[ad_1]

Vincent van Gogh’s life and work have long been subjects of fascination for art lovers, with books, films, and, more recently, immersive experiences dedicated to the Dutch artist. Van Gogh’s dreamy landscapes and eerie self-portraits have drawn massive crowds at art institutions across the globe, and, with newly authenticated pieces cropping up at the Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo and the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut, interest in the world famous artist continues to grow. To survey some of his most significant artworks, ARTnews asked eight curators of van Gogh from institutions around the world—including the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and the National Gallery in London—to discuss their favorite paintings by the artist. Their responses, listed below, offer insight into van Gogh’s iconic style.

Courtesy Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Nienke Bakker

Curator, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Van Gogh painted this sunlit landscape during his stay in the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, where he had voluntarily committed himself because of mental illness. It was a difficult and lonely period in which he clung to his work, hoping that that would help cure him. This is the view from his window, which he painted and draw many times. For me, this is the quintessential image of Provence: the wide landscape, the scorching sun, the sky trembling with heat. The golden wheat becomes an undulating sea in van Gogh’s vivid brushstrokes. The painting’s symbolism is also beautiful. For van Gogh, wheat was a symbol of the eternal cycle of nature. He saw in this reaper the image of death, “in this sense that humanity would be the wheat being reaped. […] But in this death nothing sad, it takes place in broad daylight with a sun that floods everything with a light of fine gold.”

© Kröller-Müller Museum

Renske Cohen Tervaert

Curator, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Country Road in Provence By Night is probably van Gogh’s last painting from the Provence period. He paints it shortly before leaving the asylum at Saint-Rémy. It is not an existing landscape, but instead one composed at his own discretion: a final reminder of Saint-Rémy and a summary of the many impressions he acquired during his stay. He describes the painting beautifully in a letter to Paul Gauguin: “a night sky with a moon without brightness, the slender crescent barely emerging from the opaque projected shadow of the earth—a star with exaggerated brightness, a soft brightness of pink and green in the ultramarine sky where clouds run. Below, a road bordered by tall yellow canes behind which are the blue low Alpilles, an old inn with orange lighted windows and a very tall cypress, very straight, very dark. On the road a yellow carriage harnessed to a white horse, and two late walkers. Very romantic, if you like, but also ‘Provençal’ I think.”

Photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Bequest of Keith McLeod

Katie Hanson

Associate curator of paintings, art of Europe, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In the autumn of 1889, van Gogh painted the ravine near the asylum in the southern French town of Saint-Rémy. He described it as melancholy and wild, a set of words that, for me, resonate deeply with the restricted color palette and the energetic, textured strokes. The following spring, van Gogh sent this painting to Paris, where Gauguin saw it and responded: “In subjects from nature you are the only one who thinks. There is one that I would like to trade with you for one of mine of your choice. The one I am talking about is a mountain landscape. Two travelers, very small, seem to be climbing there in search of the unknown…Here and there, red touches like lights, the whole in a violet tone. It is beautiful and grandiose.” It is a poignant reminder of the recognition he was receiving and a reminder to look closely for those two figures that sort of blend into the landscape. And, as if this wasn’t enough, Ravine has a secret—van Gogh had reused the canvas, painting on top of his Wild Vegetation composition. If you look closely you can see the texture of that painting beneath.

© Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Nicole Myers

Senior curator of European art, Dallas Museum of Art

During his first month at the asylum of Saint-Rémy, van Gogh was confined to painting scenes within its walls. He longingly wrote of the view glimpsed through the iron-barred window of his bedroom: a wheatfield enclosed by a stone wall, beyond which silvery olive trees and small farmhouses dotted the foothills of the Alpilles. The moment he received permission to leave the asylum grounds, he captured this stunning scene of the wheatfield after a violent storm. It shows van Gogh at the height of his expressive powers, where line, color, and form coalesce into something transcendent. Van Gogh believed in the healing power of art and of nature, and this painting has taken on new meaning these days as I glimpse what I can of the outside world from my own bedroom window. It’s a painting of freedom, of renewal, and ultimately of hope as he picked himself up after his own terrible storm, inspiration for us all.

Wikimedia Commons

Christopher Riopelle

Curator of post-1800 paintings, National Gallery, London

My favorite van Gogh painting is probably still the first one I ever saw as a child—Iris in the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, where I grew up. Of the several Irises he painted in the garden of the asylum of Saint-Rémy, as his mental health waxed and waned in spring 1890, it’s the only one to show a single bloom. It has pushed its way up through the hard earth and coarse grass alone, tall and gawky, almost defiant, protecting a few other, even frailer stalks which have yet to bloom. I find it hard not to think of this painting as a declaration of hope, and a kind of surrogate self-portrait as well. It must have been a good day for Vincent, among many bad, when acute observation and technical control of line and color were at their peak.

Courtesy Detroit Institute of Arts/City of Detroit Purchase

Jill Shaw

Curator of European art, 1850–1970, Detroit Institute of Arts

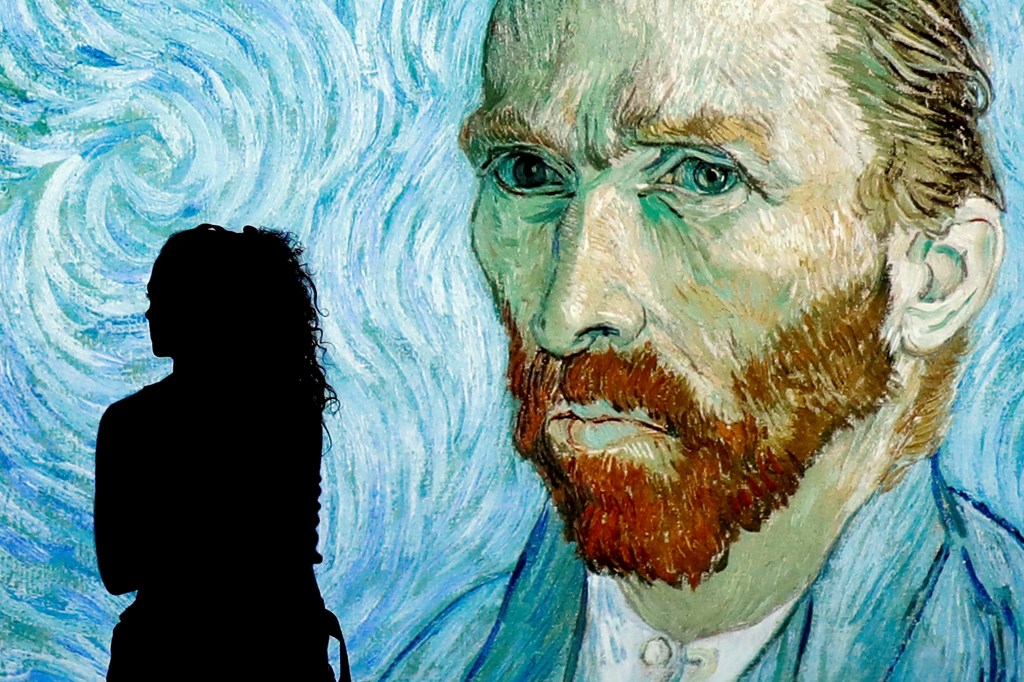

It is an incredible challenge to pick a favorite van Gogh—so many of his early drawings are exquisite, and his talent as a colorist is especially notable later in his career. Among my many favorites is his Self-Portrait (1887, Detroit Institute of Arts). Van Gogh drew and painted himself some 40 times, and this work—which reflects his engagement with avant-garde artists in Paris upon his move there in 1886—is created out of a tight network of painted blue, green, pink, and yellow hash marks that virtually dissolve in front of your eyes as you approach the work. However, the painting is especially important to me because of its provenance: when the Detroit Institute of Arts purchased it in 1922, it was the first painting by the artist to be bought by a public American museum. In 2022, the Detroit Institute of Arts will be celebrating the 100-year anniversary of this landmark event with an exhibition devoted to the artist’s reception in the United States.

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

Susan Stein

Curator of 19th-century European painting, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Met’s Wheat Field with Cypresses unfailingly holds its allure. By the time van Gogh painted this exuberant study from nature, in early summer 1889, he had settled into institutional life and found his footing in the rustic and rugged countryside surrounding the asylum at Saint-Rémy. Familiar enough with the lay of the land to scope out a vantage point that gives full currency to the repertoire of motifs (cypresses, olive trees, wheat fields and mountains) he felt were most characteristic of Provence, van Gogh painted the composition with unhesitating ease and gusto. Each of the subjects and challenges that had engaged his focus—from the “difficult” greens of the towering cypresses to the “devilish yellows” of the sun-scorched fields—are here woven into a harmonic whole with dynamic brushwork that weds the expressive potential of color and line and succeeds to harness the power of both with confident aplomb.

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Audrey Jones Beck.

Gary Tinterow

Director, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The Rocks is a brilliant and idiosyncratic painting. Brilliant because of the extraordinary variety of brushstrokes that van Gogh had adopted from his path-breaking reed pen drawings. Perhaps the vigorous drawing of a similar motif, The Rocks of Montmajour with Pine Trees at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, explains the clarity of this picture. Van Gogh also made a drawing of the completed painting and sent it to Emile Bernard. It is an idiosyncratic picture because landscape theory dictates that the subject should not be placed in the center of the composition. Here, van Gogh is showing us his study of the Dutch masters, for it is precisely there that one finds the rule—made by Italians and enforced by the French—broken. Standing in the heat of the Provencal summer of July 1888, Vincent may have channeled van Goyen’s Landscape with Two Oaks (1641), acquired by the Rijksmuseum in 1870. But what I love most about this painting is the palette: cobalt blues, emerald greens, dusty oranges, in contrast to the melted ice-cream sky. The way Vincent blended wet on wet paint is thrilling. I smile every time I look at it.

[ad_2]

Source link