and those with learning disabilities. Long under-recognized by mainstream institutions, her work had a sudden resurgence in popularity last year thanks to her traveling retrospective and the inclusion of her work in several group exhibitions across the PST program, including “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.,” which debuted at the MOCA Pacific Design Center and ONE Gallery and is currently traveling.

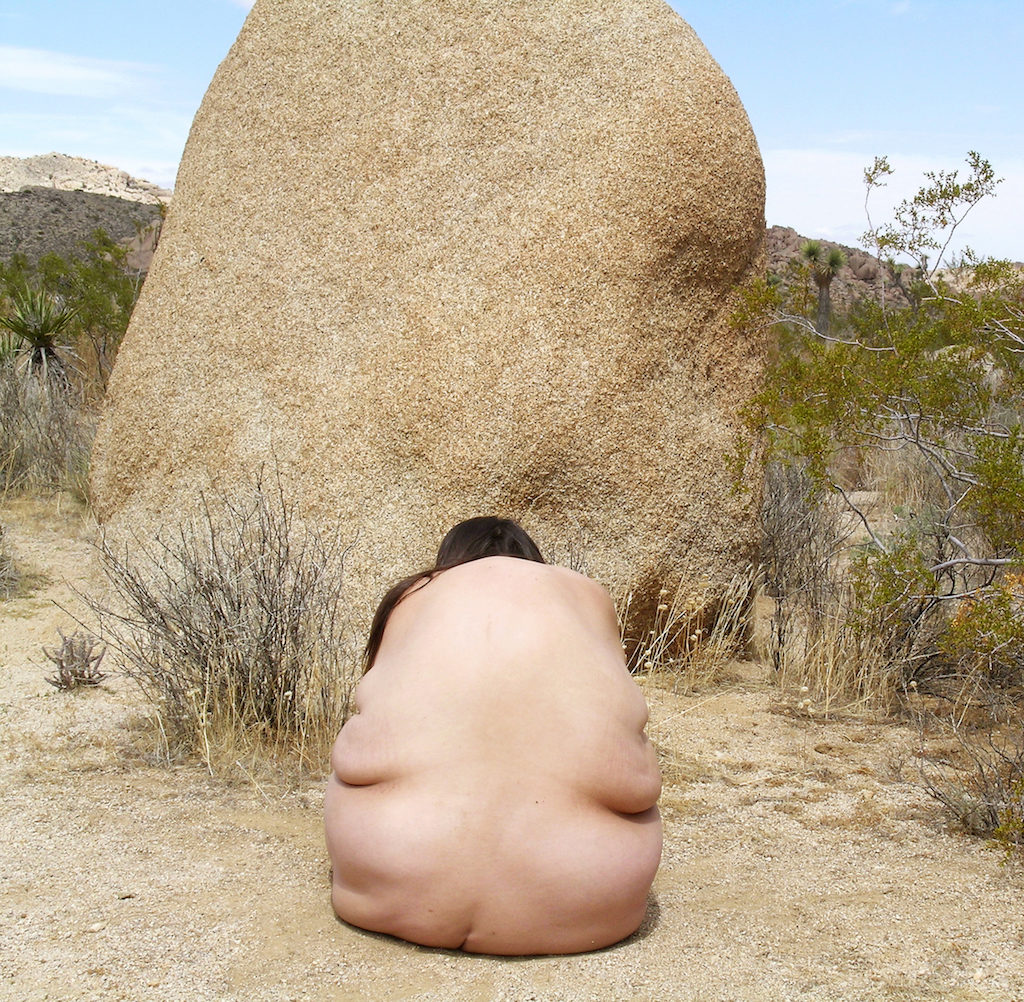

Her most well-known work, a triptych of black-and-white photographs Three Eagles Flying (1990), is emblematic of her practice. In its center panel, a bare-chested woman (Aguilar herself) is shown with an American flag wrapped around her waist, a Mexican flag completely covering her face, and her hands bound by a thick rope, which courses up to her neck, almost strangling her. The left panel shows a vertically hung American flag; the right, a Mexican one. Aguilar appears caught between two worlds, attempting to negotiate a space for herself as an American citizen with Mexican heritage, treated as a foreigner in her homeland. Since the ’90s, the work has helped visualize a sense of double consciousness felt by many in the Chicanx community, in particular by Chicanas, as it shows the struggles its members face as people who understand themselves as being both American and Mexican, but feel as though they are unwelcome in either country.

Laura Aguilar, Three Eagles Flying, 1990, three inkjet prints.

©LAURA AGUILAR/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND THE UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER

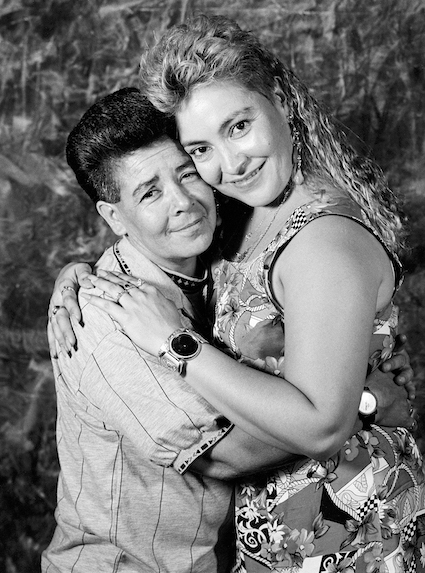

In her series “Latina Lesbians” (1986–90), she photographed gay Latina women, with her subjects gazing directly into the camera’s view; below the images, each of which is mounted on white paper, are captions (some include spelling errors) that detail these women’s opinions of what it means to be a woman, a lesbian, and/or a Latina. One reads, in part, “Names, the Spanish language, the color of skin, other people, places and things have all affected my identity. . . . Someone once said to me, ‘You are what you identity yourself to be.’ We all have choices and make them. I choose to be, among other things, a Chicana.” By providing these captions, Aguilar allowed her subjects to describe themselves, to talk about their identities in their own words, on their own terms.

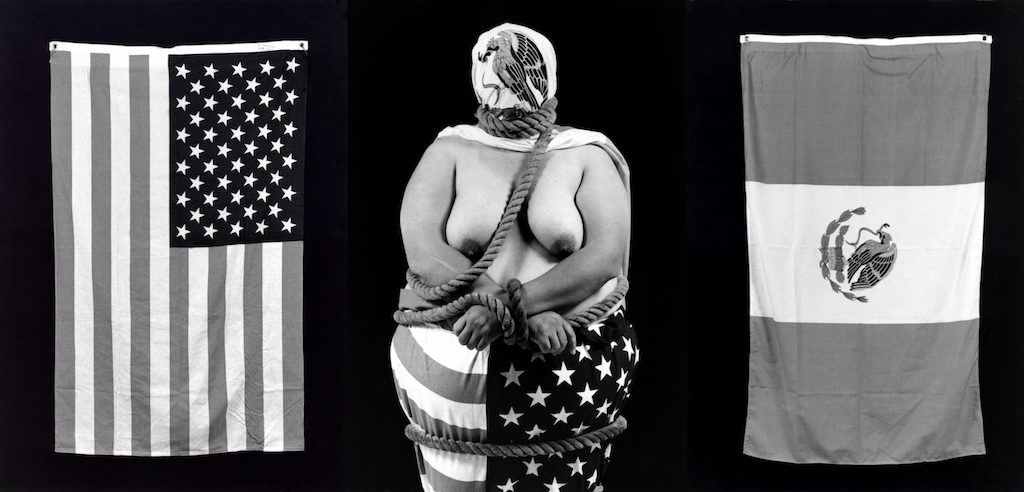

Laura Aguilar, Plush Pony #15, 1992, gelatin silver print.

©LAURA AGUILAR/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND THE UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER

These works were a precursor to a second series, “Plush Pony” (1992), in which Aguilar set up her camera in a bar mostly frequented by working-class lesbians on Los Angeles’s Eastside area. In the works, which she shot as studio portraits, the subjects—both powerful and empowered in Aguilar’s series—stare directly at the camera. In the same way that Nan Goldin and Peter Hujar turned their lenses on New York’s Downtown scene during the late ’80s and early ’90s, in an attempt to hold on to memories of places and people that were quickly and suddenly being lost to time, Aguilar captured a cultural zeitgeist—one that was specifically queer, Latina, and working-class, and one that was, because of all those factors, often overlooked.

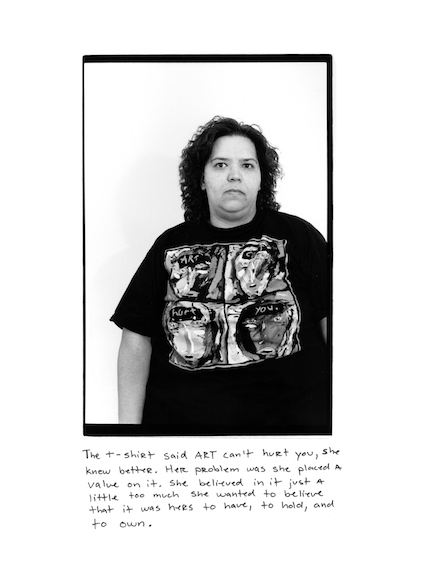

But Aguilar’s work didn’t simply accept marginalization as a given for her subjects and for herself; she wanted to upend it, to make space for those who had been pushed aside, into the closet, or out of the mainstream. In one work, Aguilar photographed herself standing in front of a wall that says “Gallery”; she holds up a cardboard sign that reads “Artist Will Work For Axcess.” Another work, consisting of four photographs and titled Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt, shows Aguilar holding a pistol to her mouth; a caption beneath one of the pictures notes, “If you’re a person of color and take pride in yourself and your culture, you use your art to give a voice, to show the positive. So how do the bridges get built if the doors are closed to your voice and your vision?”

Aguilar produced several series in which she photographed herself—often alone, sometimes with other women—nude in natural settings. In these works her body melds with the landscapes, from arid deserts to lush forests. In the desertscapes her form often appears to be a large rock at first glance. Most viewers will quickly notice that Aguilar is overweight, and these photographs daringly force viewers to confront her body, which is often on full display. They ask the viewer to intimately appreciate her body for its beauty, as well as all the ponds, rock formations, and dried leaves surrounding it.

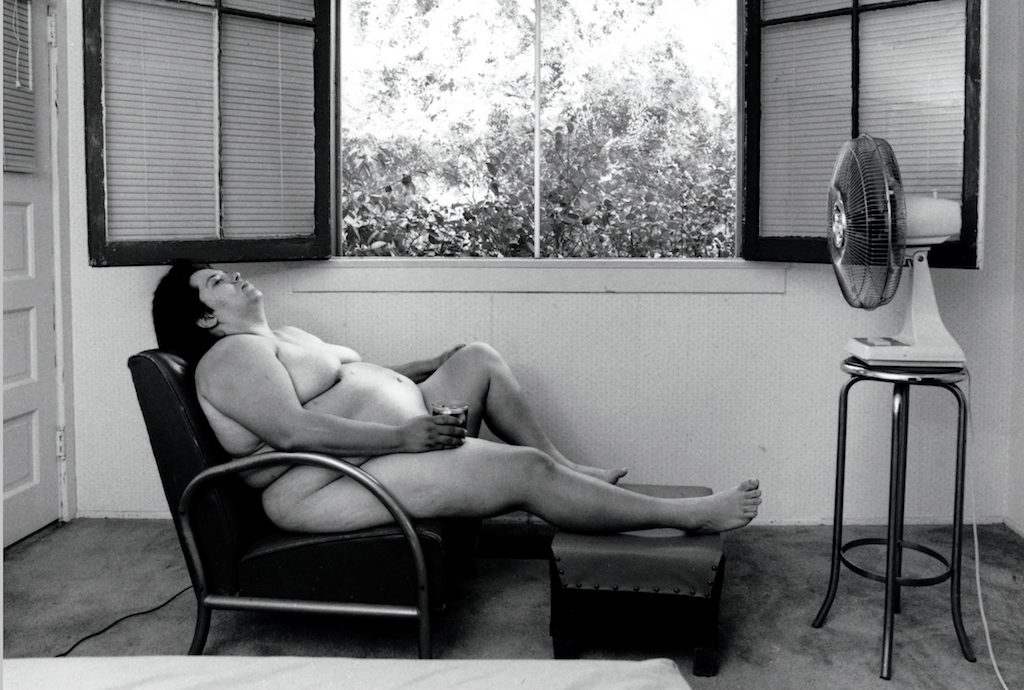

Laura Aguilar, In Sandy’s Room, 1989, gelatin silver print.

©LAURA AGUILAR/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND THE UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER

Many works, Three Flying Eagles among them, feature Aguilar using her nude body as a tool to interrogate standards of beauty. In Sandy’s Room (1989) shows Aguilar reclining on a chair, sans clothes, trying to cool off on a sweltering day as a fan blows in front of her. (An image of the work was briefly shown in the recent Amazon television series I Love Dick, during a scene in which a curator envisions a more inclusive art-historical canon that places less of an emphasis on white, heterosexual, male artists.) This work, like all her nudes, explores the way we conceive of bodies with curves.

Laura Aguilar, Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt (Part A), 1993, gelatin silver print.

©LAURA AGUILAR/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND THE UCLA CHICANO STUDIES RESEARCH CENTER

Laura Aguilar was born in 1959 in San Gabriel, California, in a region just east of the L.A. city limits that has large Chicanx, Asian American, and black populations. The diverse group of people she encountered growing up there informed much of her work. She was born with auditory dyslexia, and attributed her introduction to photography to her brother, John. She briefly attended East Los Angeles College in the late 1970s, though she considered herself a self-taught photographer. Even though her time at ELAC didn’t cement her career as a professional artist, it gave her entry to various vibrant Eastside Chicanx communities, including working-class groups, queer communities, and various art worlds that existed outside the mainstream. All of these communities would become the subjects of her work.

In 1993, Aguilar’s work was included in the Venice Biennale’s “Aperto” section, a program dedicated to emerging artists. Her photographs were positioned alongside work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Matthew Barney, Sadie Benning, Nari Ward, Andres Serrano, Kiki Smith, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Damien Hirst, and John Currin, among many others. Though many of the artists’ reputations (and markets) survived the mixed criticism of the show, Aguilar’s did not. Her appearances at various PST shows last year put her back on the map for many in the mainstream art world, even though her work has, for the past few decades, been essential to the Chicanx community, and in academic circles, where it is hailed for its pioneering intersectional feminism. Her retrospective at VPAM, which was highly praised and considered by many to be one of PST’s greatest surprises, was itself a homecoming, as the museum is part of the ELAC campus.

“Laura Aguilar’s work speaks to so many people,” Pilar Tompkins Rivas, the director of VPAM, said in an email. “Her work is personal, political, celebratory, and difficult, all at the same time. She speaks about a journey of self-acceptance—she speaks about visibility and difference, and the nature of life’s challenges.”

Despite having spent years without widespread critical acclaim, Aguilar remained confident and continued producing powerful work. Maybe it’s best to remember Aguilar by the ways she depicted herself. In one work from the “Latina Lesbians” series, she’s seen smiling and wearing a cowboy hat, standing in front of a reproduction of a Frida Kahlo self-portrait. Beneath her image, a caption reads, “Im not comfortable with the word Lesbian but as each day go’s by I’m more and more comfortable with the word LAURA. I know some people see me as very child like, naive. Maybe so. I am. But I will be damned if I let this part of me die!”

[ad_2]

Source link