[ad_1]

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfamaian.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND THE THIRD LINE, DUBAI

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, whose sculptures, paintings, and drawings tend toward intricate geometric abstractions that confuse the eye and occupy the mind, has died at 97, according to ArtAsiaPacific, which first reported the news in English.

Farmanfamaian’s synthesis of modernist abstraction and local styles made her one of the most notable contemporary artists to come out of Iran. But it wasn’t until the past few years, following a traveling survey exhibition and a feature-length documentary about her career, that she received widespread acclaim in the international art world.

Critics, historians, and curators have ascribed a number of influences to Farmanfarmaian’s work, including Sufism, Iranian politics, and mosque architecture. While acknowledging that some of these had inspired her, she often reminded viewers that her work wasn’t intended to be particularly philosophical. Speaking of her abstractionist impulse in the 2014 documentary Monir, she said that, early on, “I wasn’t even aware I was working with geometric forms.”

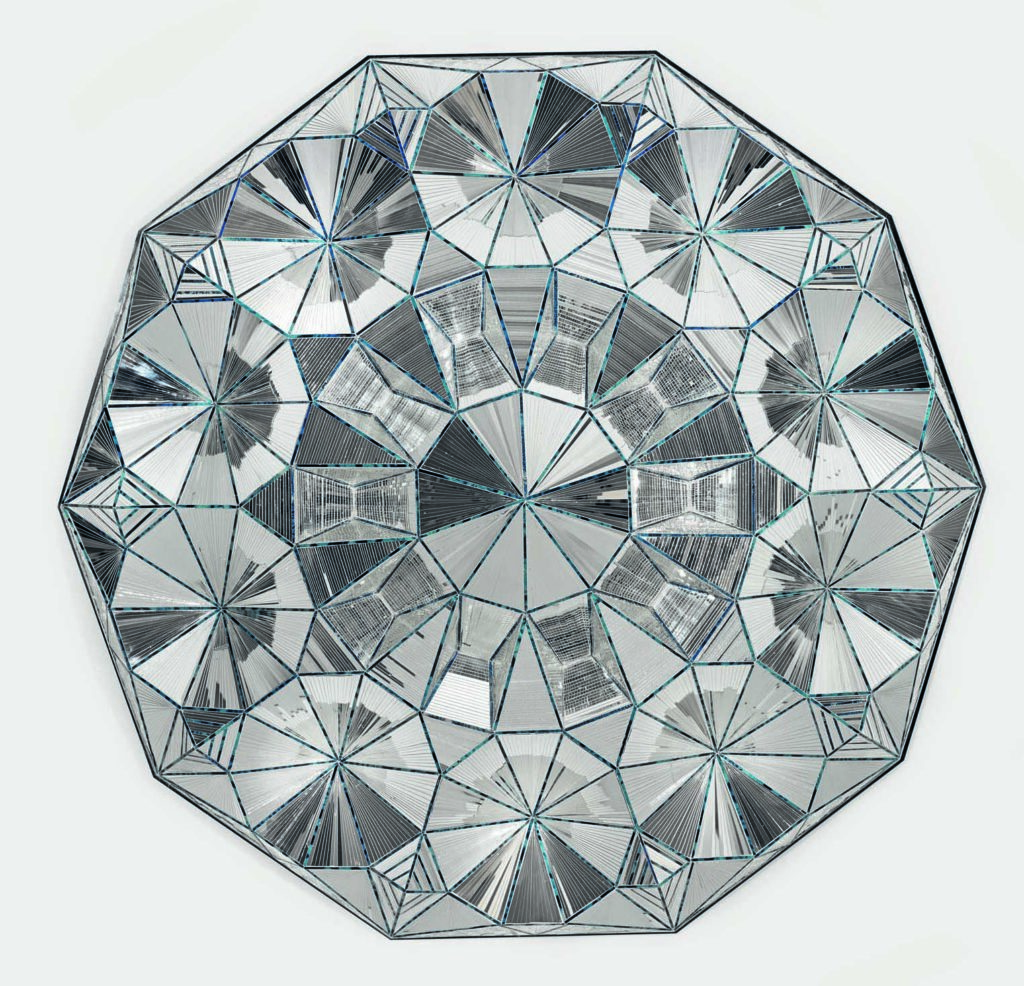

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Decagon (Third Family), 2011.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND THE THIRD LINE, DUBAI

Throughout her six-decade-long career, Farmanfarmaian created dazzling pieces featuring geometric planes that intersect, making for mindbending perceptual plays. In an interview with the Guardian in 2011, Farmanfarmaian explained that she first began using mirrors in her work during the early 1970s, after visiting the Shah Charegh mosque in Shiraz, Iran, and seeing mosaics there that reflect and distort visitors’ images. “It was so beautiful, so magnificent,” she said. “I was crying like a baby.”

The works she produced in the decades since were constructed from unevenly laid panes of glass, their surfaces reflecting light and the surrounding exhibition spaces around them. Frequently arranged into interlocking forms, they appear to shift as viewers move. Some works were painted, and when placed under light, they appear to fling specks of color out into the galleries in which they are exhibited. “Geometry has many different possibilities to create unlimited designs,” Farmanfarmaian told curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2014 in Interview magazine.

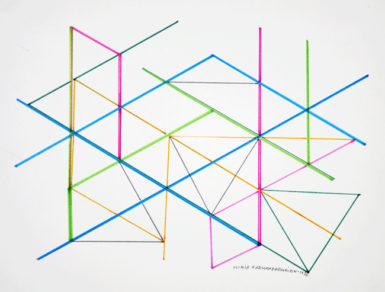

Farmanfarmaian’s work sometimes took on a more conceptual bent. In 1978 she created drawings using honeybees by laying out a piece of paper and ink along with honey and dates that she used to lure the insects. The resulting works on paper act as evidence of the bees’ paths across a given space—permanent records of something that would otherwise have been transitory.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Variation on a Hexagon 1, 1976.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND THE THIRD LINE, DUBAI

Farmanfarmaian was born in 1922 in Qazvin, Iran. In 1944, having studied at the University of Tehran, she moved to New York, where she took up work as a fashion illustrator. Relocating to the city allowed her to link up with some of the day’s most important artists, including John Cage, Louise Nevelson, and Joan Mitchell. While working on commission for the department store Bonwit Teller, she also became friendly with Andy Warhol.

In 1957, Farmanfarmaian married the artist Abolbashar Farmanfarmaian, and she briefly moved back to Tehran. The year after, she participated in the first edition of the Tehran Biennial, along with some of the most revered Iranian artists of the time, including Parviz Tanavoli and Marcos Grigorian (who organized the exhibition that year). She also showed at the Venice Biennale, where she represented Iran and earned a medal for her participation. She went on to appear in the 1964 edition of the Biennale as well.

Starting in 1979, however, Farmanfarmaian was unable to travel back to her home country. A revolution was taking place in Iran, and she and her husband were denounced as friends of the Shah, a U.S.-backed Islamic monarch who was ousted that year. She was exiled from the country and remained in New York until 1992, when she was allowed to return. (During her exile, her collection of folk art, which was housed in Iran, was destroyed.) She remained in Tehran through the end of her career.

A survey of Farmanfamaian’s work was mounted at the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Porto, Portugal, in 2015 and traveled to the Guggenheim Museum in New York that same year. Late-career notoriety earned her a place on the 2015 edition of BBC’s “100 Women” list. A solo exhibition of her work is slated to open at the Sharjah Art Foundation in the United Arab Emirates later this year.

In 2017 a museum devoted to her work opened in Iran, under the management of the University of Tehran. “It is a museum she has always dreamed of, where everyone could come to see her works, in her beloved Iran,” Sunny Rahbar, the cofounder of the Third Line gallery in Dubai, which represents Farmnfarmaian, told Harper’s Bazaar Arabia at the time of the opening.. “Another one of her dreams has come true.”

[ad_2]

Source link