Jean Dubuffet, one of the most famous European artists of the postwar era, had an imagination that knew no bounds. In his rough-hewn paintings, drawings, and sculptures ranging from abstraction to childlike figuration, he envisioned altered states in which humanity existed in a form that he believed was closer to its origins. A ceaseless experimenter in the way of materials and forms, he advocated for self-taught or “outsider” practitioners in the field.

These days, Dubuffet may be best known for his large-scale sculptures, which resemble masses of white organic forms sharply outlined in black. He had intended for Le cirque (1970) to be among his monumental ones, but it was never fully realized in a large-scale format—until now. Starting on September 18, Pace Gallery will show a newly fabricated version of Le cirque in its New York gallery. “He both imagined that these things eventually would become physically real and acknowledged that that was never even required,” Oliver Shultz, Pace’s curatorial director, said of Le cirque and other small-scale models by Dubuffet in an interview with ARTnews. “In essence, they already exist at large scale in your mind, and that completely licenses the fabrication of them in reality. So, it’s also just exciting to be able to complete or play out this final stage in what Dubuffet imagined 50 years ago.”

On the occasion of a new fabrication of Le cirque, below is a look back at Dubuffet’s long and varied career.

Dubuffet began his career as an artist in the middle of his life.

Born in Le Havre, France, in 1901, Dubuffet did not dedicate himself to his art practice until age 41, having been dismissed from the French meteorological corps and subsequently working as a wine merchant. At age 17, he did a stint at the Académie Julian in Paris, studying painting, but it was not until 1944 that the artist had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie René Drouin in Paris in 1944, and he got his first solo show in New York at the Pierre Matisse Gallery three years later. According to a New York Times obituary for the artist, Dubuffet’s solo debut in Paris “caused an uproar of a kind that was to become ever more familiar over the next few years.”

The artist coins the term “art brut”—and rocks the Paris art scene.

During the 1940s, the artist maintained relationships with French writers like André Breton, Georges Limbour, and Jean Paulhan, and he became a pioneer of “art brut,” or “raw art,” a term that he coined to denote works that drew on the aesthetic of works by prisoners, children, and people with mental illness. For Dubuffet, these works existed in opposition to high modernism, which prized itself on rigid notions of artistic genius. (More recently, scholars have criticized Dubuffet’s intentions, alleging that he aimed to demean or essentialize works by non-Western and disabled artists.) Works from the so-called “art brut” movement forewent artistic trends and academic conventions in favor of idiosyncratic figures and forms that, according to Dubuffet, could reveal details about the makeup of an individual’s subconscious. “I have a great interest in madness, and I am convinced art has much to do with madness,” Dubuffet said of his creative philosophy in 1952. A collector of pieces by self-taught artists, Dubuffet outlined the virtues of Art Brut in a manifesto for a 1949 exhibition of such works at Galerie René Drouin in Paris.

Jean Dubuffet, Offres galantes, 1967, vinyl on canvas.

© 2020 Jean Dubuffet/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

The artist favors abstraction in the 1950s.

Many of the artist’s paintings from the 1940s tended toward figurative views of cities and countrysides. He created numerous paintings and lithographs depicting scenes inside the Parisian metro, as well as views of city life in the French capital, cyclists navigating country roads, performances by jazz musicians, and farmers at work. The style of these often vibrantly colored pieces was characterized by playful treatments of scale and flattened perspectives. In the following decade, a year of which he spent living in New York, Dubuffet undertook more intense investigations of materials and modes of abstraction. He employed materials like cement, foil, tar, gravel, and more in his work, a practice that, combined with textural experimentations in his works on canvas, represented a blurring of the boundary between painting and sculpture that would inform his future endeavors. Soil Ornamented with Vegetation, Dead Leaves, Pebbles, Diverse Debris, an oil and collage work from 1956, features intricate, interlocking constellations of shapes rendered in subdued tones. Dubuffet’s multifarious sculptural works from the 1950s sometimes hinted at figuration, as with The Ragman (1954), though oftentimes, as with Le Mentonneux (1959) or The Magician (1954), he favored ineffability.

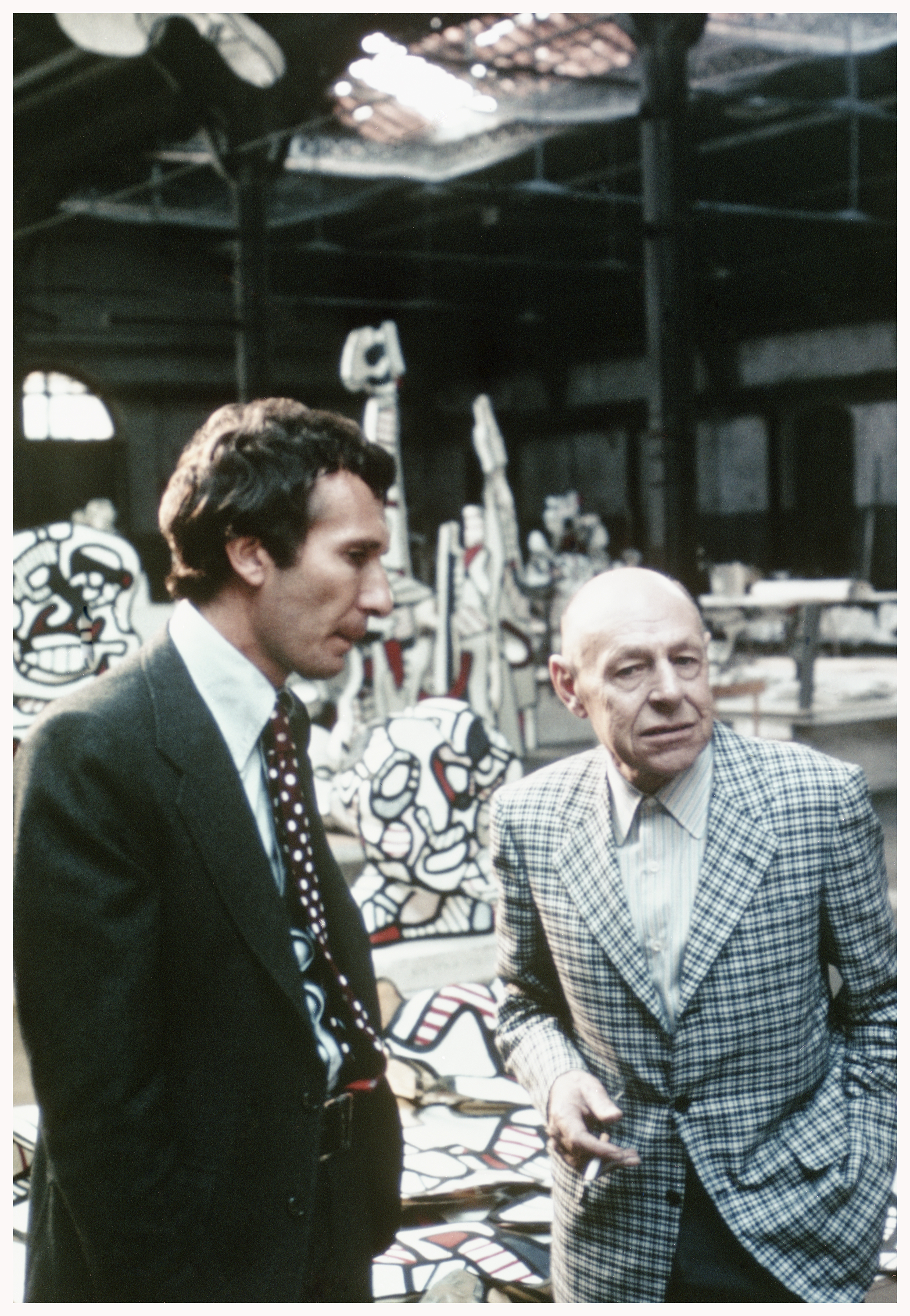

Arne Glimcher and Jean Dubuffet.

Courtesy Pace Gallery

Dubuffet’s star ascends with international exhibitions during the 1950s and 1960s.

The artist got his first retrospective at the Cercle Volney in Paris in 1954, and his first museum retrospective followed in 1957, at the Schlo Morsbroich, which is now known as the Museum Morsbroich, in Germany. During the 1960s he had major showings at the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Palazzo Grassi in Venice, Italy, and Tate in London. Dubuffet also had his first exhibition with Pace Gallery in 1968 after meeting the enterprise’s founder, Arne Glimcher, in Paris in 1966. This was also a period of creative triumphs for the artist, who began work on his famed “Hourloupe” cycle, which comprises paintings, drawings, panels, and sculptural and architectural installations, in 1962.

A 2019 fashion show underneath Dubuffet’s Group of Four Trees in New York.

AP Photo/Mary Altaffer

Many of the artist’s monumental creations are associated with his “Hourloupe” cycle.

Dubuffet’s “Hourloupe” cycle lasted until 1974, and it yielded some of his best known large-scale works. One of the most famous works of his career, an animated painting consisting of 20 madcap costumes worn by performers, was Coucou Bazar, which premiered in New York in 1973. In 1972, the 43-foot-tall fiberglas sculpture Group of Four Trees, which had been commissioned by David Rockefeller in 1969, was installed on Chase Manhattan Plaza in New York. Two years later, in 1974, the artist unveiled his Jardin d’émail, an immersive and interactive environment designed for the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands that underwent a major restoration in 2020. Similar to his “Simulacres,” a group of black-and-white sculptures that debuted at another solo exhibition of Dubuffet’s work at Pace in 1970, Group of Four Trees and Jardin d’émail both feature undulating black lines and shapes atop white sculptural forms. Such formal qualities can also be found in Le cirque, a small-scale model for which the artist created shortly after that 1970 showing at Pace.

In progress view of Jean Dubuffet’s Le cirque, 1970, polyurethane paint on epoxy, with original maquette in foreground.

© 2020 Jean Dubuffet/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Le cirque hasn’t existed on a monumental scale until now.

The artist constructed the 1970 model for Le cirque by arranging five elements from his existing sculpture Eléments d’Architecture Contorsionniste (1969) in a new formation, photographing the configuration, and noting measurement specifications for how large each part would be. Polaroids with those technical specifications—for Le cirque and other modeled arrangements envisioned for large-scale fabrication—were kept in a studio album maintained by the artist. Dubuffet once said that, through such rearrangements of existing pieces, “an environment is formed, consisting of mental elaborations and subsequently a new kind of architecture.” The Dubuffet Foundation and a studio assistant who worked with the artist during his lifetime have, for the first time ever, fabricated Le cirque on a large-scale according to Dubuffet’s model.

In progress view of Jean Dubuffet’s Le cirque, 1970, polyurethane paint on epoxy.

© 2020 Jean Dubuffet/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

The new fabrication exemplifies Dubuffet’s interest in creating distinct environments.

Shultz, curatorial director of Pace, explained that, Le cirque, like other works by Dubuffet, represents “some kind of hybrid between architecture that you move through, that you inhabit, that you become a part of.” The installation, which features biomorphic shapes and lines, wraps around viewers to create what Dubuffet intended as a “lived experience of sensation and form as it comes to us before language, and, in the end, constitutes its own kind of language,” Shultz said. Le cirque, which measures 13-feet-tall, will remain at Pace through October 24; a maquette for Jardin d’émail that was shown at Pace in 1969 will also be on view. “For Dubuffet, it was always about disruption,” Shultz added, referring to the enveloping and overwhelming qualities of the artist’s works. “Disrupting the normal circuits of your ability to perceive the world around you.”

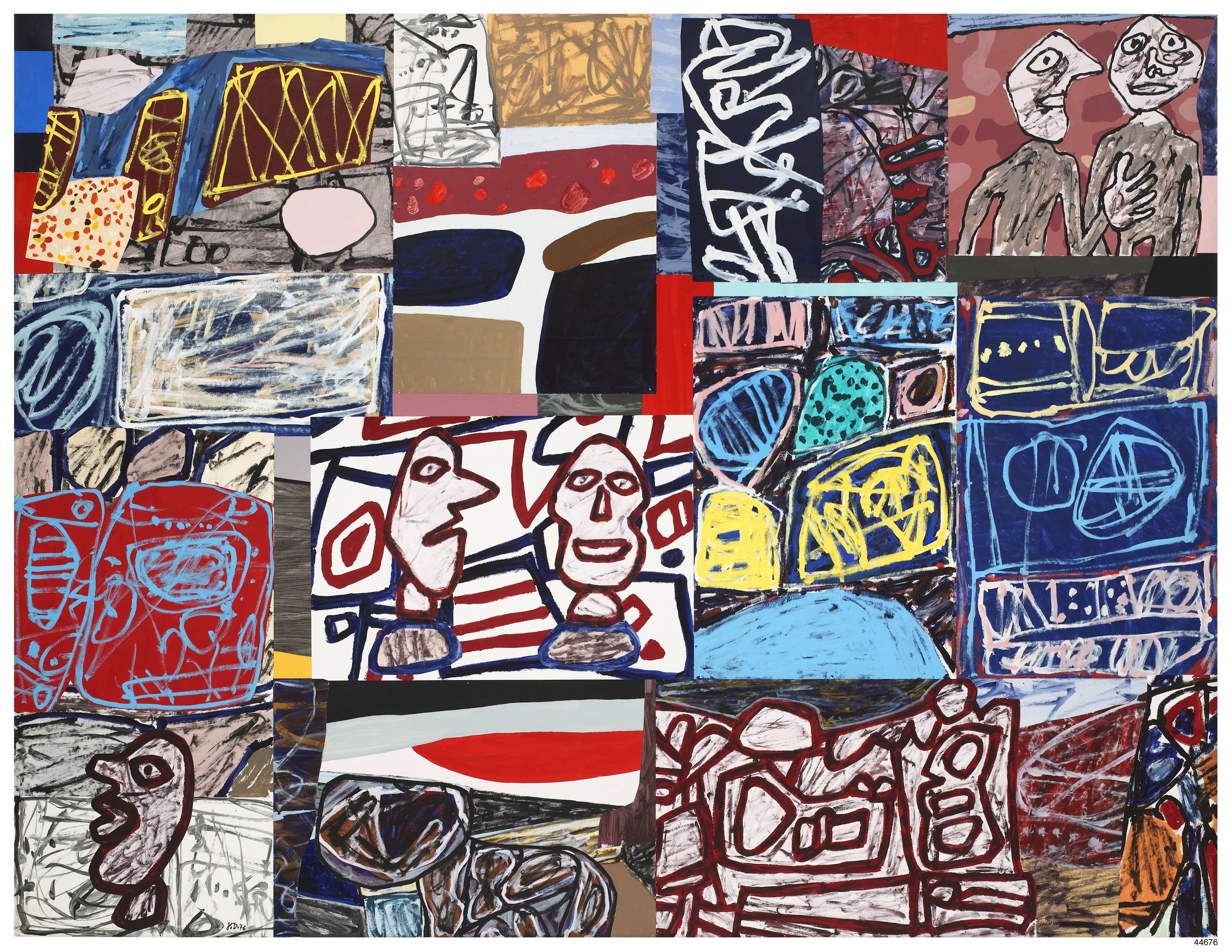

Jean Dubuffet, Fête villageoise, 1976, acrylic and collage on paper mounted on canvas.

© 2020 Jean Dubuffet/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Into the 1970s, the artist remained restlessly innovative.

Later years in Dubuffet’s career saw breakthroughs in works on paper and canvas. Fête villageoise (1976), an acrylic and collage on canvas work, features a frenetic patchwork of lines, shapes, and moon-faced figures, and Scène et site (1979), an acrylic piece on canvas-backed paper, is a dreamy vision of two figures floating against an entanglement of gray, blue, and red forms. The artist died of emphysema in Paris in 1985, but his work, which has fetched millions at auctions in recent years, has since been the subject of landmark retrospectives at the Centre Pompidou in 2001 and the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland in 2016. His pieces can be found in collections around the world, including those of the Pompidou, the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, the Museum Ludwig in Germany, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and MoMA in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. In 2021, the Barbican Centre in London will open an exhibition spanning four decades of Dubuffet’s practice.

Published at Thu, 03 Sep 2020 16:07:34 +0000