[ad_1]

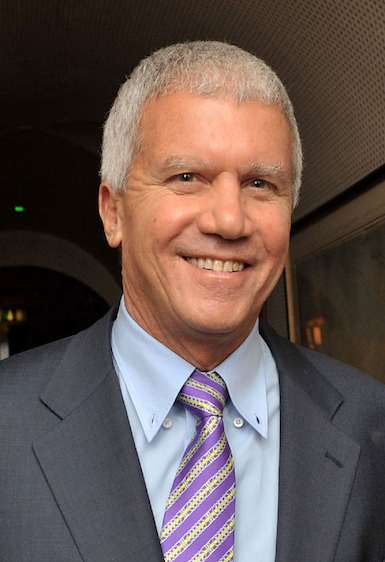

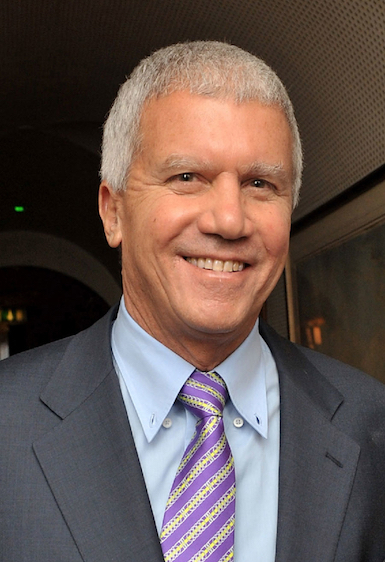

Gagosian.

COURTESY GAGOSIAN GALLERY

After losing a bidding war at Christie’s in New York last night over a late Willem de Kooning painting, mega-dealer Larry Gagosian took the stage this morning with Edward Dolman, the CEO of Phillips, at the Wall Street Journal’s “The Future of Everything” Festival at Spring Studios in TriBeCa. The conversation, moderated by the Journal‘s art-market reporter, Kelly Crow (who was also on hand at last night’s auction), began with talk about the star lot from the collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller: Pablo Picasso’s Fillette a la corbeille fleurie (1905), which Christie’s sold on Tuesday night for $115.1 after uneventful bidding. Crow noted that, when the piece was hammered, there was no applause from the crowd. Why?

“Let’s be rational,” said Dolman, “and that’s hard to be in our industry. . . . Christie’s obviously found a guarantor.”

Gagosian and Dolman both agreed that the decision by Christie’s to raise the estimate from $70 million to $100 million leading up to the auction may also have influenced the proceedings. “You get jaded with these numbers,” Gagosian said. “It takes more to get people to clap. You have to have some bidding.”

The conversation then shifted to the theme of the event: the future of the art market. After the sale last fall of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi (ca. 1500) for $450.3 million and the frequent headlines about new auction records, it has become irresistible for some to speculate about what will be the first artwork to sell for $1 billion. Crow asked the two men whose work might reach that mark.

If he knew which painting would make it, “I’d want to buy it now,” Gagosian joked, before predicting that Vincent van Gogh might be able to win that trophy. Dolman went with Leonardo and Picasso. “I often think that what holds people back from investing this much cash in pictures is a fear of being stupid,” Dolman said. “So I think these new records make people feel better about spending if something great comes to the market.”

The juiciest part of the talk came when the conversation turned to the much-discussed issue of how to keep smaller galleries in business. (David Zwirner, for instance, recently suggested that mega-galleries ought to help out the little guys, perhaps by paying higher fees for art fair booths, and Postmasters began accepting funding through the online Patreon program.)

Speaking about the gallery industry generally, Gagosian said, “I think it’s a pretty good system from my perspective,” which warranted some hearty laughter from the audience.

Expanding on his point, Gagosian explained, “In a larger sense, I think it’s a unique economy. The less you fiddle with it, the healthier it’ll be. As far as the question of smaller galleries falling by the wayside, I’ve seen these cycles. I’ve been an art dealer for 40 years. It’s just a cyclical thing.”

Gagosian argued that a laissez-faire gallery industry makes sense because there is an abundance of investors willing to give funds to new galleries. “It’s very easy to open a gallery,” he said. “To open a small gallery—which I did, I started with nothing—it doesn’t take a ton of capital, and you can find insane capital to open a bootstrap gallery. So the barrier to entry is relatively low, compared to other businesses. . . . This encourages people to take a shot. They may not be cut out to run a gallery, but they’re inspired to try.”

[ad_2]

Source link