[ad_1]

“Humbert Humbert tried hard to be good,” the protagonist of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita attests, referring to himself in the third person. ”Really and truly, he did.”

By the end of Nabokov’s 69 chapters, enunciated with dulcet prose, dark wit and no conflicting testimony, the reader almost believes him. It’s the ultimate testament to Nabokov’s mastery that so many readers find themselves sympathizing with a middle-aged man who kidnapped and routinely raped a 12-year-old girl ― and gets away with it.

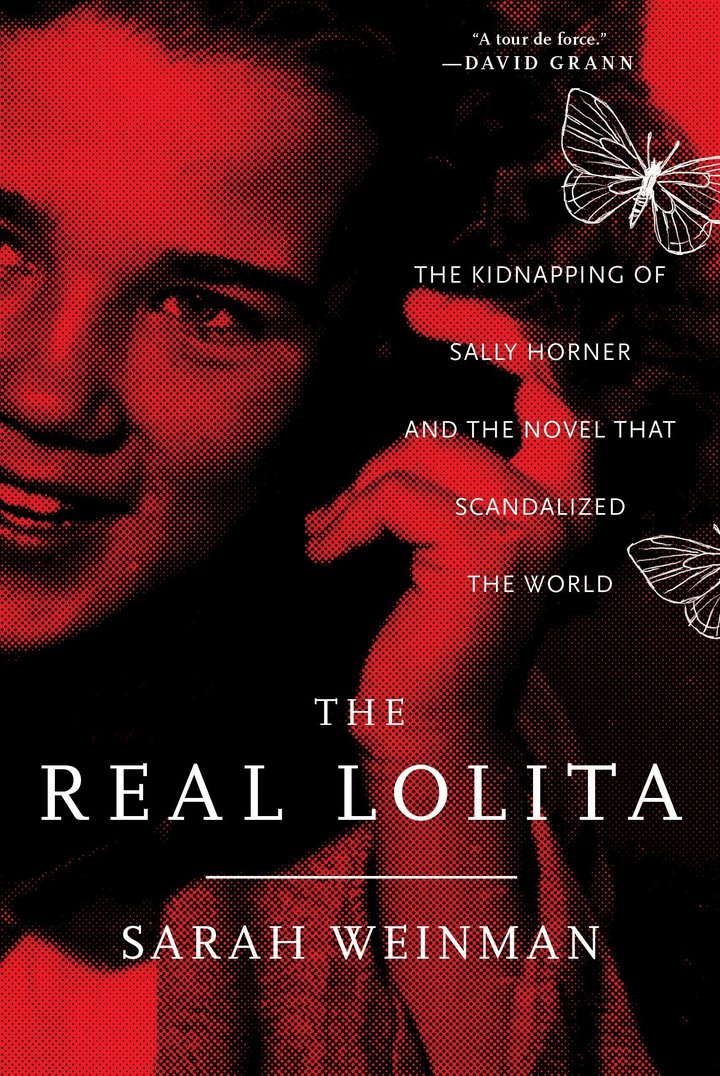

As Sarah Weinman writes in her new work of nonfiction, The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel that Scandalized the World, “The appreciation of art can make a sucker out of those who forget the darkness of real life.”

Weinman’s book, which hit shelves physical and digital on Tuesday, makes a sturdy case that Nabokov’s tale ― the one he claimed in interviews after its 1955 publication was pure fiction ― was in fact inspired by true events involving a real child named Sally Horner.

When he was alive, Nabokov infamously refuted critics’ attempts to link Humbert’s abhorrent quest to “fix once and for all the perilous magic of nymphets” to actual events. What’s more, he insulted any “ferrety, human-interest fiend, the jolly vulgarian” who would dare ask.

More than 40 years after his death, Weinman is that vulgarian.

Amazon

The Real Lolita introduces readers to Horner, an 11-year-old schoolgirl who lived in Camden, New Jersey. In 1948, she was approached by Frank La Salle, a convicted child molester freshly released on parole, at a five-and-dime store. After spotting Horner steal a five-cent notebook on a dare, La Salle passed himself off as an FBI agent and threatened to have Horner arrested if she didn’t follow his every instruction. Horner did as he said.

According to Weinman, La Salle held Horner in captivity for almost two years thereafter, posing as her father by day and raping her by night, as they moved cross-country from Atlantic City to Baltimore to Dallas to San Jose, California. Horner finally escaped when a neighbor suspected the “family” relationship was fishy and called the cops. Upon being rescued, Horner was shunned by her classmates for the sexual activity forced upon her, smeared as a “slut” and a “total whore,” according to her sole school friend Carol Starts.

At 15 years old, Horner and Starts skipped town for a weekend getaway, taking the bus to Wildwood, New Jersey. Horner met a boy there, who was driving her around in his car in the early morning of Aug. 18, 1952, when he smashed into a parked truck. Horner was killed instantly.

Horner’s kidnapping and death were covered by news outlets at the time. But little attention was given to the individual behind such a tragic fate. Horner’s name vanished from public consciousness long before that of literature’s prized nymphet entered into it.

The Real Lolita expands upon Weinman’s longform reporting, published four years ago in Hazlitt, which painstakingly pieces together the story of Horner’s brief and harrowing life. The author visited the places Horner lived and interviewed the people who knew her to create an engrossing narrative, occasionally consulting her own imagination to fill in the blanks left by questions unanswerable.

Sally Horner’s name vanished from public consciousness long before that of literature’s prized nymphet entered into it.

Horner’s tale is interspersed with a chronological account of Nabokov’s process writing Lolita from start to finish. Along the way, she reveals evidence of Horner’s influence on his work, such as a notecard handwritten by Nabokov that directly references Horner’s abduction by a “middle-aged morals offender.” The parallels between Nabokov’s text and Horner’s life range from subtle to obvious.

Most glaring is when Humbert asks himself if he had “done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, fifty-year-old mechanic, did to eleven-year-old Sally Horner?” However, throughout her extensive interviews with ardent fans and critics of Lolita alike, Weinman found none among them recalled the line.

Throughout the book, Weinman makes a careful distinction between Horner and contemporary victims of abuse and trauma ― like Elizabeth Smart and Jaycee Duggard, who published books recounting the horrors they lived through. They “were able to tell their stories the way they wished and when they chose,” as Weinman writes. “In doing so, they sought to make something meaningful of their lives.”

But the pain, complexities and humanity of Horner’s story were snatched from her the moment she became a fictional sylph ― as Humbert put it, “the little deadly demon among the wholesome children” ― not so much a person as an object of obsession. (For proof, look no further than SparkNotes’ description of Lolita as an “underage sexpot.”) Instead of Horner’s own account of surviving a predator, “we have the word of Humbert Humbert,” Weinman wrote in Hazlitt, “whose charm and erudition allows the reader to forget — briefly for some, completely for others — that he is a monster.”

Weinman’s book includes a disturbing example of a publisher relaying his hopes to Nabokov that Lolita “might lead to a change in social attitudes toward the kind of love described in Lolita, provided of course that it has this authenticity, this burning and irrepressible ardor.”

Is that the lesson to be learned of Sally Horner’s life story?

HECTOR RETAMAL via Getty Images

In writing Lolita, Nabokov inducted Horner into a long line of women and girls whose value as people is eclipsed by their role as “muse” or “inspiration” to an acclaimed male artist.

Earlier this year, a 1905 painting by Pablo Picasso, titled “Fillette à la corbeille fleurie,” sold for $115 million at auction. It depicts a nude prepubescent girl who, despite the fact that art historians have rigorously researched the painting itself, experts know little about, save for the fact that Picasso called her Linda and she probably “died sadly young.”

Linda occupies the same ghostly status of being “known and nameless” as Horner; a pretty picture, a compelling character, only remembered through the distorted lenses of a powerful man.

Me Too revelations have, in part, prompted a reevaluation of this cultural condition, in which women’s lives serve as disposable nuggets of artistic inspiration off of which men profit. As a result, some dissenters, fearing for the fates of iconic artworks forged of this mold, have advised against ransacking our archives and holding old works up to “today’s standards.”

But Weinman’s book doesn’t excoriate Nabokov’s text or demand it be scrubbed from the cannon forevermore. Instead, she contextualizes his classic through an alternate telling of events, in which Horner is subject and not object.

“Knowing about Sally Horner does not diminish Lolita’s brilliance, or Nabokov’s audacious inventiveness,” Weinman writes in her introduction. “But it does augment the horror he also captured in the novel.”

The Real Lolita is a revelation, not simply because of what it reveals about Lolita’s dark roots, but for the course of action it proposes. We don’t have to “cancel” every problematic work of art gifted to us by a male genius on high, but we can devote resources and attention to the lives sapped of their humanity for the cause.

CORRECTION: An earlier version misstated the first name of the novel’s Lolita, Dolores Haze, as Florence.

[ad_2]

Source link