[ad_1]

Installation view of the Whitney’s “1985 Biennial Exhibition,” with, left to right: John Duff’s Irregular Column, 1984, and Donald Judd’s Untitled, 1984, and Untitled, 1984.

GEOFFREY CLEMENTS/COURTESY THE WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART

The following is excerpted from the forthcoming book Donald Judd Interviews (David Zwirner Books/Judd Foundation), an anthology of talks and discussions—edited by Flavin Judd and Caitlin Murray—with the storied Minimalist artist spanning four decades of his career. —The Editors of ARTnews

Donald Judd frequently criticized large museum exhibitions in his writing and interviews. In his 1989 essay “Ausstellungsleitungsstreit,” for example, he wrote that very large exhibitions “never provide a true sense of what is being done in contemporary art. Most large collections of contemporary art are also not relevant… The best work of the time is never seen together. The organizers promote work they favor; they regard art as a ‘scene,’ anything that occurs. In New York City examples of this are the annuals of the Whitney Museum of forty years ago, as well as now.”

Judd had two works included in the 1985 Biennial Exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. To promote the biennial, the Whitney created a half-hour-long television documentary, American Art ’85: A View from the Whitney, which aired as part of a weekly series through July and August 1985 titled You Gotta Have Art on Channel 13 (now WNET), a public television station that serves the New York metropolitan area. American Art ’85 was written, produced, and narrated by Russell Connor, a painter and former head of public education at the Whitney. Only a brief statement by Judd was included in the documentary.

Russell Connor: You started off part one of the article [“A Long Discussion Not About Master-Pieces But Why There Are So Few of Them: Part I,” from 1983, republished in Donald Judd Writings] by saying, “The quality of new art has been declining for 15 years… There have been almost no first-rate artists in this time.”

Donald Judd: To start from another angle on that: I think that you have a bad situation now because—this is a little more, perhaps, fundamental than that as an idea—the art in the United States originally was made in a very private way, and not necessarily to sell. And it was not very large, or, if large, it was paintings. At the present time, the art has gotten beyond the making of portable paintings or objects and beyond the cash-and-carry situation, which seems to be the only one that will work. It’s necessary now to do art—or artists want to do art—that is more involved with architecture, is larger, and, in my case, with three-dimensional work, is expensive to make. And to try to do any of this is next to impossible to do, because there’s no institution that will cooperate, and there’s virtually no interest in having it done. So primarily what you have is a simple cash-and-carry situation, and it hasn’t gotten beyond that. It’s kind of like the first folks in the Amazon or something; it’s a rather rudimentary civilization. It’s completely going to pot, because there’s no allowance for the ambition of the artist to do something beyond these small saleable things. Now you have an even worse situation, where the art is even—with all the trouble that it takes even to get it made, it now is threatened with destruction, as in Richard Serra’s case. [Serra’s large public sculpture Titled Arc, installed in Manhattan’s Foley Federal Plaza in 1981, was the source of much controversy before it was removed as a result in 1989.]

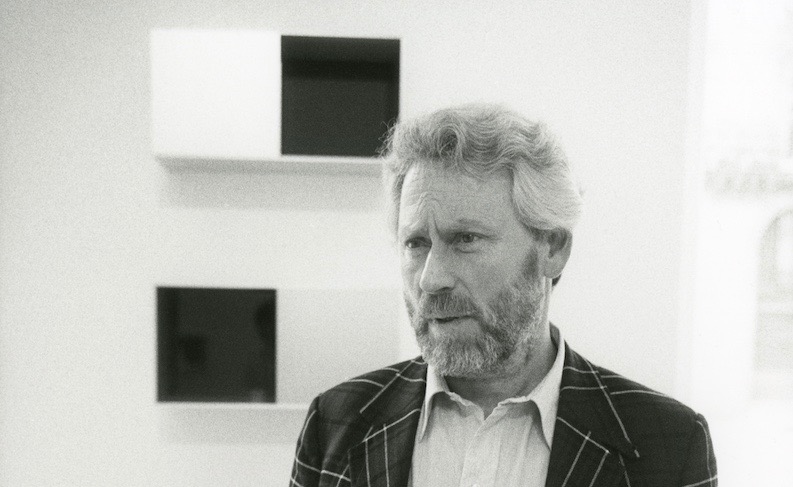

Donald Judd at Galerie Lelong in 1987.

MICHEL NGUYEN/©GALERIE LELONG PARIS

Connor: What relation does this have to the problems of business as a sponsor and art being reduced to a commodity?

Judd: Art’s not a commodity, and everybody should fight that idea. Business as a sponsor could be all right, but they don’t really know very much about art, and they don’t want anything beyond these portable objects and paintings, because it’s too hard for them to deal with, and too complex. Every time you get beyond this point, there’s a great deal of red tape and interference by people who don’t know anything about it, until finally nothing happens.

Connor: But as lamentable as business might be—as patronly and preferable to government bureaucrats or the nouveau riche—

Judd: Well, the nouveau riche are also the business people; they go hand in hand. I don’t think the government should have anything to do with art, as I said in the article. I think it’s an exceedingly dangerous institution. I was always against the idea of the National Endowment grants and so forth. Now they’re proving themselves, as again—with the case of Richard Serra and, I think, Bob Murray and other people—to be a total pain in the neck. What little was achieved is going to be destroyed. As I said in the article, the government can buy something if they want it, just like anyone else—buy what they like. If they want statues of somebody, they can buy statues of somebody. It’s harmless and you can’t do anything about it, so—

Connor: How does that situation as you describe it explain what we see on the walls of the biennial?

Judd: As I said in the beginning of the article, ultimately, it’s the responsibility of the artists to make good art, and there’s no other way around that—that’s the fundamental situation. I think the government involvement in the past 15 years, and more and more in museums, makes a greater institutional situation, and I think that institutional situation is destructive, and I think for the younger people they’re probably more vulnerable to that. Everybody gets in the habit of filling out the forms for grants and competing. I was objecting the other day about competing for commissions; I don’t think artists are supposed to have to compete against one another, it’s not that kind of activity. So you’re sucked in—in order to work, you’re sucked into this bureaucratic situation. I think that kind of spreads out throughout the whole situation, and, as I said, especially with younger people. When I began, there was hardly any art situation at all, so it’s hard to be corrupted by something that doesn’t exist.

Connor: Could you touch on that?

Judd: The commerce gets more tied into that; I think the commercial dealers and the institutions sort of come together much more than they used to. But these social reasons don’t explain all these things—never. They’re a factor, but they’re not the ultimate explanation. You also have to have people—and this goes on to the whole article, I mean—you have to have people who will say that things are good or bad. You don’t have decent criticism, you don’t have support for the art that’s better, and it becomes a very lax situation.

Connor: I want to get into that criticism: “For a century there have usually been two versions of each art, one real, but poor and underground, and one fake, although rich and conspicuous. The latter ingests the former as needed” [from the same article cited above]. Can you expand on that in relation to today’s situation?

Judd: The art that’s in the history books is ordinarily the art that has been done pretty much by the artists on their own without any great financial support—and if you go around the cities and look at what actually got done, it’s art or architecture that isn’t very good that received the bulk of the money and is still there. This is happening now, too, as it’s always happened. You see big expensive statues—I saw some elaborate thing in Bordeaux by someone I had never heard of, done around 1850 or 1860. It probably cost half the taxes of Bordeaux for a year to put the thing together. It’s not by Rodin—who was later—or anybody who, you know, you would think is important now. All the architecture that so much money is going into now is not serious architecture.

Connor: A hot topic going around the Whitney these days.

Judd: It’s going to be a bad building. I’ll say that in public. [In 1985, the Whitney Museum developed plans for a 10-story addition by architect Michael Graves; poorly received, the proposal was dropped in 1989.]

Connor: [Laughs]

Judd: I jumped on Michael Graves in the article.

Connor: Yes, I noticed. Art and democracy—the idea that art should be democratic—you say, “Politics alone should be democratic. Art is intrinsically a matter of quality.”

Judd: Yeah.

Connor: What about quality?

Donald Judd Interviews on a table at the Judd Foundation.

ALEX CASTO/COURTESY DAVID ZWIRNER

Judd: Quality is not undemocratic. Quality is simply quality. It’s not a form of elitism or anything; it’s something well done. You don’t say that a good astronomer—since I was just at an observatory7—is undemocratic; he’s doing a good job. Art is a cheap target for the government because it doesn’t cost much; it’s really cheap as a way to wave democracy, and if they were really serious about it, they would be democratic in areas where it really counts. But they can claim, as they do, to distribute the awards to artists all the way across the United States, no matter what the quality is, just so someplace will get one. These things are against the integrity of art, and any kind of fooling around with the politics of art and the politics in art is very bad for it. Quality in art has nothing to do with democracy. I think it’s just a cheap shot at art, and ultimately, it’s a cover-up for real politics by citizens, which the United States government does not really want to happen. The issue of democracy and art is sort of a smoke screen to keep the folks from really being serious about the government intervening.

Connor: In the biennial—as around in the galleries—there’s a lot of work which borrows conspicuously from the art of the past, as is going on in architecture too. You say, “In art and architecture it’s impossible to use forms from the past. They become symbols, and not profound ones either”—

Judd: There’s no way that you can really understand the art that was done in the past. It’s too different. You can’t even understand another person’s work in a way whereby you could do it and add to it—living at the present. It’s a total illusion that you could understand anything about the art of the past and make something that looks like it in the present and have it be good art, because the gap in information and way of living and everything is too great. I think this gap is so profound; evidently, other people don’t think so, but—

Connor: What about in quotations, where bits and pieces are used, where they’re obviously not trying to re-create—

Judd: It’s ridiculous. It’s a total failure of invention in the present and them doing something new. The quotations are also so incredibly trite most of the time; it’s kid’s stuff.

[ad_2]

Source link