[ad_1]

Is it a crime to wear a beard?

In this particular moment in time, beards are so common that we perhaps only truly pay attention to them when we are to describe the person who has one. But think some two hundred years back and the village of Fitchburg, Massachusetts – does it make sense now?

No, not really. It was nonsense to Joseph Palmer as well, a man who wore a beard then and there and paid a steep price for it, involuntarily becoming a kind of a pioneer in a fight for a man’s right to have facial hair – and for an America that is rational, rather than not.

While Joe Palmer is now forgotten, his story might live on – mostly through a series of photographs by one Joel Sternfeld. In a heartwarming, trademark way, the celebrated artist pays homage to the man “persecuted for wearing the beard” through portraits of other men who today, in a way thanks to Palmer, don’t even have to think about whether having one might be a problem. His images are accompanied by excerpts from a 1944 recount of the life of Palmer by Stewart Holbrook, another man who tried to preserve his memory.

Joseph Palmer and His Beard

Joe Palmer would have probably been just another man living in New England back in the 19th century, one with a wife and a son, one who one day moved to the village of Fitchburg from a nearby farm. His name and existence would have likely been forgotten, as are most names of the common men. But what Joe Palmer had at that very moment in time was a beard, “almost if not quite the only beard east of the Rocky Mountains, and possibly beyond.”[1]

You see, somehow over the course of centuries before that, America had been gradually losing bearded men, becoming almost wholly free of facial hair by the year 1720.

But when Joseph Palmer came to town in 1830 wearing a beard, he was the first man in almost a century to have it. And as such, he strangely became the target of everyone there, an offender on a great, great scale.

The Man Who Wore “Monstrosity”

Shortly after becoming the resident of Fitchburg, Joe Palmer began encountering trouble. Kids threw stones at him and were rude to his son, Thomas, women avoided him on the street, the windows of his home were broken on several occasions. Even local figures like the pastor and the doctor judged him and tried to get him to shave.

But Palmer was a good man of strong convictions.

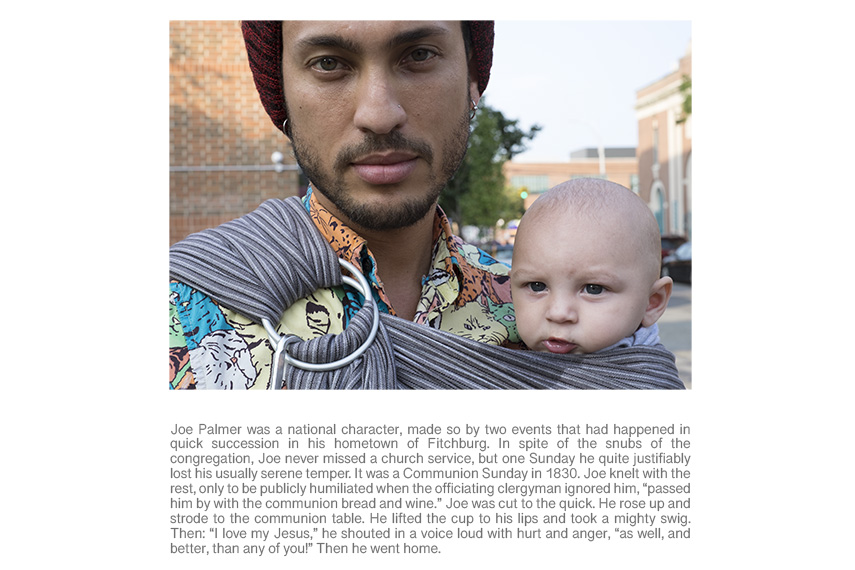

Even though he was snubbed by the church, he never missed the Sunday service, but on one such occasion in 1830, he lost his temper when the clergyman did not pass him the communion bread and wine.

Joe was cut to the quick. He rose up and strode to the communion table. He lifted the cup to his lips and took a mighty swing. Then: ‘I love my Jesus,’ he shouted in a voice loud with hurt and anger, ‘as well, and better, than any of you!”’Then he went home.

A few days later, he was captured by four armed men, who told him that it was the sentiment of the entire town that his beard should come off. With shears, soap, brush and razor, they tried to “get the job done” then and there, but Joe Palmer managed to fight them off with an old jack-knife, later returning home with bruises and his beard intact.

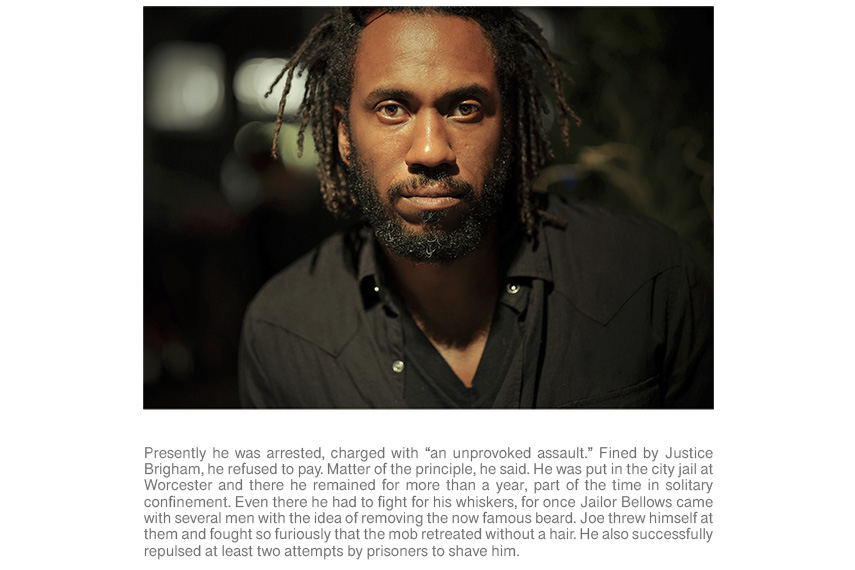

But his peace didn’t last for long, as immediately after, he was arrested and charged with “unprovoked assault”. After refusing to pay the $10 fine on “a matter of the principle”, Joe Palmer was put in the city jail at Worcester, and there, he remained for more than a year, part of the time in solitary condiment as well.

The Bearded Prisoner of Worcester

In a way, it doesn’t come as a surprise that Joe Palmer was not left alone while in prison either; even the jailor tried to forcefully shave his face one time, while other prisoners attempted to do it too at least twice more.

But he didn’t spend his time in prison in vain. He wrote letters, which he smuggled out a window to his son, which were then published in the newspapers, first in the local ones and then the ones covering wider areas. In fact, people all over the state of Massachusetts read his story and reflected on it.

Eventually, the sheriff came to realize he had a martyr on his hands and offer Joe his freedom. But to everyone’s shock, Joe Palmer refused. ”I won’t walk one single step toward freedom!” he would exclaim through the bars, until one day, the officers picked him up together with his chair and carried him out to the street.

Finally, Joe Palmer could carry on with his life, as no one dared touching him or his beard ever again.

A Bearded Hero

The beard of Joseph Palmer, perhaps even more than the man wearing it, became famous as far away as New York and Philadelphia. As a way to best use his freedom, and his newfound popularity, Palmer became a part of the intellectual circle, advocating for the abolition of slavery and attending literary and reform meetings. He even became a part of the radical and unsuccessful commune called Fruitlands. During his life, he met Emerson, Thoreau, Alcott and Channing, among others.

Toward the end of his life in 1875, beards were “back in fashion” again – but his own, of course, was the one that had special meaning. Joe Palmer was a good, honest and kind man, a man whose principles almost cost him his life, but had also kept him on the right path.

Joel Sternfeld and his Visual Homage

Known for chronicling roadside America in the style of the great Modernist photographers of the 1920s and 30s, Joel Sternfeld created To Joseph Palmer portfolio, featuring poignant portraits of men with beards accompanied by pieces of aforementioned text by Stewart Holbrook.

Although it is the beard that is common for all the men in Sternfeld’s photographs, their silent protagonist is Joe Palmer, whose remarkable yet still a bit unbelievable story was told to each of them. Thus, their own beards now stand as part of a victory, and the right of all people to be free in their practices and beliefs that hurt no one.

Joel Sternfeld’s To Joseph Palmer was shown at Buchmann Galerie in Berlin between November 2017 and February 2018. It also represents another one of his projects in which the photographer combines imagery with text, having previously done so for On This Site, Treading on Kings, When it Changed and Sweet Earth. Although a pioneer of color photography, Sternfeld never makes color arbitrary in his work; rather ” it functions in highly sophisticated ways to connect elements and resonate emotion.”[2]

Editors’ Tip: Joel Sternfeld: American Prospects

Originally published in 1987, Joel Sternfeld’s now-classic view of America is here remastered, redesigned and reprinted at a larger, brighter, truer scale. Finally, photography and offset printing techniques have caught up with Sternfeld’s eye, and this new edition of American Prospects succeeds in presenting Sternfeld’s most seminal work as it has always meant to be shown. A specially-commissioned essay by Kerry Brougher, Chief Curator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, considers the historical context in which Sternfeld was working and the pivotal role that American Prospects has played in the course of contemporary filmmaking and art photography.

Editors’ Tip: Joel Sternfeld: Stranger Passing

Over a period of 15 years, Joel Sternfeld traveled across America and took portrait photographs that form, in Douglas R. Nickel’s words, “an intelligent, unscientific, interpretive sampling of what Americans looked like at the century’s end.” Unlike historical portraits which represent significant people in staged surroundings, Sternfeld’s subjects are uncannily normal: a banker having an evening meal, a teenager collecting shopping carts in a parking lot, a homeless man holding his bedding. Using August Sander’s classic photograph of three peasants on their way to a dance as a starting point, Sternfeld employed a conceptual strategy that amounts to a new theory of the portrait, which might be termed The Circumstantial Portrait. What happens when we encounter the other in the midst of a circumstance? What presumptions, if any, are valid? What, if anything, can be known of the other from a photographic portrait?

References:

- Holbrook, S., The Beard of Joseph Palmer, The Phi Beta Kappa Society, 1944

- Unknown, A Biography of Joel Sternfeld, Getty [March 20, 2018]

Featured image: Joel Sternfeld – Details from To Joseph Palmer, 2017. Series of 25 archival ink jet prints. Each: 14 x 17.5 inches (35.5 x 44.5 cm). © Joel Sternfeld; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

[ad_2]

Source link