[ad_1]

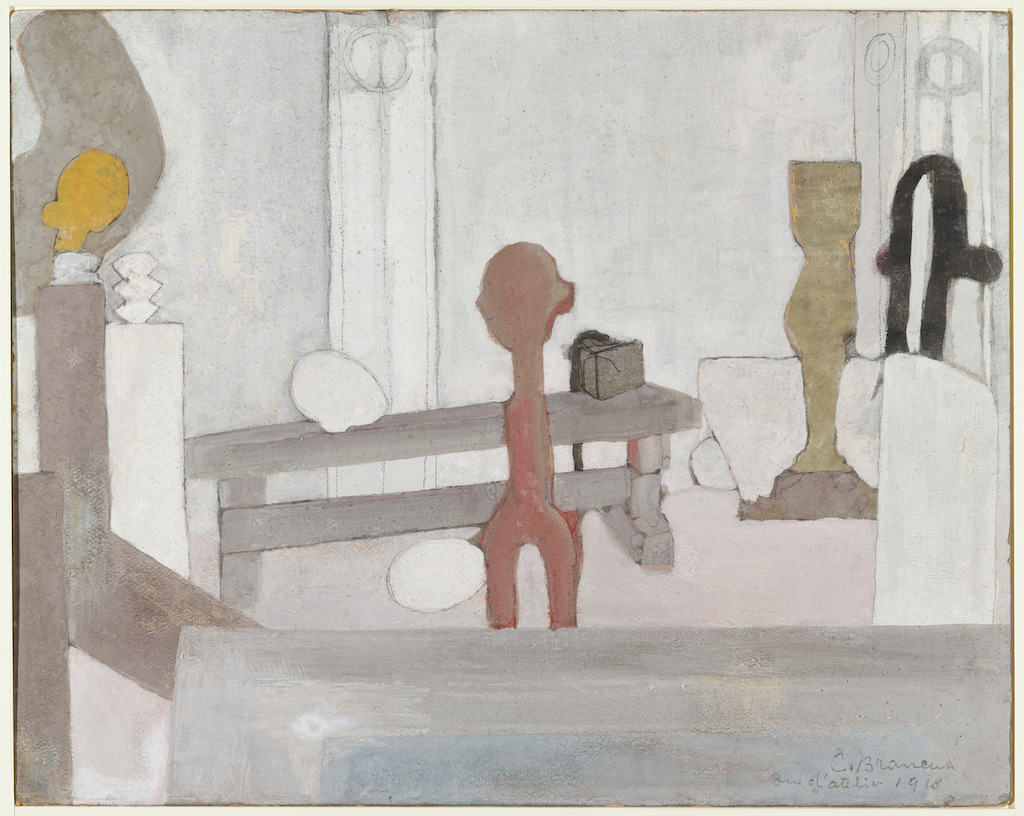

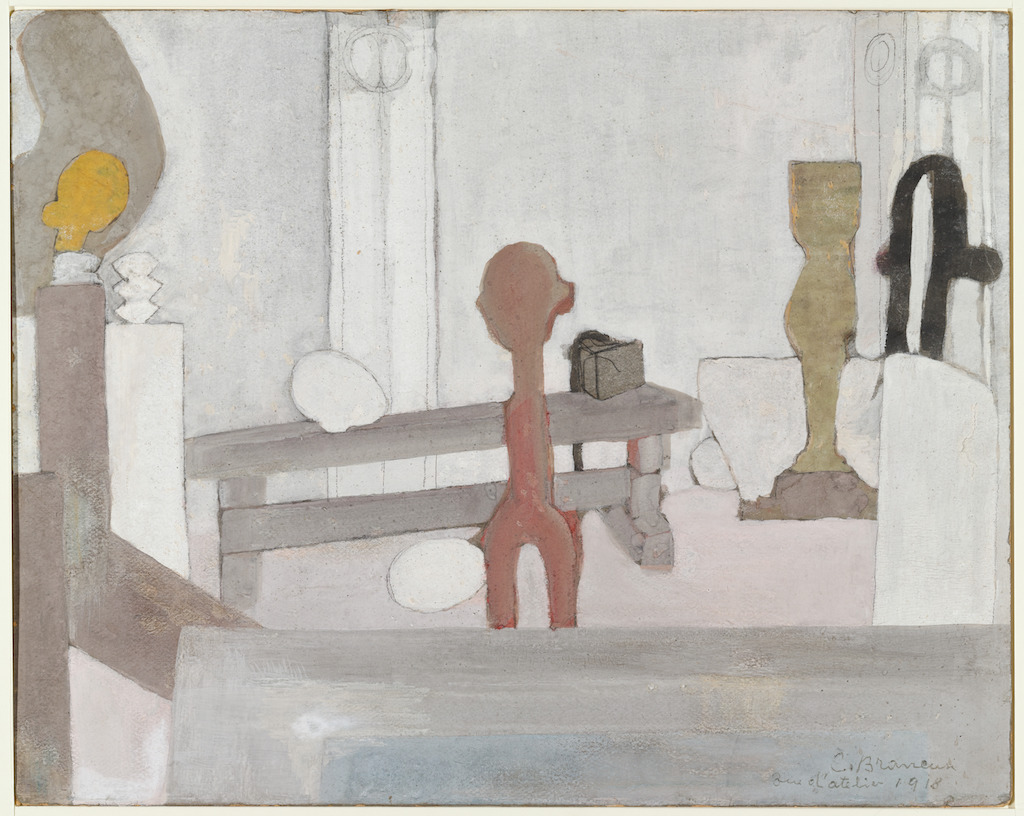

Constantin Brancusi, View of the Artist’s Studio, 1918, gouache and pencil on board.

©2018 ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK, AND ADAGP, PARIS/THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, THE JOHN AND LESTER AVNET COLLECTION

Few European artists in the first half of the 20th century worked in as minimal a mode as Constantin Brancusi, whose sculptures offered combinations of stripped-down materials that, in the artist’s eyes, resembled birds and mythical beings. Some of these works are on view now at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where an exhibition of Brancusi’s work contextualizes his three-dimensional objects with archival materials. Republished below in honor of the show is James Johnson Sweeney’s essay about Brancusi, “The Brancusi touch,” which first appeared in the November 1955 issue of ARTnews. Written on the occasion of a show of the artist’s work at the Guggenheim Museum, where Sweeney served as director, the essay focuses on the simplicity of Brancusi’s work, which Sweeney said shouldn’t be confused with a lack of imagination. The essay follows in full below. —Alex Greenberger

“The Brancusi touch”

By James Johnson Sweeney

November 1955

The importance of texture in Brancusi’s sculpture, exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum until January and then at the Philadelphia Museum, is illustrated with photographs taken by the artist in his studio

Brancusi’s sculpture is the art of a man born close to nature who has always remained close to nature. Far from being an occult expression as it has sometimes been regarded, Brancusi’s sculpture is the simple and direct expression of the material he employs. It is a nature poetry in sculpture in so much as it is an imaginative exploitation of the essential nature of the materials employed: a revelation through simplification and intensification of the inherent characteristics of those materials and at the same time a metaphorical manifestation or epiphany of them.

An ovoid stone balanced on its thin edge on a mirror in the depth of which it is reflected is never by Brancusi intended merely to resemble a fish: it is a stone, which swims—a stone fish. A marble form entitled Leda is not meant to look like a swan; it is a piece of marble that has certain characteristics of a swan, principally in the way its bulk seems to float on the surface of its base, as a swan floats almost clear of the water. Brancusi’s Eve is not a reminiscence of some African Negro carving; it is a black of elm, the structure of which nature has so organized that an artist with respect for its innate conformation had only to strip it imaginatively down to this to reveal a natural metaphor of the female form. His Adam is male in its sturdiness and the counterpoint of rhythms the artist has brought out in his angular cross cutting of the natural grain of the wood. An aspiring form in highly polished brass simulates no bird ever seen; but it is a form which through certain features of its material—the burning glow of its polished surface and its attenuated form—can be seen as the sun drenched flight of a bird through space. Another, a hunched shape in grey marble gives the impression of “the resting” of a bird rather than an actual bird form; and the plain, diagonally cut force of a small rounded mass of marble may suggest the open beaked hunger of a blind fledgling in Brancusi’s Oiselet.

Constantin Brancusi, Fish, 1930, blue-gray marble on three-part pedestal of one marble and two limestone cylinders.

©2018 ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK, AND ADAGP, PARIS/PHOTO: IMAGING AND VISUAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT, MUSEUM OF MODERN ART/ACQUIRED THROUGH THE LILLIE P. BLISS BEQUEST (BY EXCHANGE)

In his studio in the Impasse Ronsin are two sculptures: one entitled Walking Turtle; one, Flying Turtle. Walking Turtle is carved from a single block of wood, but is, unfortunately, badly worm-ravaged. Brancusi felt its condition was too delicate to risk transportation. He explained that once, with this possibility of deterioration in mind, he had thought of making another version in marble. But in studying the two materials he realized at once that the curved grain of the wood expressed the rounded movements of the walking animal—“how it clung to the earth”—in a way that the straight grain of the marble never would. The straight grain of the marble was only adaptable to the communication of a taut, outstretched movement—the tension of flying, as he saw it. So his marble version took that character—The Flying Turtle.

This is the poetry of material as Brancusi’s sculpture embodies it, the metaphorical revelation of the essential characteristics of the material employed. This is at once the simplicity and the imaginative subtlety of Brancusi’s art.

In his work nothing is indirect, nothing is occult. The material always speaks in its individual form and color. The artist never forces it, but always encourages it, draws it to some expression beyond itself through some simple, metaphorical reference.

Constantin Brancusi, Young Bird, 1928, bronze on a two-part pedestal of limestone and oak.

©2018 ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK, AND ADAGP, PARIS/THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, GIFT OF MR. AND MRS. WILLIAM A. M. BURDEN

Simplification and intensification are the keys to his vision: revelation by simplification rather than by complication.

A friend visiting New York recently from Melbourne, where Mademoiselle Pogany still lives, had assured me of the remarkable clarity of resemblance even today after four decades between that extremely simplified portrait and its model.

Some weeks again in trying to explain my own satisfaction the title, Prometheus, which Brancusi gave his starkly simplified marble head in the Arensberg Collection, I saw no evident link between it, the Fire-bringer or his eagle. On looking into a classical dictionary I found that his mother was Clymene the Oceanid. Immediately I felt I was on the track: here, a marble head, almost featureless, that of a child born in the sea, washed up in the shingle. But when I asked Brancusi he explained simply that it was the head of the suffering Prometheus. “If it is properly set you see how it falls over on his shoulder as the eagle devoured his liver.”

Maiastra was another mystery until Brancusi explained it was a bird in Rumanian fairy tale “that everyone in Rumania knows”—the classic story of a lover, seeking his princess, finally guided through the forest by the bird Maiastra to the place of her imprisonment.

In conversation Brancusi frequently refers to the saying of an Oriental sage to the effect that if one would be happy he should become as a young child. And the wonder of simple things which make a child’s world has never left Brancusi. He sees in the simple things of the world the soul of universal beauty.

A wooden cup on a carved wood column has the dignity of the ages. The peasant, the simple man of nature, the child, the artist with his religious love of what gives a material its character of individual beauty and the ability to isolate this and transform it through the imagination are what lies behind the richness of Brancusi’s simplicity.

If one may be forgiven a comparison with the product of another art expression, perhaps the closest analogy to Brancusi’s gifts is to be found in Blake’s Songs of Innocence:

Piping down the valleys wild

Piping songs of pleasant glee

On a cloud I saw a child

And he laughing said to me:

“Pipe a song about a Lamb!”

So I piped with merry cheer,

“Pipe, pipe that song again;”

So I piped; he wept to hear . . .

Here, too, the material is brought to its simplest and yet subtlest: a simplicity which is never poverty—a plain statement, but always the glow of imagination within it.

It has been said that “a work of art has in it no idea which is separable from the form.”

This is the essence of Brancusi: his impeccable fusion of material, shape and metaphor.

[ad_2]

Source link