[ad_1]

Although Jacob Lawrence is best known his groundbreaking “Migration of the Negro to the North During World War I” series, which is now partly on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he worked prolifically. This month, the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, is shining a light on Lawrence’s 1954–56 series “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” which its 30-panels are being reunited for the first time in 60 years and which will soon travel the nation. With that show in mind, below is a profile of Lawrence from a 1944 issue of ARTnews by Aline B. Louchheim. In it, Lawrence addresses his realist gaze—he always “tried to paint things as I see them.” The article follows in full below. Read Lawrence expert Leslie King-Hammond’s commentary on the profile here. —Alex Greenberger

“Lawrence: Quiet Spokesman”

By Aline B. Louchheim

October 15–31, 1944

The paradox that the most effective propaganda for understanding the Negro problem should be visual truth is the essence of Jacob Lawrence’s work. For this young Negro has, in his own words, “tried to paint things as I see them.” In this lies his power as a painter; his perception and his comprehension are never literary, and his mode of expression is pictorial rather than illustrative. Lawrence’s pride (certainly merited) is the fact that his work has reached a wide public through acceptance of museums across the country, a tribute to a painter with a purpose rather than a propagandist.

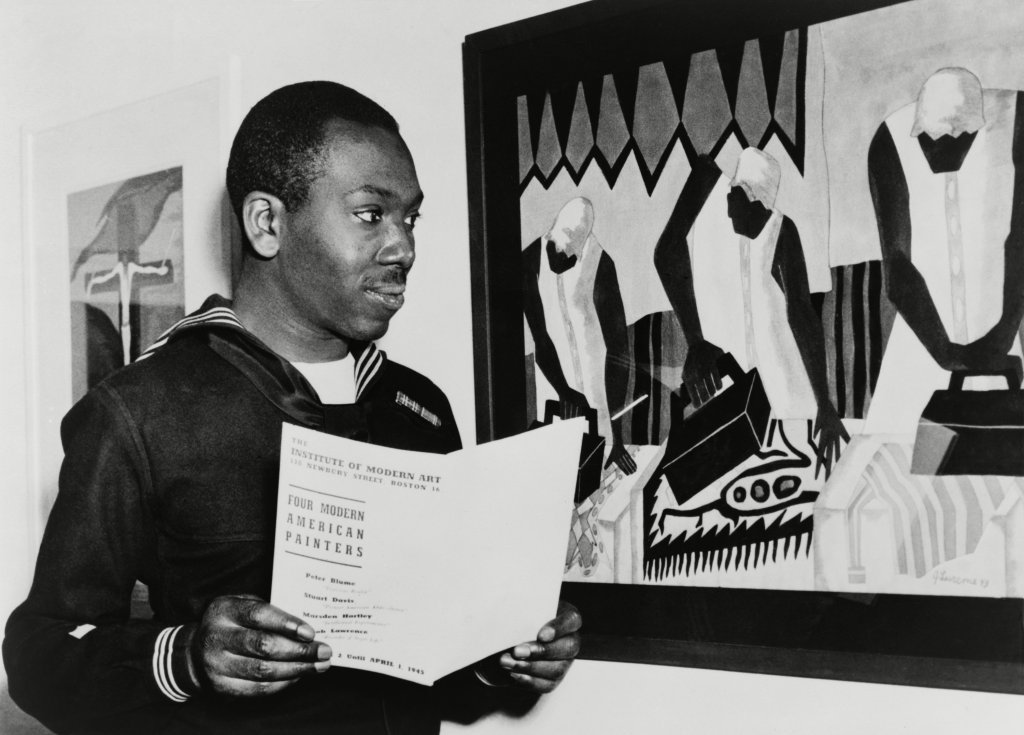

Assigned to “Station Museum of Modern Art” by the Coast Guard for the opening of his one man show, he looked at his gouaches, some of which he had never seen hung before, with modest pleasure. The forthright paintings, devoid of bitterness or overstatement, are reflections of the sincerity and honesty of the man.

The way Lawrence sees is in terms of pattern in bright primary color, unmodulated (so that no black and white reproduction can do him justice), and in simplification of form. Form is simplified in order to articulate the essentials. Detail is suppressed except where it functions both as part of design and basic part of fact. His steep perspective generates immediacy.

Lawrence seems to have been born with a sense of pattern. “I always used to make designs as a kid,” he says. “Used to make masks, and designs for rugs—for anything. And I’ve always been interested in stage designs. I’ve even made some theater models.” To design state-sets is one of his post-war hopes, along with a Guggenheim, a trip to Mexico, a series of paintings on John Henry, and a try at silk-screens.

Born in Atlantic City, his mother brought him as a child to Harlem via Philadelphia. His first break, he thinks, was that his work “as a kid” came to the attention of Charles Alston, the Negro painter, who was then studying at Columbia. Alston urged him to come to the 135th Street Public Library classes. He continued studying with Alston and Henry Bannarn. The Federal Arts Project and beginning in 1941 a Rosenwald Fellowship three years running gave him his next opportunities.

Lawrence has painted Negro themes always, from historical series to contemporary life, which he considers “all part of the same problem, and its progress.” His honeymoon to New Orleans in 1941 was his first trip South, where Jim Crowism and the desperate economic plight of the Negroes became an emotional reality. “It didn’t surprise me,” he says, “but for the first time I really felt it.” On Coast Guard duty in the South later he started pen and ink drawings. “Maybe because of the way they think, Southerners look different—cold, inhuman,” he added, indicative of the man who feels through his eyes.

The Migration of the Negro to the North During World War I comes from the honeymoon year. Reproduced in color by Fortune, and on two year tour of the country, this series, owned half by the Phillips Memorial Gallery and half by the Museum of Modern Art, is now on view in its entirety. The sixty panels tell a story strangely contemporary to World War II. These are facts made moving and alive, through understatement. The reasons for leaving the South, the hopes, the disillusionments unfold. Typical of Lawrence’s sense of justice, rather than subservient acceptance or cynical revolt, are the final panels which show, despite its heartrending disappointments, the few advantages of the North—the right to vote and a chance to educate one’s children. The simple dignity of the running prose captions have as unadorned an impact in their quiet truth as the paintings. “My wife helped with those,” he explains.

In 1943 Lawrence produced a vividly colored, splendidly designed series on Harlem, ranging from scenes of squalor to those of swing. Vogue published some of these in color. In a different vein are the series on lives of great Negro heroes and leaders—Toussaint L’Ouverture, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, John Brown—done between 1937 and 1942, with a subdued palette, calmness, and less abstract form simplification.

In October, 1943, Lawrence enlisted in the Coast Guard, where he has found, in spite of racial rank, the greatest democracy he has known to date. Much of this is due to the understanding and encouragement of Lt. Comdr. Carlton Skinner, Captain of the U.S.S. Sea Cloud, where Lawrence served as Steward’s Mate. Mr. Skinner reduced the artist’s table-waiting duties to a minimum and was instrumental in having him transferred to his present duty with Public Relations. He painted Mr. Skinner—a genre surprising for him. The new Coast Guard scenes at the Museum reflect optimism and happiness. Aside from subject-matter, where white and Negro crew members work and relax together, there is even more brilliant primary color and a new maturity in the largeness and freedom of design. The uniforms, the ship, semaphore flags, checker-games appear in vivid blues, vibrating yellows, bright, clear reds. In the small world of the ship, with common danger to be faced—(“We had our first contact the second night out and we were all forgotten”)—racial prejudices are forgotten.

Lawrence’s favorite of the Coast Guard group is also the most interesting. It is called Prayer, and for the first is a completely subjective painting. In the mysterious blues of the ship’s interior, a figure has flung himself to his knees in prayer against the lower bunk. Lawrence has created a vastness, not only of the sea, but of the universe, and in the solitary figure in his moment of intense privacy, he has captured the loneliness of the ship on the sea and of man seeking contact with God. The painting is perhaps a presage of the future, when deeply felt personal emotional with fuse with the lucid visual patterns of fact.

[ad_2]

Source link