[ad_1]

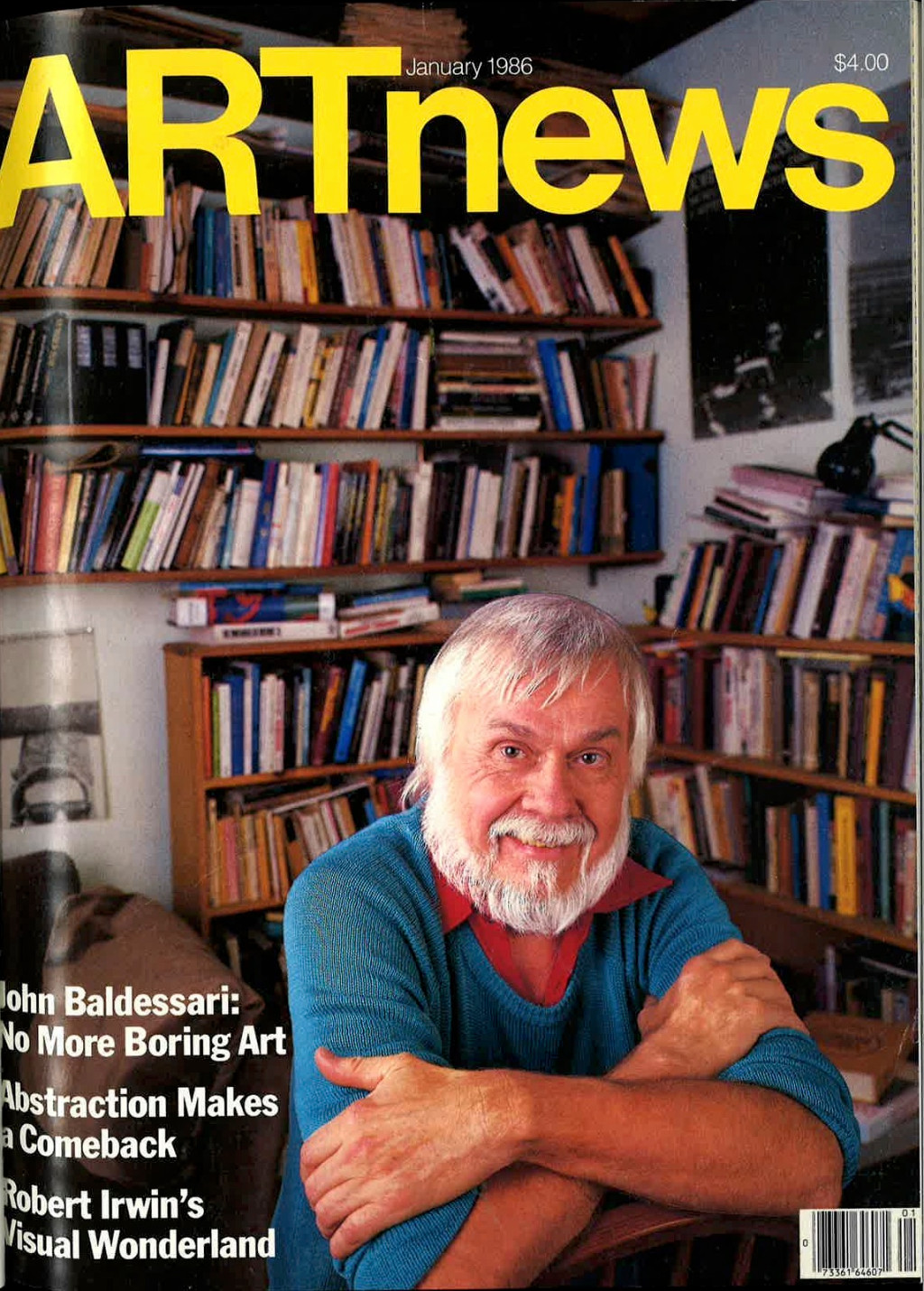

When artist John Baldessari died on Saturday at 88 years old, the art world suffered a major loss. To pay tribute to the famed Conceptual artist, ARTnews is republishing a profile of Baldessari that ran in our January 1986 issue. The article surveys Baldessari’s output, which often took the form of witty photo-based works that privileged ideas over images, and features words from some of his admirers, including fellow Conceptualist Lawrence Weiner, who calls Baldessari “one of the few humanistic and intellectual artists in the United States.” Reprinted with permission from the author, the article follows in full below. —Alex Greenberger

“No More Boring Art”

By Hunter Drohojowska

January 1986

‘I’m constantly playing the game of changing this or that,’ John Baldessari says, ‘asking you to believe the airplane has turned into a seagull and the sub into a mermaid…’

The artist hauled out painting after painting, leaned each against a packing crate and gleefully kicked his foot through every canvas. Portraits of friends, studies of pine trees, landscapes, still lifes, a few abstractions, Pop-style paintings on scraps of billboard—13 years of accumulated work, now in ruins, was taken from the Jewish Museum to a mortuary and cremated. The ashes, in a book-shaped urn, were interred behind a bronze plaque that read: “John Anthony Baldessari, May 1953-March 1966.”

That gesture of destruction, performed in 1970, established Baldessari as one of the first Conceptual artists. He rapidly earned international attention and respect by advocating the supremacy of idea over execution in art.

“I stopped painting because I feared I might be painting for the rest of my life,” Baldessari recently said. “After a certain period of time, one knows how to make beautiful things.

“First, I had the idea of making each painting into a microdot and mailing them to my friends under the postage stamps. But I thought it would be more phoenixlike to rise from the ashes. It seems a little weird now, but at the time it seemed like a perfectly reasonable thing to do. I felt wonderfully free.”

Baldessari, 54, sipped a Scotch during a rare break at the Santa Monica studio he has called home since 1970. The absence of paintings or sculptures in the vast warehouse reflects his “post-studio” esthetic. Floor-to-ceiling shelves sagging with books line the walls of three rooms. Filing cabinets complete the decor. Behind the photography darkroom is a tiny bedroom, where a Sol LeWitt drawing hangs like a crucifix over the bed. Baldessari was preparing for a trip to the Paris Biennale, where several of his pieces were to be shown. “I travel so much, people in New York often think I live there. According to my American Airlines statement, I flew 40,000 miles last year.”

Baldessari was one of the first artists to legitimize the fine-art use of imagery drawn from popular media: television, movies, newspapers and advertising. He shows annually at the Sonnabend Gallery in New York and often in Europe. But in Los Angeles, his hometown, people can still be heard to ask: “John who? Oh yeah. The tall guy with the white hair who goes to all the openings.” His show at the Margo Leavin Gallery in 1984 was, in fact, his first solo show in that city since 1970.

Given the state of things, why does Baldessari stay in Los Angeles? “A sense of permission,” the artist says. “There’s a daffy quality of ‘why not?’ Also, I need to be a little bit angry to work, and L.A. makes me angry. It’s not a pretty city. I get angry at artists for being so dumb, and that makes me work. I’m angry at the chauvinism of L.A.”

[Read the ARTnews obituary for Baldessari.]

Baldessari stands a lanky six foot six, distinguished, even professorial, with his white walrus moustache and beard. His blue eyes, however, are as mischievous as a child’s, and his hands look surprisingly delicate as he turns the pages of a catalogue from his retrospective at a German museum. He points to an illustration of one of his favorite works, Concerning Diachronic/Synchronic Time: Above/On/Under (with Mermaid) (1976). It is composed of six movie stills: floating at the top are an airplane and a bird; in the middle are two shots of a motorboat, entering by the frame on the left and leaving by the one at the right; and resting on the bottom are a one-man submarine and a mermaid.

“I wanted the work to be so layered and rich that you would have trouble synthesizing it,” Baldessari explains. “I wanted all the intellectual things going, and at the same time I am asking you to believe the airplane has turned into a seagull and the sub into a mermaid during the time the motorboat is crossing. I am constantly playing the game of changing this or that, visually or verbally. As soon as I see a word, I spell it backward in my mind. I break it up and put the parts back together to make a new word.”

Baldessari, who once thought of becoming an art critic, clearly has a writer’s sensibility, so his parables work on a literary as well as a visual level. They serve contemporary fairy tales, subtly injecting myth, allegory and metaphor into the avant-garde context. Baldessari began to work with photos and text in the late ’60s. At that time many artists had decided to abandon the production of objects as a reaction against the heroic stance of the Abstract Expressionists and as a rejection of what was seen as the rampant commercialization of the art world. As an alternative, Minimalists embraced pure form and Conceptualists such as Baldessari chose pure content.

In the early days, Baldessari was occasionally criticized for being insufficiently “pure.” But his friend and fellow Conceptualist Lawrence Weiner has described him as “one of the few humanistic and intellectual artists in the United States. John is most pure because he understands that art is based on the relationship between human beings and that we, as Americans, understand our relationship to the world through various media. We think of any unknown situation in terms of something we’ve seen at the movies. This is the basis of our normal mass consciousness and how we see the world. John is dealing with the archetypal consciousness of what media represent, using the material that affects everyday life. High art is useful to society and helps people understand and relate to the world.” Baldessari seems to need to feel that his art has some useful purpose. As Weiner puts it, he is “moral, responsible—a Calvinist artist.”

Courtesy the Estate of John Baldessari and Marian Goodman Gallery

Baldessari pops a slide into a desktop viewer. The screen glows with a composite of black-and-white movie stills, and the artist admits conspiratorially, “I love my titles.” Man with Nails/Car/Reluctant Man (1984) is a streamlined horizontal triptych of a man with a pair of nails dangling from his lips, a car (an elongated dragster called “Goldenrod”) and a man on the edge of a diving board, uneasily pondering a jump. The disjunction in the combination of literal titles and utterly strange and disconnected pictures makes us laugh. As in much of Baldessari’s work, the dry wit has a strong impact, leaving the impression that he makes funny art. Baldessari protests, “I think of humor as going for laughs, and that is not my purpose. I see my work as issuing forth from a view of a world that is slightly askew.” Each of the images has a symbol as well as a literal value, as in a visual poem. “I saw that guy with nails in his mouth as a young soldier ready to crucify someone,” he explains. “I wondered how long that habit—putting nails in your mouth—goes back.”

Baldessari’s composite photographs represent the duality of order and chaos, a fundamental opposition that can be found consistently in his work since 1966. It may be manifested in the dichotomies of heaven and hell, birth and death or love and hate—all fundamental oppositions Baldessari has absorbed from religion. He attended church regularly through his late 20s and once considered abandoning art to accept a scholarship to the Princeton Theological Seminary. He has always been interested in the way the world works.

“Even in freshman philosophy class,” recalls Baldessari, who went to San Diego State College, “I remember asking the teacher, ‘What is order? And if you know what order is, what is disorder?’ He just looked at me, you know, like, this is one of the fundamental philosophical questions coming from this kid. At what point did chaos become order? Or is chaos a different kind of order? Or does it have to be ordered for us to perceive it?

“The larger issue for me is boredom. Geminis are supposed to get bored, and I do hop from subject to subject. It’s this feeling of constant dissatisfaction that keeps me from trying to find order. I can endlessly speculate on something that is not conventionally ordered. Like I’m fascinated by the way we say, ‘This is not a good painting.’ Why not? How inbred are our reasons? In my art, I push that. I constantly qualify things.”

Baldessari ambles over to a big box containing file folders full of movie stills categorized from the obvious (“art”) to the arcane (“looking up/looking down”). When asked how he selects his images, the artist sighs. “It’s a very slow, torturous, arduous, winnowing process that begins with visits to places and sell movie stills. It’s a process akin to going to bookstores. It gives me an idea of what’s on my mind; it’s a way of bringing that intuitive stuff up from below, giving it shape and finding out what it is.”

Baldessari also selects his imagery from television. “The world constructed by the media seems to me a reasonable surrogate for ‘real life,’ whatever that is. I decided that aiming my camera at the TV set was just as reasonable as aiming it out the window,” he says.

Curator and art writer Coosje van Bruggen, who is compiling a book on Baldessari’s work from 1969 to 1984, says, “He uses movie stills as a code people know to get them involved. But his work is all about balance and the immediate possibility of unbalance, enhanced by the composition. Every single piece of John’s work is like an invitation to a dialogue. The things that stay constant are the narrative approach and the use of photography.”

[ad_2]

Source link