[ad_1]

“Art of the City” is a weekly column by Andrew Russeth that runs every Tuesday.

LAST THURSDAY, AS NIGHT FELL, the artist Keith Sonnier—one of the most venturesome sculptors of the past half-century, and also one of the most underrated—was lounging in a room high up in the sumptuous new Equinox Hotel in Hudson Yards. The nearby Kasmin gallery had put him up there—Sonnier lives in Bridgehampton, out on the South Fork of Long Island—so that he could be present for his opening. Though he has been ill recently, the 78-year-old was in an ebullient mood, uncorking stories about his art and his life.

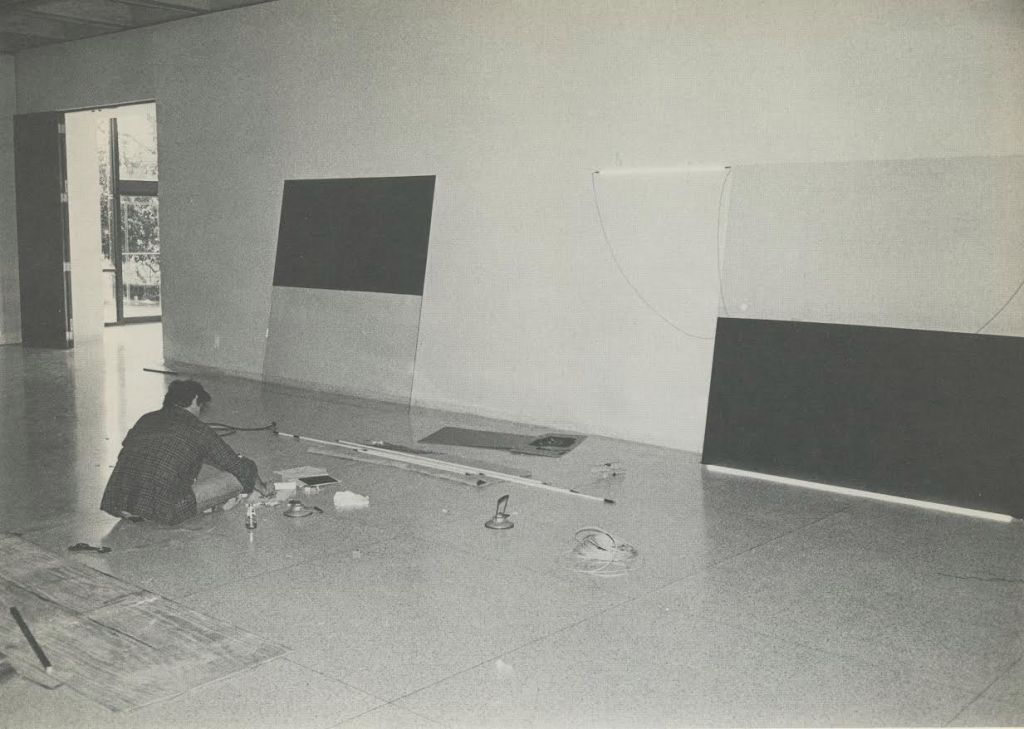

The light-and-glass sculptures on view at Kasmin (through January 11) come from Sonnier’s “Ba-O-Ba” series, which he started early in his career, making pioneering use of neon tubing. They are both new and old: freshly fabricated from drawings that date back more than four decades.

“I had always wanted to do the source of where ‘Ba-O-Ba’ came from,” he said, with vestiges of the twang he acquired growing up in rural Louisiana. Sporting a boxy white moustache and a tan sweater over a collared shirt, Sonnier looked part private investigator, part history professor. Fittingly, he was thinking about his past.

As the story goes, Sonnier came up with the name of the series in 1969, when he was vacationing in a remote part of Haiti with Gordon Matta-Clark, another artist then enlivening the downtown Manhattan art scene. “We took the bus over the mountain to Jacmel, this little mountain town,” he said. Near their hotel was a bay with a “little fishing skiff in wood with a white sail.” Its fisherman told the artist he had named it “Ba-O-Ba”—a Haitian Creole phrase loosely meaning “bathing in moonlight”—since he did his fishing under the moon.

In his own work, Sonnier has said, “the viewer is inside the light. You are in the moonlight so to speak, bathed in light … very biblical.”

The “Ba-O-Ba” works at Kasmin present Sonnier at his most poised and balanced, with lines of red, blue, and yellow neon sitting alongside squares of clear and opaque black glass. He titled the show “The Louisiana Suite” because the name “rings of a kind of musical suite in classical music,” he said.

© 2019 Keith Sonnier / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photograph © Caterina Verde

As he spoke about the show, Sonnier kept returning to Louisiana and growing up in a bilingual Cajun family. Seeing the finished pieces, he said, cryptically, “I thought that they adhered to other times in my life.” He mentioned his father, who owned a hardware store and read voraciously. “I’d look at the floor and there was everything from trash to classical literature,” he said. His mother owned a flower shop, and his grandmother was a spiritual healer—her kiss brought relief.

There was also a teacher with hair “dyed as black as sin” who once announced, “I’m so depressed today. We’re singing every class!” and then proceeded to let it rip on her grand piano. And there was an aunt who ran a casino in the Gulf of Mexico. Sonnier loved to visit her. “You would hear as you walked in the mud with the rain the rick-rack of the paddlewheel going,” Sonnier said, “and it was just amazing.”

There wasn’t much to keep Sonnier occupied in those days, so he looked to make friends. “I sought out unusual people,” he said. “It was part of my nature. I think when you grow up in the middle of nowhere and you do nothing all day but sit up in a chicken tree”—a Chinese tallow—“and watch birds, you don’t have much else to do.” His outgoing nature served him well in New York, where he became close with sui generis personalities like Matta Clark and Lynda Benglis.

It was almost time to leave for his opening, but Sonnier delivered one parting point. “I think that things about my life and childhood got put together finally in a variety of ways,” he said. “And it took the show to really get the whole thing together and on the road.”

Andrew Russeth/ARTnews

THE BODY POLITIC

If there were an award for the gallery that manages to alight in the most idiosyncratic locations, Ramiken would win it. It spent the past year operating out of an Upper East Side penthouse. A while before that, it occupied a cavernous cement-walled basement beneath a Downtown bank. Now the gallery has taken over the 17,000-square-foot fifth floor of an industrial building in Bushwick, Brooklyn, for an exhibition of work by the artist Andra Ursuta titled “Nobodies.”

Stunning views of Manhattan compete with—and lose to—a group of extraordinary cast-glass sculptures. They are self-portraits, but only in the most expansive sense of that term. Ursuta’s body parts are not always visible, and they are augmented by molds of BDSM gear (masks, boots), sci-fi creatures, and large water bottles. In a spectral green piece, the back of her head is stretched out like the creature in Alien. Meanwhile, the swirling-yellow-and-white Predators ‘R Us is headless, the feet of its classically nude body in slippers that resemble the monsters in Predator.

These uncanny hybrid beings slide in and out of legibility—the human giving way to objects and vice-versa. Both unsettling and alluring, they are mutant amalgams, like us all.

Courtesy Welancora

A WARNING

Helen Evans Ramsaran’s current show at Welancora gallery in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn is a tender, elegiac ode to an environment under siege. Hanging in front of an aquamarine-colored wall are a series of intricate, carved clay sculptures. Some resemble ornamental bowls, while others are wild, spindly abstractions. They are smooth, nuanced, and all white, like pieces of bleached coral reef. They cast bewitching shadows onto the sea behind him.

The title of the exhibition is “12 Years,” the amount of time that the United Nations estimated in 2018 was left to avert catastrophic global warming. This morning it released a report with findings that it described as “bleak”: more cuts are needed—more quick, braving thinking, which one hopes art can help engender. Elsewhere in the show, bronze constructions from the early 1990s radiate some of the freewheeling energy of early David Smith and Richard Hunt, evincing no shortage of ingenuity.

[ad_2]

Source link