[ad_1]

Installation view of “Kurt Kauper: Women,” 2018, at Almine Rech Gallery, New York.

MATT KROENING/©KURT KAUPER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ALMINE RECH GALLERY

As Architectural Digest reminded its readers in November, art dealer Jeffrey Deitch’s Los Angeles home contains an artwork-as-in-joke: the house once belonged to actor Cary Grant, and hanging prominently on Deitch’s living room wall is artist Kurt Kauper’s life-size painting of the actor striding down one of the house’s red-tiled hallways, unapologetically nude. In 2003, Deitch showed Kauper’s then brand-new series of nude Grant paintings in his New York gallery. Four years later, he showed the artist’s series of naked former hockey players—the Bruins’s Bobby Orr and Derek Sanderson—which, like the Grant paintings, Kauper had done based on photographs. Reviewing the show for the New York Times, Karen Rosenberg wrote that the paintings “work . . . as an erotic and personal tribute, one that draws on the artist’s childhood in a Bruins-worshiping Boston suburb; the neo-Classical figuration of Jacques-Louis David; and the overt sensuality of pre-Stonewall ‘athletic’ films.”

Kauper’s recent exhibition at Almine Rech gallery on Manhattan’s Upper East Side saw him exploring territory that, since he began painting over 30 years ago, he had basically ruled out: the female nude. Lined up on one wall were three larger-than-life-size paintings of female nudes presiding over the room like daunting caryatids. They are painted against flat minimalist grounds, each of a vaguely indeterminate color, one pinkish, another greenish, and the third mustard-tone. The women’s feet are planted firmly on the ground in such a way that they draw attention to the figures they support. The effect is slightly strange given their apparent strength and assertiveness as well as androgyny—the feet are nearly the most sexually ambiguous aspect of the solid looking women, although the bodies’ musculature and strong forward stance underscore the sense of gender ambiguity.

While over the last few years Kauper kept a low public profile as he sought out new directions for his paintings, the renewed interest in figuration today and the subtly anomalous style he arrived at has brought his work back into the spotlight.

Where Kauper’s earlier works shocked with their content, these do so with their unabashed impenetrability, their subjects’ statuesque, soldier-like postures, and their gender-challenging demeanors—or what Kauper prefers to call their “neutrality.”

For Kauper, to create the “Neutral” is to create an image or idea that falls between genres, definitions, sexuality, perceptibility—that is, ultimately, “indeterminate.” The philosopher Roland Barthes was the source of the term, having stated, “I define the Neutral as that which outplays (déjoue) the paradigm, or rather I call Neutral everything that baffles the paradigm.”

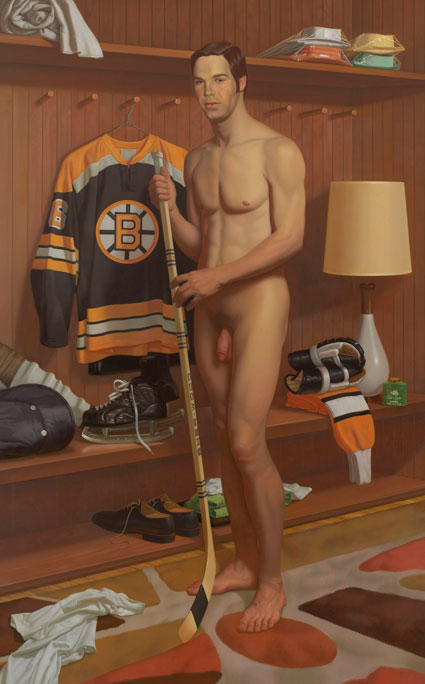

Kurt Kauper, Derek, 2005, oil on birch panel.

©KURT KAUPER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ALMINE RECH GALLERY

Kauper, 52, studied at Boston University, where, he said, there was a strong figurative tradition. “I sought out the version of traditional training, which wasn’t that traditional,” he said. “I studied with a group of teachers who were really German Expressionists, or they were influenced by German Expressionism. But I remember them telling me things like, ‘All art died with Matisse.’ . . . And they also used to say things like, ‘No matter whether you’re looking at Giotto or Picasso, all that matters is the movement of volumes through space.’ So they thought they could understand art purely in terms of a kind of single, formal lineage that ran through the early Renaissance to Picasso. That kind of thinking just seemed absurd to me. . . . And so artists who ignored the formal aspects of art, but emphasized the conceptual, became really important to me.”

He met one of those artists who emphasized the conceptual when he attended grad school at UCLA, where he became close friends with Charles Ray, the figurative, hyper-real, near-surrealist sculptor and installation artist. Both artists are masters of the uncanny.

Reflecting on his own evolution and artistic influences, Kauper acknowledged Ed Ruscha and Ray (“one of the very best artists definitely of his generation”). “But also,” he said, “when I was a teenager, my favorite artists were people like Ingres, who still is my favorite.”

“What Kauper is doing in painting,” observed Jeffrey Deitch, “is essentially what Ray is doing in sculpture. One of the special skills that Kurt has is to create the illusion of weight with these figures. And in addition to a fusion of conceptualism and figuration, there’s also a great fusion of abstraction and figuration.”

“Kurt,” he added, “is like a novelist inventing character. These figures are as close to abstraction as you can get with a perfectly rendered figure—they’re deliberately drained of personality; they’re formal; and they do reject female power and strength, but it’s very hard, I don’t see any psychological analysis of these figures, it’s much more abstract.”

Deitch has called Kauper “the most contemporary figure painter. His pictures, while figurative, do not engage in storytelling,” he pointed out. Rather, “the indeterminate nature of his images is that they are ‘constructed fragments’ and therefore are open to interpretation.”

Kauper said he did not want to paint the female nude because “it was such well-covered territory. When I first came out of graduate school, there was a very well-publicized return to figuration, and then, many of those most prominent artists were painting the female nude—[John] Currin, [Lisa] Yuskavage, Will Cotton, [and] Martin Eder.” He added, “If you define that very broadly, people like Wangechi Mutu were also dealing with the female nude. I didn’t want to fall into the trap of going back to a kind of over-conventional representation of desire.”

A couple years after completing his hockey players, he decided he would break his own rule.

“When I started thinking about the fact that I had set up a prohibition, I wondered if it would be interesting for me to question that prohibition,” he said. “I thought, if I’m going to paint the female nude, I want to paint the female nude that doesn’t go back to a kind of conventional representation of objectified desire. . . . Not that I don’t love many artists who do that, and you know Currin is probably my favorite painter of that generation, but I just didn’t want to go there.”

He wanted to tap into a tradition that attempts to “undermine” that objectified desire. That’s probably where the concept of the “neutral came in.”

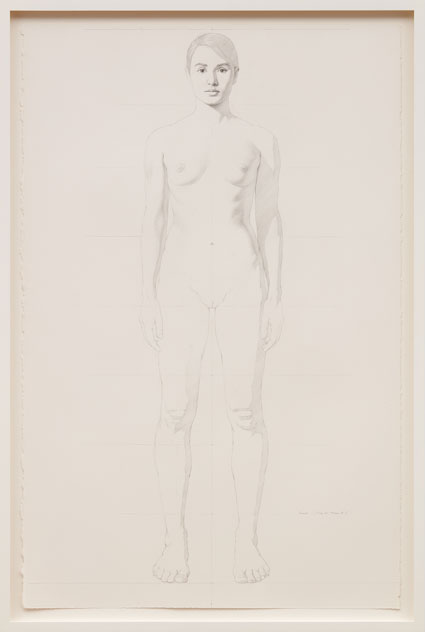

Kurt Kauper, Study for Woman 5, 2017, graphite on paper.

MATT KROENING/©KURT KAUPER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ALMINE RECH GALLERY

Settling on poses was not an easy proposition. He started out with a female nude with her hands on her hips. But “even that very minor gesture contained too much,” he said. “It sort of directed the meaning too much. So I eliminated that. And I just became interested in these absolutely straightforward, straight-on figures as a way of seeing if I could find a different approach to the female nude,” one that relates to the viewer differently from what we’re familiar with.

He completed the first of the paintings in 2015. (He’d started it in 2010 and then “other things, both personal and professional,” he said, interfered.) He started the rest a few months later. At the end of that year, Deitch and Larry Gagosian included Kauper’s hockey player paintings in their exhibition “Unrealism” in Miami’s Moore Building during Art Basel Miami Beach. Among those who saw them were art dealer Almine Rech, and her husband Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, grandson of Pablo. Soon after, Rech contacted Kauper about a show.

“I’ve found that people who have a deep background in historical art, who aren’t part of the New York trend surfer set, can really relate to Kurt’s work,” Deitch said, “so it’s quite significant that the dealers Almine and Bernard, with their background, were intrigued by this.”

Speaking of backgrounds . . . inspiration for the mustard-tone setting of this nude may have in part come from an unlikely source, the painter of race horses George Stubbs. Deitch recalled Kauper telling him that he’d been inspired by Stubbs’s painting Whistlejacket (1762).

“It’s the way Kurt has done it,” Deitch said. “I’ve never seen anything like this, where he’s channeling the tradition of painting race horses. That makes the appreciation of his works so much more interesting. Because they are in dialogue with contemporary issues, very current gender issues, a very very contemporary discussion, but they go back to issues of how to construct a painting that goes back 250 years.”

When I asked Kauper about this, he mentioned Velázquez and Eakins, but admitted there is something special about Whistlejacket: “The background is such a deliberate elimination of narrative.”

“I’ve recently been realizing that, in a way, I’m a formalist,” he continued, “at least in the sense that what motivates me to make my work is always existing form. And then the challenge is how to extend the ability of that form to participate in contemporary discourse.”

[ad_2]

Source link