[ad_1]

Joe Biden’s attempt to defend his stance on busing at Thursday’s debate has created even more problems for the former vice president, calling into question what he believes the federal government’s role should be in ensuring racial justice.

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) dominated the second night of the presidential debate in Miami, in large part due to her confrontation with Biden. She told him that she found it personally hurtful that he boasted about working with segregationist senators on issues like busing, the imperfect and controversial means of desegregating public schools by transporting children to various schools farther away than their neighborhood ones.

Harris, the second black woman ever elected to the U.S. Senate, said she was a beneficiary of busing.

Biden refused to apologize for his stance on busing, on which he made a name for himself in the 1970s. Instead, he clarified that he didn’t oppose all busing, just federal efforts to force busing.

“What I opposed is busing ordered by the Department of Education. That’s what I opposed,” he said, adding that it was fine when it was a “local decision.”

I’ve gotten to the point where I think our only recourse to eliminate busing may be a constitutional amendment.

Joe Biden, 1975

But that attempt to make the situation better has, in many ways, made it worse for Biden.

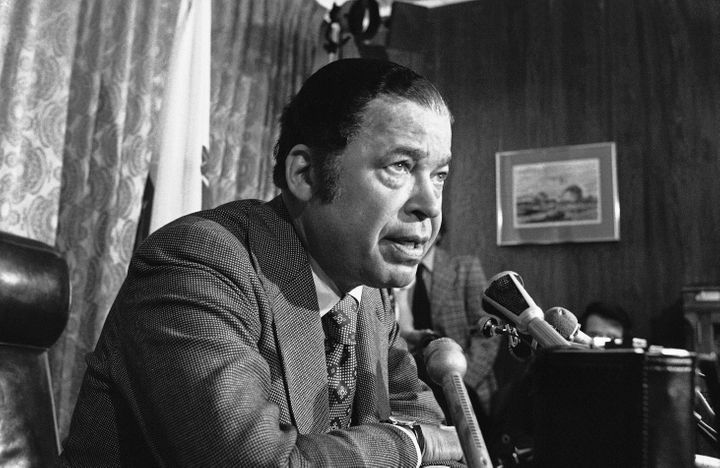

On Saturday, MSNBC host Al Sharpton told a group of civil rights activists how troubling he found Biden’s answer to be:

The thing that was so egregious about Joe Biden’s answer to Kamala Harris the other night was when he said that, ‘Yes, you were bused because the local school board voted for that. That was alright. I was against federal intervention.’

That meant states’ rights. The whole fight of the Civil War was a strong national government against states having the right to vote for slavery state by state. The whole fight around segregation was whether states had the right to say you could sit in the front of the bus or not, or go to a hotel or not. States’ rights [means] opposing a strong federal government that protects the citizens, particularly minorities.

After the debate on Thursday, Harris, too, said she was “surprised” by Biden’s answer.

“We have so many examples in history where states have limited or restricted people’s civil rights. … We have certain values that are national standards, and we’re not going to let states compromise that,” she said.

And Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), the only other competitive black candidate in the 2020 race, said he was floored by Biden’s response. (Booker debated on Wednesday night, since the large field of candidates was divided into two nights.)

“I think that anybody that knows our painful history knows that on voting rights, on civil rights, on the protections from hate crimes, African Americans and many other groups in this country have had to turn to the federal government to intervene because there were states that were violating those rights,” he said on CNN.

In the short time he’s been running, Biden has consistently faced questions on his record, which spanned decades in the Senate. From busing to abortion to Anita Hill to criminal justice, Biden has been called to account for views and statements that are out of line with where the party is today.

His campaign has urged people to look forward, toward what he would do if he defeats Trump, but it’s a tough line to hold when much of his campaign is built on his experience in government. Still, Biden continues to maintain a considerable amount of support from black voters.

Biden initially supported busing during his 1972 Senate campaign, but once in office, he became the chamber’s leading liberal voice against it.

“I oppose busing. It’s an asinine concept, the utility of which has never been proven to me,” he said in a 1975 interview. “I’ve gotten to the point where I think our only recourse to eliminate busing may be a constitutional amendment.”

“The new integration plans being offered are really just quota-systems to assure a certain number of blacks, Chicanos, or whatever in each school,” he added. “That, to me, is the most racist concept you can come up with; what it says is, ’In order for your child with curly black hair, brown eyes and dark skin to be able to learn anything, he needs to sit next to my blond-haired, blue-eyed son.’ That’s racist! Who the hell do we think we are, that the only way a black man or woman can learn is if they rub shoulders with my white child?”

Biden’s shift reflected the politics of his white constituents who were livid about a court-ordered integration plan in Wilmington, Delaware.

Biden’s campaign has taken a two-pronged approach to defending his record since the debate.

His spokespeople have pointed to his more recent record on civil rights, supporting measures like the Voting Rights Act and, of course, his partnership with former President Barack Obama.

“Vice President Biden stood shoulder to shoulder with President Obama for eight years in the White House,” Biden campaign spokesperson Symone Sanders told reporters after the debate in Miami. “And so the idea that he is somehow out of step with the Democratic Party when it comes to civil rights ― I just don’t think it sticks and I don’t think it will stick with the voters.”

But his campaign has also defended his stance on the merits, arguing that African American civil rights leaders were not universally in agreement about busing and that, in fact, busing did not achieve its goals.

“Busing was a remedy that at the time many were saying was not ― many in the African American community, many in the civil rights community ― was not the best way to integrate schools,” Biden campaign communications director Kate Bedingfield said on MSNBC on Friday. “And frankly, that’s been borne out today. I think if we have an honest discussion about the impacts of busing, there are a lot of people who would say it hasn’t been the best remedy to integrate schools.”

The story of support for busing is more complicated. Few people thought busing was the “best way” to integrate schools. Instead, it was usually viewed as a last resort.

For Sen. Edward Brooke (R-Mass.) ― the first black person elected to the chamber by popular vote and a supporter of busing who went up against Biden on the issue ― busing “was the best thing that we had to at least desegregate the schools at that time in our history.”

Many of the anti-busing measures Biden supported drew bitter opposition from the major civil rights organizations. The NAACP, for example, lobbied hard to stop an amendment Biden introduced in 1977 that would have barred the use of federal funds for busing.

Biden also supported an amendment from segregationist Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) that would have barred the federal government from collecting data on the race of students and teachers. When that measure failed, Biden crafted his own amendment barring federal funding for the purposes of helping school districts “assign teachers or students to schools … for reasons of race.” With Biden, rather than Helms, leading the charge, other liberal Democrats were more comfortable voicing their support and it passed the Senate.

By limiting the federal government’s authority to shape school integration, liberals feared at the time that Biden was setting a far-reaching precedent. The amendment was particularly upsetting to Brooke, who called it “the greatest symbolic defeat for civil rights since 1964.”

And at least some of the African American opposition to busing came from black nationalists who thought culturally sensitive curricula and community self-sufficiency were surer routes to black liberation. For example, one black opponent of busing in San Francisco proposed granting African American parts of the city their own independent school board if they could not get the autonomy they desired in the confines of the present system.

In addition, contrary to what Bedingfield said about its effectiveness, there is evidence that busing achieved its goals in many parts of the country. Nationwide school segregation dropped from nearly two-thirds of black students in segregated schools to about one-third over the period from 1968 to 1980, after busing became a tool available to the federal government. The Northeast was the only region where school segregation rose during that period, according to a 1983 study by the Joint Center for Political Studies.

In a speech to the Rainbow PUSH Coalition in Chicago on Friday, Biden emphasized that he had always supported federally imposed busing to overcome official, rather than de facto, school segregation.

Biden’s position was essentially that busing was acceptable in cases of deliberate segregation ― as in the South with its Jim Crow segregation laws ― but not when there was “de facto” segregation (as in Northern cities, where, as the thinking went, many neighborhoods just happened to be all white or all black).

But of course, that segregation in Northern cities was often just as deliberate ― through such discriminatory real estate practices as redlining ― even if it was less out in the open.

“In many cities, the ‘neighborhood school’ — itself a product of redlining, housing segregation, and discriminatory school transfer policies — remains sacrosanct. But we forget that through the 1960s and 1970s, local school boards and urban whites often resisted every other attempt at school and housing integration,” Jason Sokol, an associate professor of history at the University of New Hampshire, wrote in Politico in 2015. “With their resistance, they narrowed the options down to two: busing or segregation.”

But as Sharpton’s remarks attest, it is the broader philosophical approach that Biden signaled approval of ― one that emphasizes states’ rights and local control as opposed to federal enforcement of civil rights ― that could generate the biggest problems for him on the campaign trail.

After the debate, Sanders, the Biden spokeswoman, declined to directly answer a question from NBC News about whether claiming the mantle of states’ rights was really a “durable” defense of the policy.

“If you want to put the vice president’s record on civil rights up against anyone on that stage,” she said, “he’ll stand the test of time.”

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link