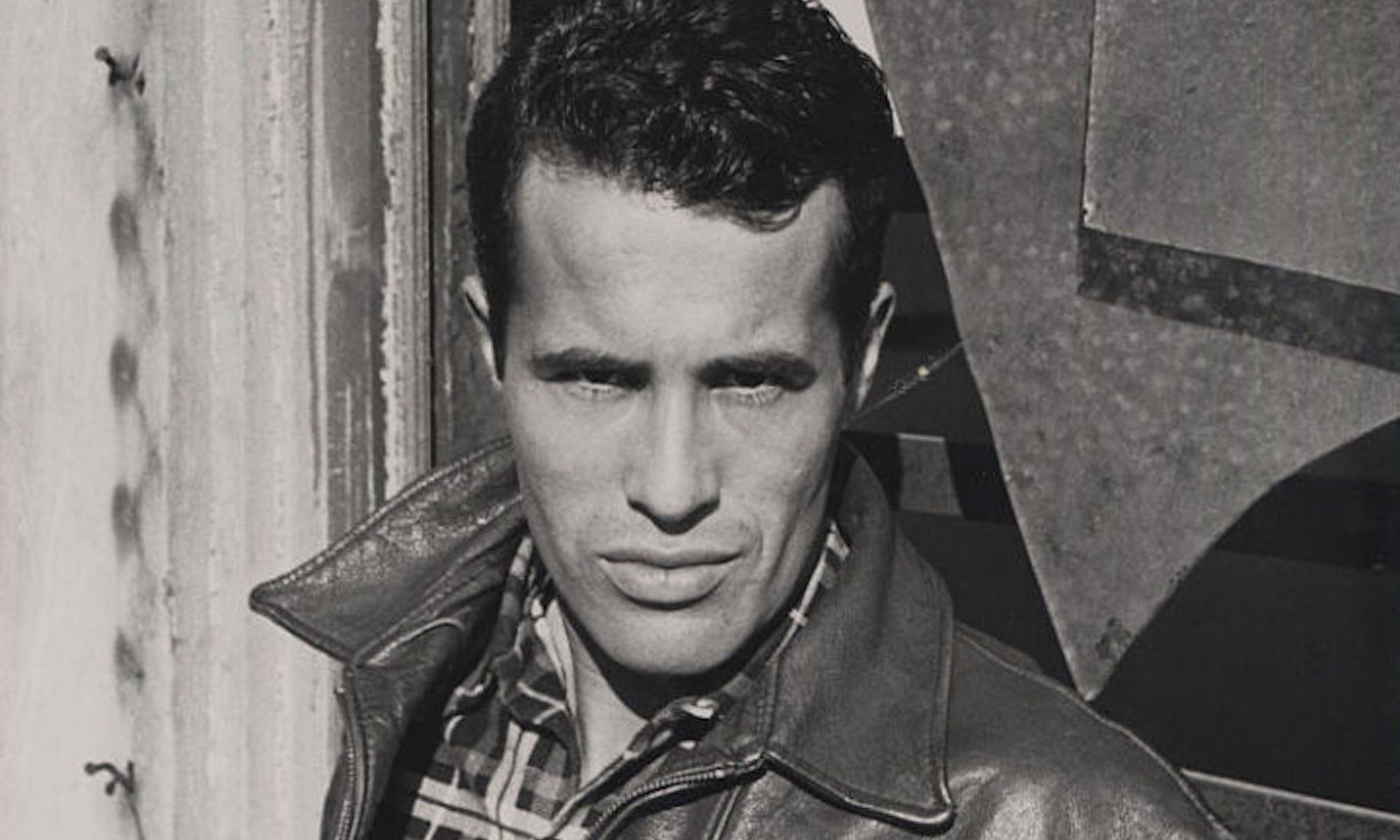

Kenneth Anger in 1954. Photo: Chester Kessler

Kenneth Anger, a monumental figure in American avant-garde cinema and moving image art, died on 11 May at an assisted-living facility in Yucca Valley, California. He was 96 years old. His death was confirmed by Monika Sprüth and Philomene Magers, the gallerists who have represented Anger since 2009.

Anger was best known for his transgressive, boundary-pushing cinematic works, including such films as Fireworks (1947) and Scorpio Rising (1963), which went against the formal and social constraints of their day and, in the process, helped map new terrain for American underground film and ultimately pop culture at large.

Kenneth Anger, Fireworks, 1947 © The Estate of Kenneth Anger, 1947. Courtesy Sprüth Magers, 2023

Anger was born Kenneth Wilbur Anglemyer in 1927 in Santa Monica, California, to a middle-class Presbyterian family. Although he would later claim, in a characteristic act of self-mythologisation, that he had acted in a 1935 version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, his first confirmed experience with filmmaking came in 1937—at age ten—when he made his very first short film, Ferdinand the Bull, on a roll of 16mm film left over from a family vacation. He continued making films throughout adolescence, often riffing on classical mythology and science fiction serials. He quickly developed a knack for formal and conceptual experimentation. “I call them cine-poems,” Anger said of his work in an interview with Dazed in 2011. “They are not narrative films but rather, stories told in pictures.”

These experiments eventually crystallised in his 1947 film Fireworks, a jittery, jump-cut concoction of haughty Greek-tinged drama and surrealist psychosexual pulp that was also one of the earliest examples of explicitly queer experimental cinema. The film, which features an orgiastic centrepiece of masochistic masculine violence, eventually became the subject of an obscenity trial that, after it went all the way to Los Angeles County Supreme Court in 1959, helped loosen restrictions on so-called “obscene” content in the arts.

Kenneth Anger, Lucifer (Leslie Huggins), 1970-81 © The Estate of Kenneth Anger, 1981. Courtesy Sprüth Magers, 2023

In the years after Fireworks, Anger continued to push at the aesthetic and political bounds of tact and good taste. He embarked on a number of creative projects, including a bevy of short films as well as his infamous 1959 novel Hollywood Babylon, which detailed a host of sordid half-truths about the lives and deaths of various Tinseltown celebrities.

In 1963, he released perhaps his most famous film, Scorpio Rising, a lysergic mix of leather, religion and authoritarian violence whose intentionally blasphemous content—including clips of leather-clad bikers spliced with both Christian and Nazi iconography—tracked with Anger’s interest in the occult teachings of Aleister Crowley and the Satanist Anton LaVey. Over the next decade, Anger would extend his pursuit of these occultist visions, culminating in 1972’s Lucifer Rising. After its release, Anger did not produce another film for nearly 30 years.

Kenneth Anger, Scarlet Woman (Marjorie Cameron) from Inauguration of the

Pleasure Dome, 1954-66 © The Estate of Kenneth Anger. Courtesy Sprüth Magers, 2023

During this hiatus, Anger’s unique brand of pop-flecked transgression blossomed into something unlikely: a genuine artistic mainstay. Hollywood auteurs such as David Lynch and Martin Scorsese have cited Anger as an influence, and his propulsive soundtracks and editing have even been credited with foreshadowing (and possibly shaping) music video aesthetics. While Anger may have stayed firmly on the side of transgression, his artistic influence has spread to many corners of the visual mainstream—perhaps a fitting legacy for a persistent pusher of boundaries.

“Kenneth was a trailblazer,” Sprüth and Magers said in a statement. “His cinematic genius and influence will live on and continue to transform all those who encounter his films, words and vision.”