[ad_1]

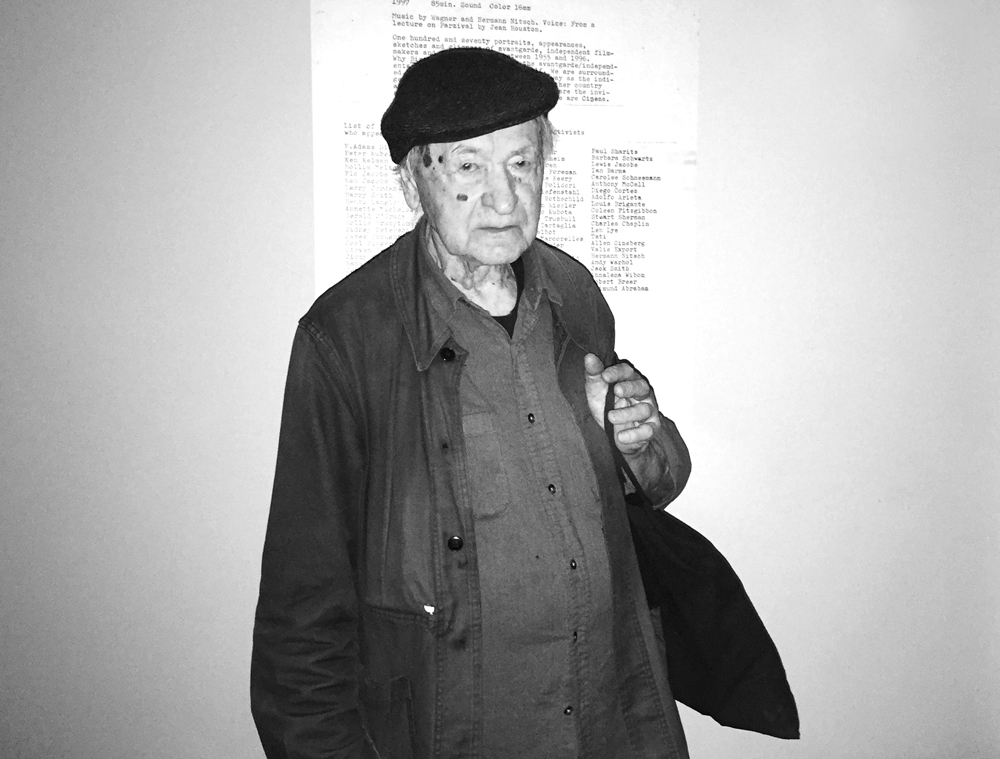

Jonas Mekas.

©KATHERINE MCMAHON

Jonas Mekas, who is widely considered one of the most important figures in the history of experimental film, has died at 96, according to the Anthology Film Archives, a theater in New York devoted to art cinema that was founded by Mekas in 1970. A cause of death was not immediately provided.

“Jonas passed away quietly and peacefully early this morning,” Anthology Film Archives wrote on Instagram. “He was at home with family. He will be greatly missed but his light shines on.”

Though he is frequently credited with helping create a form of cinema that radically broke with filmmaking norms, Mekas resisted the term “experimental.” “No one was experimenting,” he told the Guardian in 2012. “Not Maya [Deren], not Stan Brakhage, and certainly not me. We were making different kinds of films because we were driven to, but we did not think we were experimenting. Leave that to the scientists.”

Mekas preferred the terms “underground,” “noncommercial,” and “poetic” to describe the kinds of films he made, which collapse the division between art and life, and are decidedly uninterested in conventions like plot, character development, and dramatic tension. Without Mekas’s work as a filmmaker and critic, it is hard to imagine what experimental filmmaking might look like today.

During the 1950s and ’60s, Mekas helped crystallize the experimental filmmaking scene in New York. Working with his brother, Adolfas, he founded the magazine Film Cuture in 1954, partly as a response to foreign film publications, like Cahiers du Cinéma. And, starting in 1958, he began writing as a critic, penning a legendary column called “Movie Journal” for the Village Voice. Through his writings, Mekas was able to advocate early on for works that aggressively challenged the techniques being engineered for the era’s narrative cinema. “We need less perfect but more free films,” Mekas wrote in a 1959 “Movie Journal” column reproduced in the 2016 anthology Movie Journal: The Rise of a New American Cinema, 1959-1971, which is one of many books of Mekas’s writings currently in print.

That advocacy extended to Mekas’s efforts to screen experimental films he deemed important. In 1964, for example, Mekas was arrested on obscenity charges for showing Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures and Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour—two works that include explicitly homosexual material. Both films have since been canonized as landmark examples of countercultural filmmaking.

Mekas has often been cited as one of the most well-connected artistic figures in New York during the postwar era. (And without his friendships, some of the era’s most important films—including Andy Warhol’s Empire, which Mekas helped shoot—might not have come to fruition.) His circle included artists, of course—among them Warhol and Salvador Dalí—but it also extended to other luminaries of the New York scene. Jackie Kennedy, the First Lady during the early 1960s, was among those who counted Mekas among her friends, as did the members of the band the Velvet Underground.

At the same time, Mekas was working on his own films. In 1964, Mekas produced his most known work, The Brig, a film version of an Off-Broadway play of the same name by Kenneth H. Brown. Over the course of an hour, the film tells the story of U.S. Marines brutalizing a group of detainees in a Japanese prison in 1957. Though the film’s set is spare, with just a squarish cage structure and some uncomfortable-looking beds, Mekas makes it feel like a documentary—the camera shakes when it circles around the prisoners as their beds are ransacked and they are rounded up like cattle. The footage comes to seem less like art than like life itself.

The Brig was regarded as something new and bold. In its review, Cahiers du Cinéma noted, “When leaving this film, one promises never to see it again. For it seems impossible to watch such a spectacle twice.” When it screened at the 1964 Venice Film Festival, it was awarded the Grand Prix for documentary filmmaking.

Much of Mekas’s photography and filmmaking in the intervening decades blurred this boundary between art and life. He often described his work as “personal” (as opposed to “public” Hollywood filmmaking) for the way it dealt often with people and places that he knew well. His 1969 film WALDEN comprises a three-hour montage of home movies, the subjects of which include wind blowing through leafless branches, the film historian P. Adams Sitney holding up his hand for the camera, and a woman playing with a daisy. The film’s form is something to behold, with a jagged soundtrack and equally jagged editing that jumps between color and black-and-white and back again.

In 1970, working with Jerome Hill, Sitney, Peter Kubelka, and Stan Brakhage, Mekas opened the Anthology Film Archives. Founded as a center for experimental film, Anthology began as a showcase for a series called “Essential Cinema,” which featured regular screenings of masterpieces dating as far back as the early years of cinema. With its stripped-down interiors and its lack of a concession stand, Anthology established itself early on as a place for serious film viewing. Today, decades later, Anthology continues its “Essential Cinema” series and remains a hub for the New York art and film worlds.

Throughout his life, Mekas was hailed for his resiliency, working prolifically until the end. Many have pointed to his childhood in Europe as a marker of his character. Born in Semeniškiai, Lithuania, in 1922, Mekas developed a mystery illness that left him frail and sickly as a child. In response, Mekas devoted himself to reading. When the Russians invaded Lithuania in 1940 during World War II, Mekas photographed the tanks he watched arrive, only to have his camera taken away from him by a Russian soldier.

The following year, after the Germans arrived in Lithuania, Mekas joined the Resistance, only to run away with his brother, Adolfas. The two were arrested and thrown in a Nazi labor camp in Hamburg, Germany. Once the war ended, they wound up in a displaced persons camp.

Finally, in 1949, Mekas emigrated to New York—a decision he frequently discussed in ecstatic terms. Once he arrived in the city, like many other soon-to-be filmmakers of the era, he began voraciously consuming movies that he hadn’t had access to during the war. “I was 27 and I had to make up for all the lost time in the displaced persons’ camp, so I started absorbing everything,” he told the Guardian. “I went to the cinema every day. I was so hungry for culture, for stimulation. It was all about grabbing the time, doing something after so many years of doing nothing. And, when my eyes were opened to what others were doing, it was only a small step to start filming.”‘

Two weeks after arriving in New York, he attended a screening of Maya Deren films at Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16 film society. That fateful event inspired him to go out and buy a Bolex 16mm camera. For the following seven decades, he continued making films.

In the past couple decades, Mekas’s work began appearing in art-world settings. His work was the subject of a retrospective at the Serpentine Galleries in London in 2012 and later, in 2017, at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea in Seoul. James Fuentes Gallery represented him in New York, where his solo show “Notes from Downtown” was on view into the fall of last year. Fuentes, who called Mekas a “mentor,” told ARTnews, “He was just one of those people that had an incredible life force. In 200 years time, when people see Jonas Mekas’s films, they will get an incredible insight into history spanning from post-World War Germany and Lithuania until the day he died. He had so much purpose in his work.”

Mekas featured in Documenta in Kassel, Germany, in 2002 and 2017, as well as the Venice Biennale in 2003 and 2005. In the latter Biennale, Mekas represented Lithuania with a selection of his films from throughout the years. The jury that year awarded Mekas’s pavilion a special mention.

The 2017 edition of Documenta featured examples of Mekas’s diaristic filmmaking. On view was Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972), which focuses loosely on Mekas’s return to his hometown Semeniškiai, which he had not visited in years. In interviews around the time of Documenta, Mekas discussed the work not only as a monument to his hometown but also as an example of how film could offer an intimate view of a life. “I’m spending all my energy on doing something constructive and positive,” he told the Telegraph that year. “Everyone is destroying libraries and I’m building one.”

[ad_2]

Source link