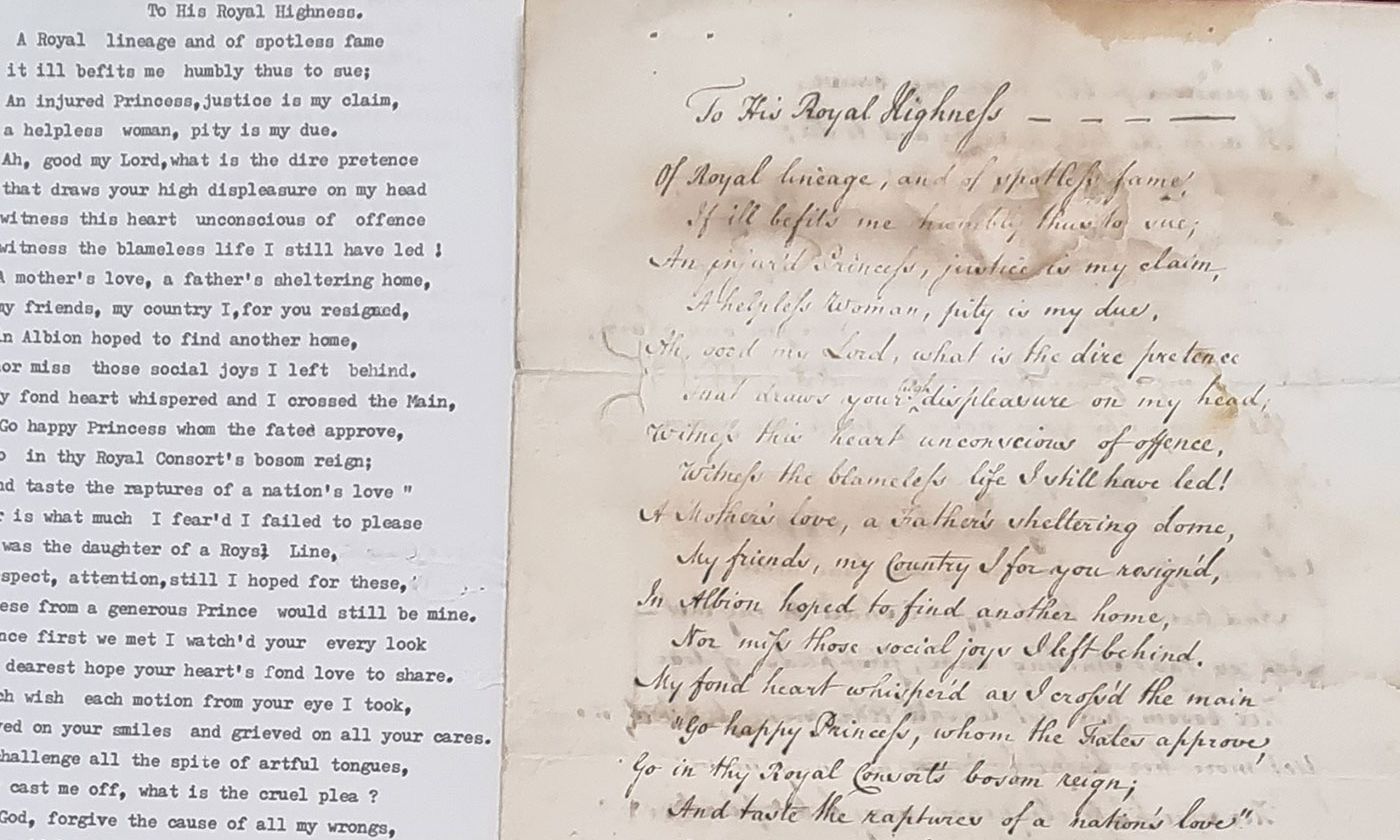

"A fascinating mystery”: the manuscript and typed transcript of "To His Royal Highness", part of a recent bequest to Cambridge University Library of materials relating to the troubled marriage of George IV and Caroline of Brunswick Cambridge University Library

A wail of outrage from a spurned Queen who found the doors barred to her husband's coronation 200 years ago has resurfaced in an archive, just in time for the weekend ceremonies to enthrone Charles III.

It may rain on King Charles’s parade, as it did on his mother’s, or a horse could cast a shoe, a guardsman might faint or a trumpeter hit a wrong note—but whatever minor disasters arise, at least he will not have to deal with a distraught wife hammering on the locked door of Westminster Abbey, pleading in vain for admission, as Caroline of Brunswick did in 1821 to the coronation of her estranged husband George IV.

The manuscript poem, titled "To His Royal Highness", begins:

Of Royal lineage, and of spotless fame

It ill befits me humbly thus to sue;

An injured Princess, justice is my claim,

A helpless woman, pity is my due.

The verse has resurfaced in an archive recently acquired by Cambridge University Library, and although not in Caroline’s hand writing, the 41-line poem is believed to be a contemporary copy, in a file of documents relating to the marriage of Caroline and George IV which was calamitous even by the standards of the British monarchy.

The pair, who were cousins, were married in 1795 despite apparently loathing one another on sight: George, then Prince of Wales, got so drunk on the wedding night that he spent it sprawled on the bedroom floor with his head in the fireplace. As the vicious contemporary cartoonists gleefully pointed out, George also had a wife, the virtuous long-suffering and Roman Catholic Mrs Fitzherbert, but since he had married without royal approval it was not officially recognised. Caroline and George did manage to produce one child, Charlotte, the only legitimate heir among the raft of illegitimate offspring of the many children of George III. Charlotte was extremely popular and married happily, and her death in childbirth in 1817 was regarded as a national disaster.

"A helpless woman, pity is my due": a detail from a 1932 reproduction of Thomas Lawrence's 1804 portrait (National Portrait Gallery, London) of Caroline, estranged wife of the then Prince of Wales—the future King George IV The Print Collector / Alamy Stock Photo

By then Caroline and George had long since separated. The poem may date from “the delicate investigation” of 1806, when George, desperate to find evidence to divorce her or even annul the marriage, set up a tribunal to find evidence of her treasonous adultery. Despite attempts to bribe her servants and friends Caroline was acquitted, and many who loathed George’s lifestyle and spectacular extravagance as Prince Regent (a title he was granted in 1811) declared themselves her supporters—although even her most devoted admirers would hardly have claimed her as “of spotless fame”.

In 1820 George III finally died after years of bouts of insanity. His son finally became King George IV, and staged an extravagant coronation ceremony in July 1821, costing £283,000, more than £21 million in contemporary cost, the most expensive ever. Caroline, still his legal wife, turned up at the abbey but was refused admission. She died only a few weeks later, George in 1830—succeeded by his brother William IV who spared every possible expense at his own £30,000 coronation.

The poem and related papers including dozens of handwritten letters and contemporary copies of letters from the early 1800s—exchanged between Princess Caroline, King George III, and Caroline’s loyal circle of friends and supporters—are part of the Massy-Beresford collection which has been donated by the late Michael Massy-Beresford.

John Wells, Senior Archivist at Cambridge University Library, describes the authorship of the poem as “a fascinating mystery”.

“These letters transport us to a febrile period of royal history. The outline of the story is well enough known to historians, but these personal letters —sent directly to and from the princess and other leading participants— reveal more about the calculations and sensitivities of those most intimately involved. They give scholars insights that can’t be gleaned from the official public record.”