Trending

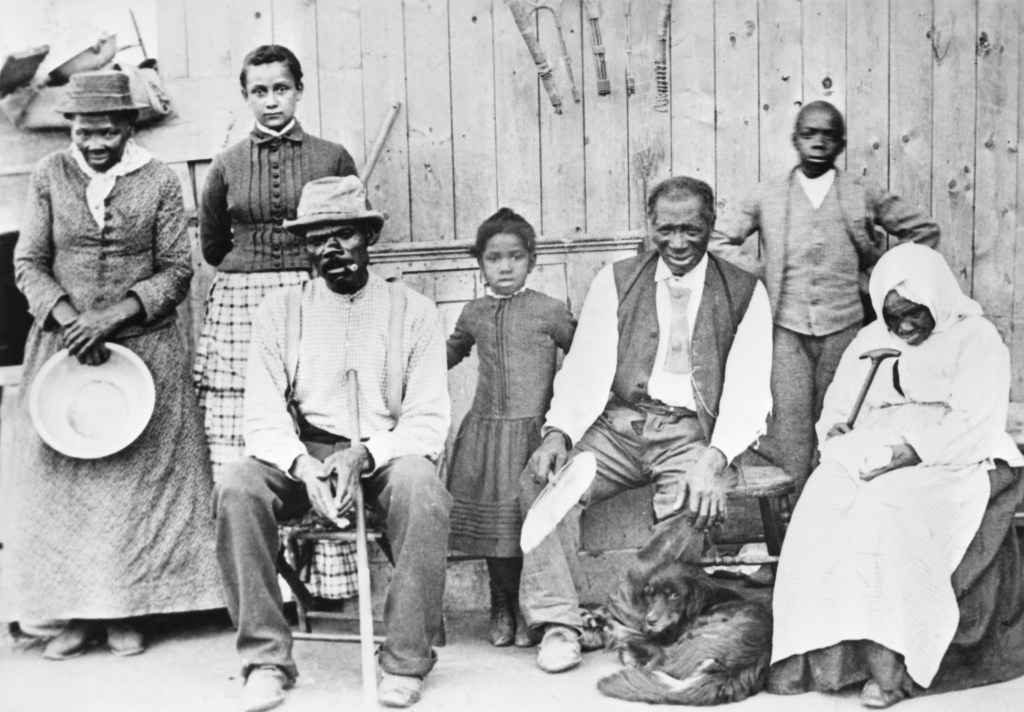

Source: Bettmann / Getty

Juneteenth and I have this memory about an exhibit I once viewed about slavery at the New York City Historical Society. New York once held the distinction of having the most slaves in the North. It was second only to South Carolina. And long after the transport of enslaved Africans was outlawed—it was punishable by death–New York Harbor smoothed the passage of slave ships until at least 1858.

But I remember less about what was said about the horrors of the New York, than I do about the imagery. All the terrible imagery you can conjure: it was there. Beaten Black bodies. Chained Black bodies. Broken Black bodies. All that evidence of the seemingly limitless depth of white American depravity: what Toni Morrison once called unspeakable things, unspoken.

But the images and documents from that exhibit, they came to speak. Sort of.

Their words were constrained, contained. Noosed. They were words that told half-truths that in critical ways, made them whole lies. By their telling, one could easily surmise that the whole truth was that Black people were subjected to the most demonic of institutions and suffered mostly silently until that Oh Happy Day when the “Great Emancipator,” President Lincoln, and other good white people, freed them.

There’s no debate to be had about America’s original sin. It was more brutal, more barbaric, more savage than those of us born seven or eight generations on can likely ever imagine. But to tell that part of the story and only that story is to write a hero’s journey without including a hero. And in this case, the hero was us. Our ancestors.

Like the Emancipation Proclamation Juneteenth is part of the story of Black brilliance and bravery, a point made powerfully clear in the work undertaken by renowned political scientist, Dr. Errol Henderson, most notably in one of his more recent works, The Revolution Will Not Be Theorized.

Henderson, building on DuBois’s work, in particular Black Reconstruction, as well as that of Alain Locke, makes perhaps the argument we most need to know: We were our own liberators.

Source: Photo 12 / Getty

That’s literal, not metaphorical. Specifically discussing the Civil War, Dr. Henderson corrects the oft-repeated narrative that Lincoln and the Union forces initially fought the Civil War to end slavery. Not true. Lincoln cared little about the plight of the enslaved. They could be free or not free, it made no difference to him. The initial goal of the war was to assert and maintain political, economic and social dominance over the entire geography of the country.

Five months before issuing the EmancipationProclamation on January 1, 1963, Lincoln said:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.~ President Abraham Lincoln, August, 1862, Letter to Horace Greeley, Editor of the New York Tribune

Because Black people.

Black people who were subjected to the harshest and most life-threatening circumstances, used their own strategies and creativity, from Fredrick Douglas to the most brutally treated slave whose name we don’t know, saw an opportunity for freedom and took it. That’s how things changed.

What started out as a white man’s conflict became a Black People’s revolution, the one rarely enough referenced in American history courses or scholarships: the one that on this land, by the most harmed of people, a successful revolution was carried out.

And revolution as opposed to rebellion, which is often what Black resistance is reduced to.

Henderson makes a clear distinction: a rebellion is something that a person or a group undertakes to get back to the way things were. We rebel against new laws, higher taxes, for example.

Revolution is about never going back to the way things were. It’s about sea change. It’s about ensuring that the world we once knew, we shall know no more. And everyone wanted in.

Black preachers were key. They were among the Black people who were allowed to travel, ostensibly to spread the word. And they did. But they so setting aside the word of a Lesser God who twice compelled slaves to obey their masters (Ephesians 6:5; Colossians 3:22). Rather they took the opportunity to spread the word of a Higher God who said, Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. (Corinthians 3:17).

Black artisans wrote pass cards to help facilitate movement among the enslaved. They crafted weapons and ammunition.

And before the war was over, some 180,000 Black people joined the Union Army. Another 19,000 joined the Union Navy. In what DuBois called a General Strike, the planters stopped planting and crops in the South failed and soldiers, children and wives began to starve. The white women of the South called upon their husbands and brothers to end the war. And one Black woman, formerly of the South, became the only woman to lead a successful military action during the war, freeing 700 enslaved people: Harriet Tubman.

Ten months after signing the Emancipation Proclamation, President Lincoln would travel to the site of the war’s bloodiest battleground in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. His address was less than 200 words:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

In fact the opposite would end up being true.

The words were indeed long remembered. The soldiers much less so. And yet because of the Black soldiers, the Confederate States of America was defeated as was the system of chattel slavery. Even Lincoln, with his laissez-faire attitude about Black freedom would say that the war could not have been won without the strategic military wisdom and courage of Black people, so many of whom had escaped both slavery and the slave patrols.

And on June 19th,1865, when Union troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, to enforce the emancipation of all enslaved people. And Black troops were there with him, they were among those who posted signs and perhaps spoke the words aloud to those held in enslavement:

You’re free. You’re free.

SEE MORE:

10 Things To Watch In Celebration Of Juneteenth

Amid Juneteenth, The Legacy Of Slavery Is Still Enshrined In The Legal System

The post Juneteenth: The Civil War Was A Black Revolution appeared first on NewsOne.

Juneteenth: The Civil War Was A Black Revolution was originally published on newsone.com

Rest In Power: Notable Black Folks Who We’ve Lost In 2024

Boo’d Up With A BUMP: Ella Mai Reportedly Expecting 1st Child With NBA Champ Jayson Tatum

Tim Scott ‘Will Become A Father’ In August, Trey Gowdy Says

R&B Vocalist Angela Bofill Reportedly Passes Away at 70

Fake Designer Wear Connoisseur, Bishop Lamor Whitehead, Sentenced To 9 Years In Prison, X Says His Mentor Mayor Eric Adams Is Next

3 Signs He Could Be Your Future Husband

Brittney Griner And Her Wife Cherelle Reveal Their Maternity Shoot And We Are In Love

Splitsville? Strange Nicki Minaj Posts Have Social Media Buzzing

We care about your data. See our privay policy.

An Urban One Brand

Copyright © 2024 Interactive One, LLC. All Rights Reserved.