[ad_1]

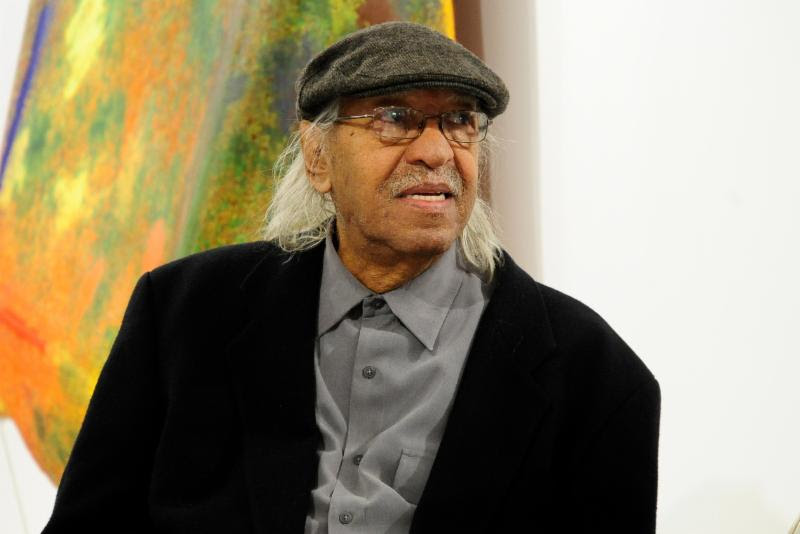

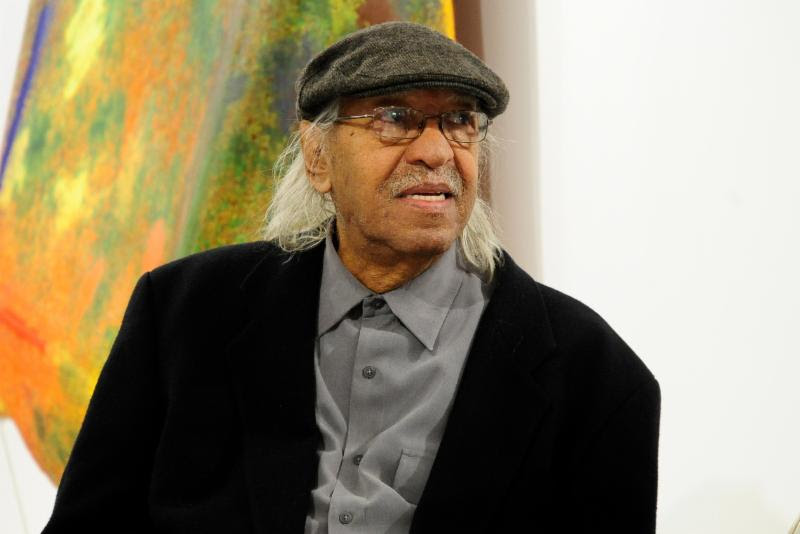

Overstreet.

COURTESY ERIC FIRESTONE GALLERY

‘My paintings don’t let the onlooker glance over them, but rather take them deeply into them and let them out—many times by different routes,” the artist Joe Overstreet once said, describing viewing experiences that can be variously harrowing and exhilarating. “These trips are taken sometimes subtly and sometimes suddenly.”

Over the course of a six-decade career that cut across artistic movements and unflinchingly addressed issues of racism and inequality, Overstreet established himself not only as one of the signal painters of postwar American art, but also as a vital organizer. As an African-American man working in a cultural sphere that has long marginalized non-white artists, he helped to create exhibiting opportunities for numerous artists of diverse backgrounds at Kenkeleba House, the arts space he cofounded on Manhattan’s Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1974.

Overstreet’s death on Tuesday night in New York at the age of 85, which was confirmed by Eric Firestone Gallery, his representative in New York, marks the end of a trailblazing life, and it comes amid renewed interest—both scholarly and commercial—in the artist’s relentlessly innovative work, resulting from museum exhibitions focused on the work of African-American artists and other artists of color.

Joe Overstreet, The New Jemima, 1964/1970.

COURTESY MENIL COLLECTION

Because Overstreet worked in a wide variety of modes, his art resists any simple summation. But he is best known for his incisive political works of the 1960s and his “Flight Patterns,” the gloriously colorful abstract pieces—inspired by Tantric drawings and Navajo sand painting—that he began making in 1970 on shaped canvases that he attached to walls, floors, and ceilings by running ropes through holes at their edges so that they appear to be floating or flying.

“I was making nomadic art, and I could roll it up and travel,” Overstreet said of those stretcher-free works. “We had survived with our art by rolling it up and moving it all over. I felt like a nomad myself, with all the insensitivity in America.”

Joe Wesley Overstreet was born in 1933 in the small town of Conehatta, Mississippi, about 60 miles east of Jackson, and wanted to be a painter from an early age. Speaking with an interviewer a few years ago, Overstreet noted that he was then 78—and quickly added, “I’ve been trying to be a painter for probably 70 of those 78 years.” He credited his rural upbringing with shaping the direction of his work. “Because I had experienced beauty and freedom in nature, I could recognize it in art,” he told Barry Schwabsky in a 1996 profile in the New York Times.

His family moved frequently in his youth and eventually settled in Berkeley, California, making the journey to there from the South with a caravan of other black families in an attempt to ensure their safety. Overstreet went to high school in Oakland, then worked in the Merchant Marine part-time while studying at Contra Costa College in Richmond, California and the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute), learning from pioneering black artists like Sargent Johnson and Raymond Howell. He moved to Los Angeles in 1955 and began working as an animator for Walt Disney, before decamping to New York to pursue art.

Overstreet quickly fell into its bustling art scene, spending time at the famed Cedar Tavern, working in an Abstract-Expressionist and Color Field styles, and becoming close with peers like Willem de Kooning, Hale Woodruff, and Romare Bearden. (As one story goes, de Kooning gave Overstreet some of his work to sell, to help him make ends meet.) In 1962, he moved into a downtown building that the jazz musician Eric Dolphy also called home, and during that same decade worked as art director of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School that was founded by LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka).

Installation view of “Joe Overstreet, Innovation of Flight: Paintings 1967-72” at Eric Firestone Gallery, 2018.

COURTESY ERIC FIRESTONE GALLERY

Visiting sculptor John Chamberlain’s studio’s one day in the early 1960s, Overstreet picked up a magazine featuring a photograph of a lynching of young black men, leading him to paint one of his best-known works, Strange Fruit (ca. 1965), a chilling semi-abstraction that shows a pair of legs with sneakers hanging down from the top of the picture. “I felt the most ridiculous anger I’ve ever felt, seeing this innocent kid they had maimed and disfigured and the neck was stretched,” he said, adding in another interview that one of the figures reminded him of his brother. “That photograph and the Billie Holiday song was probably what brought the painting together for me.”

Around that same period, he painted the first version of one his most indelible images, The New Jemima (1964), for which he placed a machine gun in the hands of the racist mammy figure identified in the title. “I read in a magazine that Nancy Green, who was born in slavery in Kentucky, cooked around a million pancakes at the 1893 Chicago World’s Exposition in order to save a pancake flour company,” he said in an interview with Tate about that work. “She made me think of my grandmother, my mother, and I thought she must have been very tired. And I knew Jemima was tired of that role.” Overstreet was also active in the civil rights movement by demonstrating and participating in shows that aimed to raise money for those efforts.

After a teaching job took him back to the Bay Area, Overstreet returned to New York in 1974, where he met his future wife, the artist Corrine Jennings. Together with the writer Samuel C. Floyd they founded Kenkeleba House on East 2nd Street in the East Village of Manhattan, which became a hotbed of activity for artists of African, Latino, Asian, and Native American descent, including David Hammons, Rose Piper, and Norman Lewis. (The name came from the Seh-Haw plant of West Africa, which is used for spiritual and healing purposes.) “We are the only downtown gallery that focuses on black artists’ work,” Jennings told Black Enterprise in 1985.

While continuing to be deeply involved with Kenkeleba House, Overstreet experimented widely in series that were often informed by his broad travels. His “Storyville” paintings of the late 1980s look at the history of jazz in New Orleans, incorporating narrative and figurative elements, and his “Door of No Return” paintings—abstractions that pair sophisticated rhythmic markings with elements of sacred geometry—were informed by a visit to the House of Slaves on Gorée Island in Senegal, from which enslaved people were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1996, Overstreet was the subject of a retrospective at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton, and had solo shows at the Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York, and the Aljira Contemporary Art Center in Newark New Jersey. “I’ve been intensely involved in the struggle to find out what I could accomplish,” he said in a profile that year. “The achievement always falls short. You’re only ever 10 percent there. Maybe Leonardo or van Gogh got to 30 percent.”

Overstreet pursued that struggle into his 80s, working actively, and his reputation has grown over the past decade following appearances in shows like “Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980,” which originated at the Hammer Museum in L.A. in 2011, and “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” which began at Tate Modern in London in 2017. His work is held by the Menil Collection in Houston, the Brooklyn Museum, and other museums, but it still remains under-represented in many leading arts institutions.

“A lot of inspirations we have are fleeting ideas,” Overstreet said in a 2009 interview. He was discussing what led him to paint Strange Fruit, but his explanation could serve as a succinct summary of the effect of his richly varied art. He went on, “We get a glimpse, a slight glimpse, and that’s all we need sometimes to open up a whole universe for us.”

[ad_2]

Source link