[ad_1]

John Giorno.

COURTESY SPERONE WESTWATER

John Giorno, who blazed an inimitable, almost-impossible-to-believe path through the most venturesome regions of poetry, art, music, and activism in postwar New York, died on Friday. He was 82. His death was confirmed by his galleries Almine Rech and Sperone Westwater.

Giorno was one of those extremely rare figures who would have had an admired career, and earned a place in the canon, even if he had only pursued one of his myriad interests. He wrote gloriously explicit poetry in the 1960s that foregrounded his homosexuality, gave frenetic performances around the world, painted bewitching text paintings, organized efforts to care for colleagues battling HIV/AIDS, and was an early convert in the United States to Tibetan Buddhism and meditation.

The central project of Giorno’s life was dramatically expanding the boundaries of poetry, and—at least equally as important for him—revolutionizing the methods by which it could be presented and distributed. His immersion in the thriving New York avant-garde scene of the 1960s provided him inspiration. He once told the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, recalling his mindset at the time, “It occurred to me that poetry was 75 years behind painting and sculpture and dance and music.” And so he got to work catching it up.

Installation view of “John Giorno: Perfect Flowers” at Elizabeth Dee in New York in 2017.

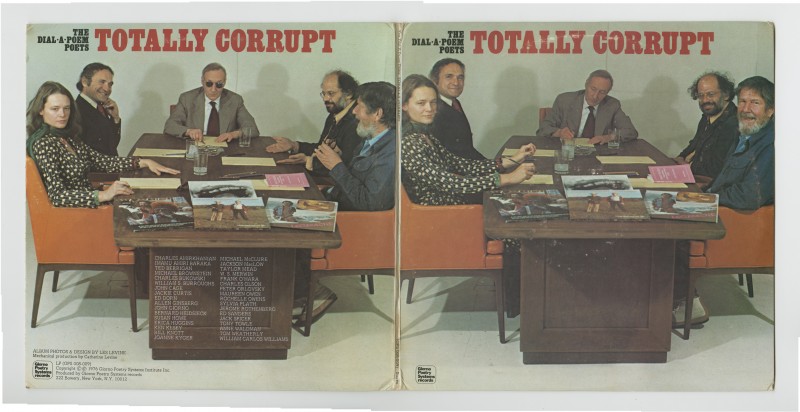

Perhaps no Giorno piece exemplifies his precedent-busting sensibilities as succinctly as Dial-A-Poem, a service he started in late 1967. It allowed anyone with access to a telephone to call a number—advertised in the New York Times, among other places—and hear short poems by the likes of Joe Brainard, John Cage, and Anne Waldman, as well as speeches and texts on civil rights and opposing the Vietnam War. In 1970, the curator Kynaston McShine included the piece in “Information,” his seminal survey of conceptual art.

There were “poems with sexual images, straight, or preferably gay, as I’m a gay man; and as political activism,” Giorno told Obrist. “It seems strange that, in 1968, everything was still externally puritanical.”

John Giorno was born in 1934 in New York and attended James Madison High School—the alma mater of both Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (she graduated before Giorno) and Senator Bernie Sanders (after), the New York Post has noted. Instructed by a teacher to write a poem at the age of 14, Giorno found it “blissful,” he told the tabloid. He kept at it.

Giorno loved New York, and opted to stay in the city for college, attending Columbia University and graduating in 1958. “I read a copy of Howl on spring break ’56,” he told the Brooklyn Rail. “It blew my mind.” Its author, Allen Ginsberg, would eventually become a friend, like so many of the pioneering cultural figures of his time.

But though he would later become an exemplar of urban bohemia, Giorno actually did a stint as a stockbroker after college. (His parents had cut off his allowance.) That didn’t last.

By the early 1960s, he had thrown himself fully into the small downtown art scene, but he bristled at the constraints of the period. “There were all these gay artists, but they didn’t allow gay images in their work, nor was their gayness reflected in their work because it would have been the kiss of death,” he told Frieze in 2015. “You couldn’t be a gay artist at that time.”

Giorno Poetry Systems, The Dial-A-Poem Poets: Totally Corrupt GPS 008-009, 1976.

COURTESY GIORNO POETRY SYSTEMS

Giorno took a different tack in his work, and in 1964, he delivered one of his essential pieces, “Pornographic Poem,” which begins: “Seven Cuban / army officers / in exile / were at me / all night.” The piece was later released as a record, with contemporaries like the poet and critic Peter Schjeldahl, artist Brice Marden, and others reading his words.

The next year, 1965, would be pivotal for Giorno. He met the writer William Burroughs and artist Brion Gysin—future lovers and artistic collaborators for him at various points. At Gysin’s suggestion, he and Giorno recorded sounds in the New York City subway, and they spliced them together to make a sound piece. Giorno also moved into the Bunker, the storied art-filled building at 222 Bowery that he called home for the rest of his life. And that same year he started Giorno Poetry Systems, intent on bringing experimental poetry and sound to wider audiences through seemingly any means necessary. Its legacy includes Dial-A-Poem and dozens of record albums, which he sold through retailers and distributed to radio stations.

In the 1980s, Giorno and poets who recorded with GPS used their royalties to provide emergency grants to artists with AIDS. “I had already spent ten years raising money for political causes,” Giorno told Frieze, “but I realized by 1982 that the only thing people with AIDS needed was money for their expenses, direct help.” (Through what became known as the AIDS Treatment Project, Giorno said that he wanted to help people with AIDS “with promiscuous love and compassion, just like when we fucked. We had lots of people helping to lead us to people needing help.”)

The years after meeting Gysin were ones of spiritual searching and travel for Giorno, both physical and mental. The two tripped on LSD 34 times in the Chelsea Hotel in Manhattan, and the poet told Tricycle that he at one point experienced “a fleeting glimpse of the relative, that only mirrors the absolute. … Brion and LSD changed my life.” He began to meditate and at the start of the 1970s traveled to India, studying with Dudjom Rinpoche and converting to Tibetan Buddhism, bringing what he learned back to the U.S.

Endlessly curious, Giorno always seemed to find himself in the right place at the right time, meeting and connecting with forward-thinking people. He helped push art and ideas along—sometimes as a collaborator, other times as a subject. Perhaps most famously, he is the naked man resting in the 5-hour-long film Sleep (1963), which Andy Warhol, his lover at the time, shot over a number of weeks. (The piece is included in the new hang of the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection in New York.)

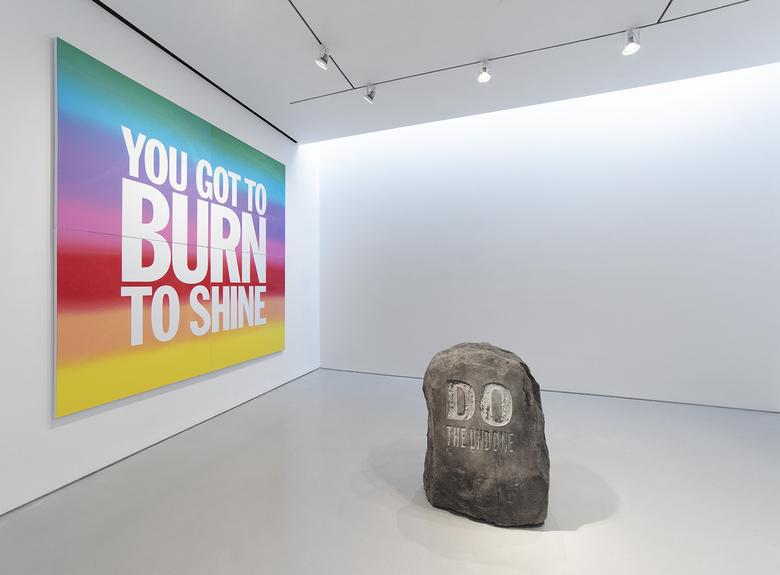

Installation view of “John Giorno: Do the Undone” at Sperone Westwater in New York, on view through October 26.

COURTESY SPERONE WESTWATER

Speaking with the artist Rob Pruitt a few years ago, Giorno said that he was surprised to find that his ass had made an appearance in the film. His role, quite simply, had been to sleep, he explained. “I stayed out of it, because I’m not a filmmaker, I’m a poet, and I know that it’s always best to leave the filmmaker alone and stay out of it.”

The captivating, charismatic performances that Giorno gave of his poetry throughout his career earned him a devoted following. Such live events were a key part of his process. “If there are 500 people in the audience, it’s like 500 mirrors looking at themselves,” he told the journalist Marcus Boon in 2008. “People think that when a poem works, it’s because of the lines of a great poet—Baudelaire, T. S. Eliot, Whitman, or whoever—but it’s not so. The lines, when they magically work, are the reflection of your mind.”

Over the past couple decades, Giorno increasingly focused his efforts in the visual art world, and in 2015 he was the subject of a sprawling retrospective titled “I ♥︎ John Giorno” that was organized by his husband, artist Ugo Rondinone, at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, which traveled two years later to 13 alternative spaces in New York. It was the latest milestone in a career that was enjoying a late-career renaissance.

“We are proud and honored to have worked closely with this incredible artist, poet, and performer,” Almine Rech gallery said in a statement today.

“John was filled with extraordinary generosity, presence, and humor, not to mention a deep drive to be part of conversations and collaborations with artists,” the dealer Elizabeth Dee, who showed him in New York, said in an email, adding that, “In terms of art and the multi-generational influence John had, both as muse and mentor, we may never see the likes of someone like him again.”

Installation view of ‘UGO RONDINONE : I ♥ JOHN GIORNO’ at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris in 2015.

COURTESY PALAIS DE TOKYO

Giorno currently has a show at Sperone Westwater in New York—just a block away from his home at 222 Bowery. “It has been a privilege and a pleasure to work with John,” Angela Westwater, the gallery’s cofounder, said in a statement. “I first experienced Dial-A-Poem in the ‘Information’ show at MoMA, so working closely with him for our exhibition has been rewarding beyond expectation.” And she referred to “his infinite creativity and zest for life.”

The Sperone Westwater show runs through October 26, and features a spread of the paintings that Giorno has became best known for in his last years. Their backgrounds are brightly colored gradients on top of which he has floated crystalline texts in bright white letters: in them, poetry is again finding new audiences through new means. The phrases include “YOU GOT TO BURN TO SHINE,” “WE GAVE A PARTY FOR THE GODS AND THE GODS ALL CAME,” and “DO THE UNDONE.”

That last line, which also appears on a stone sculpture in the exhibition, is an ethos to which Giorno was deeply committed. “I’m not so aggressive about making things happen,” he told me when I visited him at the Bunker a number of years ago and asked about how his first art shows had come about. “I do everything. I’ve spent a lifetime doing everything. I just sort of let it happen.”

[ad_2]

Source link