[ad_1]

Getting out of bed is overrated. Johanna Hedva, a Korean-American artist, writer, and musician who is based in Berlin, has long dedicated their work to reframing sleep as not only a means of recuperation, laziness, and escape, but also of generative dreaming, resistance, and refusal. For their sound-based solo exhibition “God Is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce” at Klosterruine, Berlin—continuing through August 3—Hedva has created a playlist comprising readings of their essays along with examples of their music, and pieces by four other composers. Visitors can commune in-person with Hedva’s work, which plays on speakers placed amid the ruins of a thirteenth-century Franciscan monastery, or listen along—from bed, in the car—at www.godsauce.black. Many of the texts are from Hedva’s book Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain, out in September from Sming Sming and Wolfman Books. One textual example is titled “On Lying Still for the Hours of the Afternoon,” another, “A Decade of Sleeping.” In the latter, Hedva states: “I wrote most of this book, maybe all of it . . . in my sleep. . . . I write as soon as I wake, but it is through writing that I fully awaken.” Similarly, their well-known essay “Sick Woman Theory,” written in Los Angeles during the 2016 Black Lives Matter protests, challenges the equation of activism with marching in the streets, reminding us how that notion excludes many chronically ill and disabled people. Below, Hedva talks about moving fluidly between mediums in order to create multiple ways of experiencing a work.

Both the book and the exhibition feature work that you’ve produced over the last ten years. Did any unexpected themes or patterns emerge as you were revisiting your work?

I compiled the book Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain after realizing that there were common themes throughout a decade of my work—sleep, madness, mysticism, the politics of genius, the trouble with gender. I’d never intended the material in Minerva to be a book: instead it sort of assembled and re-assembled itself over a period of seven, eight, nine years, and this mutation, as its own theme, persuaded me that it was of a coherent piece.

Your exhibition—the playlist—can be accessed both in person and remotely. Online, all of the audio is described. How did you approach making accessible art?

Making an exhibition during COVID-19 meant that my primary concern was access. I was thinking about how the work could exist in multiple forms, pushing against the ableist notion that art is best experienced in person. But I didn’t want to just post pictures on a website: I wanted to make the show accessible in a meaningful way. I wanted the work itself to have these different entry points, for the shape-shifting-ness of the pieces to be the blood and spit and bone of the show, rather than an afterthought or ill-fitting exoskeleton. And I wanted to ensure that its physical manifestation was safe to attend: as safe as possible, during a pandemic. I’ve found that access is never perfect; it’s always a mess. Access is not a finished, completed, perfect product to be achieved. It’s living within relationships that are formed and un-formed and re-formed, in all our entanglements and interdependencies.

The show is more or less outdoors: it takes place amid open-air ruins.

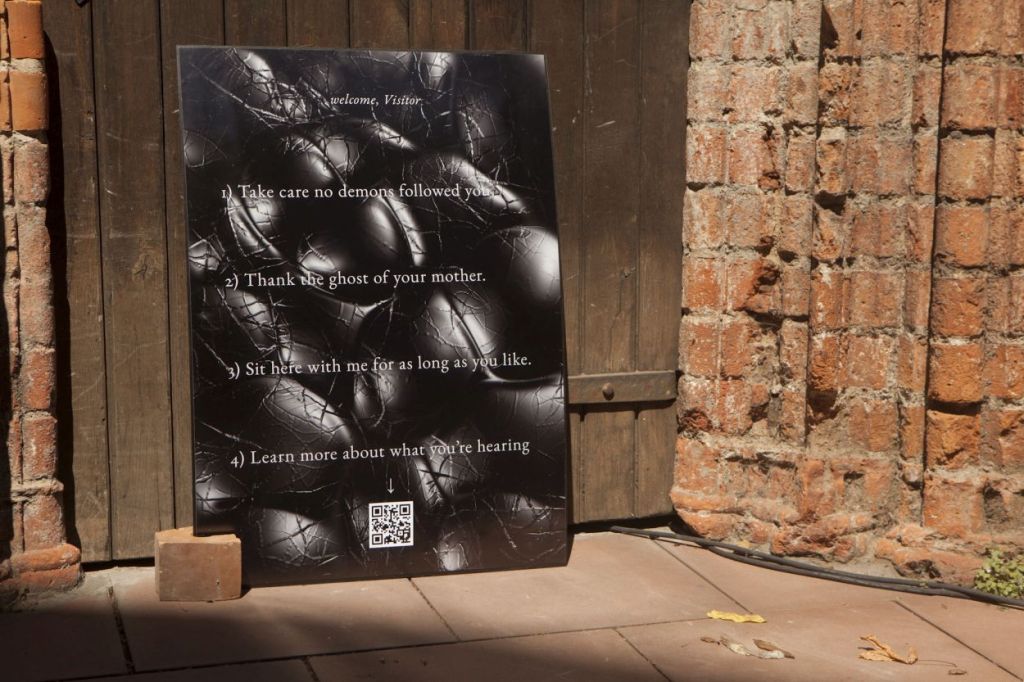

The Klosterruine is a host for ruminations on absence and presence. The site is rather empty—there are only two walls still completely standing. There’s no glass in the windows, and there’s no roof or ceiling—but there’s this striking feeling that it’s teeming with history, ghosts, and energies.

I wanted to make a show that would respond to those conditions: asking if absence is ever really empty, if absence ever truly exists. Where—really—are those who used to be here? And conversely, what exactly do we mean when we speak of presence? Is it only corporal presence, bodies in space? What about presences that can’t be seen?

That’s why I decided to use sound as the show’s primary medium, to reproduce the experience of being surrounded and infested by a presence other than a physical body that you can see.

Photo Juan Saez.

I enjoyed reading the descriptions of your music. It’s refreshing to read sound descriptions by a writer! My favorite is when you describe your voice in the song “Family” as sounding “like a family of ghosts.” Can you talk about the process of describing your songs?

Thank you! Music is, to me, the hardest thing in the world to write about, next to mysticism. How do you describe sound in words? I’m currently working on a book called The Mess, which is about music and mysticism: both of these seem to resist language: they are beyond language, they elude it.

On a more practical level, I had to write many of these descriptions of the songs anyway because I’m working with people remotely to make my new record, Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House. My producer, Randall Dunn, is in New York while I’m in Berlin, and so a lot of our communication about the record has taken place via email or on the phone. It’s been fun, I’m like, “I’m trying to sound like a whale here!” “In this part, I want to sound like an angel in a broken church.”

I consider all of my work, no matter the genre, to be writing. Language makes marks, and I’m the sort of witch who believes that language itself is magic—that through it and because of it, the world is changed.

In the book you document some of your performance works—many of them produced for an audience of one, or a few animals—through written, ex post facto reflections. It sounds like you move between language and other forms—performance, music—because you process everything through writing, and also use it to create the multiple points of entry you mentioned.

For as long as I’ve been making, I’ve been promiscuous in terms of the forms I work in. I tend to get dazzled by what form, media, genre can do: I like thinking of them transforming into each other, trespassing. My friend [experimental writer] Henry Hoke said: “Let your genres bleed into others. Turn your poetry into plays. Turn your novel into a thirty-second song. Turn your journal into fiction.” It’s fun to think of a work in terms of what it is not, what it could be, what it could disguise itself as. Like, if you were trying to smuggle your album into the room of political theory, what outfit would it have to wear?

Your book also includes some reflections on what different forms do. I love the line: “I think theater needs to be arresting. That is, it ought to get you arrested.”

That was in reference to my play Odyssey Odyssey, a 2013 adaptation of Homer’s epic performed in a Honda Odyssey. The cast and I discussed what to do if we were pulled over by the cops. My direction to them was, if at all possible, don’t break character.

[ad_2]

Source link