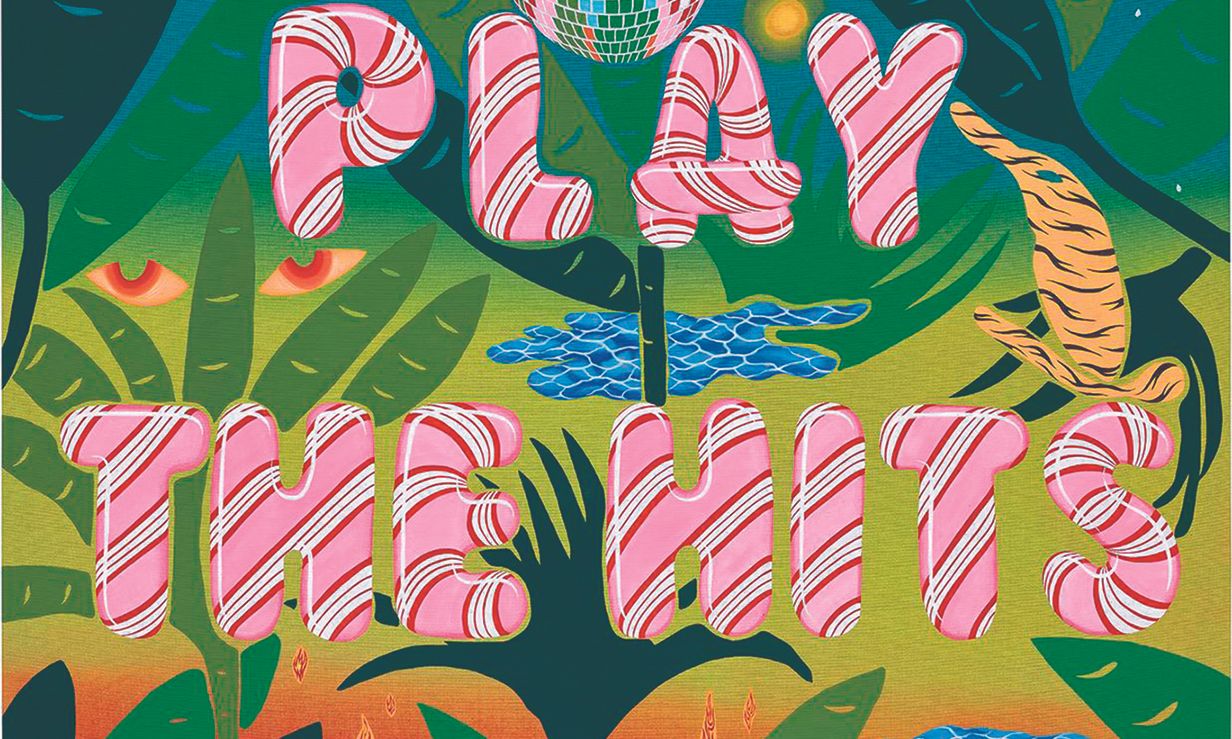

Hot ticket: Untitled (Play the Hits) (2021) by Joel Mesler, who turned from dealing art to making it, sold for £533,000—more than three times its low estimate—last month

© Joel Mesler

Blue-chip investments. Repeat sale price indices. Rates of return. Securitised funds. Commodification. Fractionalisation.

The argot of art as an alternative asset class is well established, if not its track record as a reliable way of making money. But are we reaching a point where this way of thinking, like art history, has finally become bunk?

Earlier this month, various media outlets reported that art was the top-performing “investment of passion” in 2022, with annual returns rising to 29%, according to the Knight Frank Luxury Investment Index (KFLII).

Successful auctions of several prestigious single-owner collections, such as those amassed by Paul Allen and Anne Bass, were the key. “With the provenance of a high-profile collector attached, blue-chip works routinely break auction records, and last year was no exception, with five achieving over $100m,” says Sebastian Duthy of Art Market Research, which provides the data for the KFLII.

It appears that the only way is up for blockbuster single-owner auctions, which, in terms of volume, represent a tiny fraction of the resale art trade. What about the rest of the auction market? How is that faring as an asset class?

London’s recent marquee series of Modern and contemporary auctions at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips showed how difficult it has become to treat art like a commodity that can be reliably tracked on a Bloomberg trading screen.

Young, NextGen, red-chip art—call it what you will—has turned into a problematic disruptor. Works by the latest crop of hard-to-source names of the moment routinely sold for multiples of their estimates (and gallery prices) at all three auction houses, are seemingly sucking demand out of the market for works by art history’s supposed blue-chip brands.

At Phillips’s evening sale on 2 March, for instance, Untitled (Play the Hits), a big greetings card-style painting from 2021 by the American gallerist-turned-artist Joel Mesler, sold for £533,400 against a low estimate of £150,000. Mesler is currently the subject of a solo show at the private Long Museum, West Bund, Shanghai (until 18 April). A few lots later, Howard Hodgkin’s 2002-13 oil painting, Summer Rain, long validated by museums, sold for £292,100 against a low estimate of £500,000.

General conclusions should not be drawn from isolated results, but time and again at all three of the houses’ evening sales there would be multiple six-figure bids for works by young artists who feature in recent, current or future shows at taste-making galleries. The record £730,800 given at Christie’s for a 2021 abstract by Michaela Yearwood-Dan (included in the group show, Rites of Passage, at Gagosian, London, until 29 April) and the £927,100, also a record, paid by Gagosian at Phillips for the 2014 pool painting, Threshold, by Caroline Walker (recently featured at Adrian Cheng’s K11 foundation in Shanghai) were other cases in point.

Coaxing millions out of bidders for works by old or dead artists represented in renowned museums proved a tougher ask. Kandinsky’s restituted 1910 proto-abstract landscape, Murnau with Church II, was the out-and-out Modernist masterpiece of the week, but Sotheby’s sold it for a single bid of £37.2m, albeit a record for the artist at auction. The market for German Expressionism, one of the most influential movements in 20th-century art, seemed on the point of collapse at Christie’s, where paintings by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel and Max Beckmann estimated in the £600,000-£2.4m range all failed to sell.

Kandinsky’s Murnau with Church II (1910), the subject of a long restitution battle, sold for a single bid at Sotheby’s last month

Photo: Sotheby’s

“There’s been a generational shift in Germany. Collectors in their 40s now collect contemporary art,” says Hugo Nathan, a co-founder of the London-based art advisers, Beaumont Nathan. Explaining the appeal of young art over museum-validated Modern masters, Nathan adds, “You can bid £400,000 and be applauded. It’s a lot more fun than spending a couple of million on a Modern work that no one notices. The market is now all about trophies and new art, and there’s not a lot in between”.

Given that the new paintings by George Condo that in February inaugurated Hauser & Wirth’s latest gallery, in West Hollywood, were priced up to $3.5m each, there is a sort of financial logic behind someone betting big, six-figure sums on works by young, upwardly mobile artists. And when auction prices for one set of catnip names begin to peak, the auction houses simply introduce another. This time round in London, out went Anna Weyant and Jadé Fadojutimi (both now represented by Gagosian), and in came Joel Mesler, Michaela Yearwood-Dan and Caroline Walker.

The fragmentation of the market into young art, trophies and the rest, which the latest London auctions seemed to underline, also reflects seismic, non-financial forces at play.

According to Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity, a ground-breaking study by the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa, published in 2013, the pace of technological change has made our sense of time seem to flow ever faster, resulting in what Rosa identifies as a “shrinking of the present”. Unable to cope with the accelerated tempo of life, our brains concentrate more than ever on the now (as Sotheby’s has titled its latest format of contemporary art sale).

This is a very different situation from that which prevailed in 1899 when Thorstein Veblen published his classic sociological study, The Theory of the Leisure Class. In those days America’s new money felt insecure about its social status, leading the Robber Barons to pay huge sums for 18th-century English aristocratic portraits. Now “cool” has usurped class as America’s predominant status symbol, say Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter in their 2006 book, The Rebel Sell: How the Counterculture Became Consumer Culture. Today’s plutocrats covet Banksy and Basquiat, not Gainsborough and Reynolds, and buying cool, young art keeps them feeling young. In addition, as several contemporary sociologists have pointed out by way of updating Veblen, experiences are increasingly replacing possessions as signifiers of status.

But looking at the recently published seventh edition of The BMW Art Guide with its entries on 304 private collections of contemporary art across the world, are those pages not filled with very expensive possessions? That’s true, yet all those concrete-floored white cubes filled with new and newish art are also the residue of the international collector lifestyle, of what sociologists now identify as the “consumption experience”.

Flying round the world to art fairs, auctions, biennials and gallery openings has become a distinct lifestyle experience for the relatively small group of ultra-wealthy individuals who keep the contemporary art world humming.

“Essentially, it’s hand-holding,” says the seasoned London-based contemporary art dealer Niru Ratnam, describing the concierge services required to keep international collectors engaged with a gallery and its artists. “[The collectors] tend to be a bit on the older side and like being told there’s a nice dinner. There is also hand-holding to keep them in a gallery’s orbit,” says Ratnam, recalling a 2019 Frieze party at which nine gallerists competed with each other to sit next to “their” collector.

So where does that leave those very expensive trophies, such as Kandinsky’s Murnau with Church II? Many in Sotheby’s auction room were baffled that such a historically important painting should fall to just one £37.2m bid from its third-party guarantor, widely rumoured to be Sotheby’s owner, Patrick Drahi. Why was there not more competition? Why was this not an “investment of passion” for another of the world’s population of more than 2,500 billionaires?

“It was just too expensive,” explains Guy Jennings, the senior director of The Fine Art Group advisory service. “It’s down to the number. If the estimate is too high, they don’t want to bid,” he says, referring to how the cut-throat competition between Sotheby’s and Christie’s has pushed the valuation of unique trophy lots to off-putting levels, even for the super-rich. At the Christie’s Paul Allen sale, star lots such as Cézanne’s La Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1888-90) and Lucian Freud’s masterpiece, Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau) (1981-83), also sold to single bids.

For Jennings, collectors’ focus on young art makes financial sense. “The money follows supply,” he adds. “There are plenty of artists and there’s plenty of trading going on. But who knows if these artists will be of interest in ten years’ time.”

Right. So there you have the current state of the art as an alternative asset class. The famous-name trophies are overpriced. So too, probably, are most of the works by those must-have young names. And it’s getting more difficult to sell the stuff in between.

But what price can you put on the lifestyle?