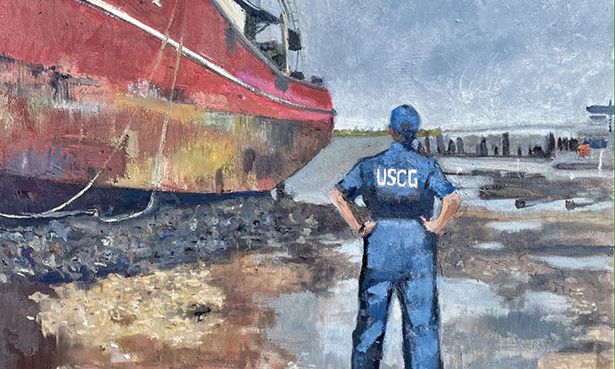

Amy DiGi’s painting Safety Hazard (2022) and another depicting the coast guard intervention after Hurricane Ida hit the US East Coast featured in a recent exhibition in New York of works from the coast guard collection Courtesy of the artist

When the US military evaluates its assets, it tallies its fighter jets, attack helicopters, anti-tank missiles, naval destroyers, grenade launchers, trained personnel and anything else a combat force might need. A perhaps lesser-known asset in the military’s arsenal is its series of art collections, holding tens of thousands of works.

The primary purpose of these art collections is to inform the public about what the US military does. Joan Thomas, the art curator for the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Quantico, Virginia, says: “Our collection is about the human experience and when people are thrust into a very difficult situation.” At a time of war in Eastern Europe and when so much entertainment glorifies combat, the tone of the marines’ art collection is not “hurrah, aren’t we great”, Thomas says, but a “truthful portrayal of what someone has experienced”.

Some images in the army’s art collection are “more macho”, says Sarah Forgey, its chief curator, while “some are actually anti-war, questioning the wisdom of what they are doing”. There have been fewer of the latter style of works, she adds, since the army became an all-volunteer force.

Each of the five branches of the US military (the air force, army, coast guard, marines and navy) has its own collection, curator and exhibition schedule. Most of the works in these collections do not show violence. In battle, Thomas says, “combat artists are expected to fight first” and then sketch what they see. Many works depict enlisted soldiers’ day-to-day routines. A painting in the army’s collection by Martin Cervantez, for instance, depicts a sentry wearing a poncho in a downpour and urinating into a PVC pipe, “which is how you’re supposed to do it when you are in a forward position”, Forgey says.

Most of what soldiers do is something other than actual fighting. For instance, two recent paintings, Oil Spill and Safety Hazard by Amy DiGi—an artist in Yorktown Heights, New York—portray the coast guard responding to a damaged oil tanker that ran aground last autumn during Hurricane Ida. Both were included in a recent exhibition of new additions to the coast guard’s collection at New York’s Salmagundi Club.

The coast guard makes a greater effort than other US military branches to display its holdings, which have grown to more than 2,000 pieces in the 41 years since the programme launched. The Marine Corps, which has collected more than 11,000 works since 1942, displays pieces in a room at the National Museum of the Marine Corps. The army’s 35,000-piece collection, begun during the First World War, is almost entirely in storage at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The US Air Force Art Program, started in 1950 and numbering around 9,300 pieces, is accessible primarily through the air force website.

Civilian artists and active-duty soldiers often hear about the military’s interest in art through word of mouth. Don Borie, a retired graphic designer in Ocala, Florida, learned of the coast guard’s art programme from a fellow exhibitor at a local art show. Borie says he contacted the programme’s coordinator, who shared a list of the sought-after themes at the time. “I chose ‘combating piracy abroad’ and submitted the painting Somali Shakedown,” he says, which depicts the coast guard intercepting pirates (it is now in the coast guard’s collection).

The US army and navy’s collections are the largest and the oldest, containing drawings and paintings by enlisted soldiers and draftees that span more than a century. James Pollock, a painter in Pierre, South Dakota, was drafted into the army in 1966 and served for a time as a combat artist in the US Army Vietnam Combat Artist Program. The programme sent teams of soldier-artists into Vietnam between 1960 and 1970 to record their experiences, rotating them in and out after 135 days (60 in Vietnam and another 75 in Hawaii to create finished works).

Pollock submitted hundreds of works to the army’s collection, almost all of which represent soldiers’ mundane activities rather than combat scenes. “I tried to create work that related to what I actually experienced,” he says.

The military art collections’ curators have no budget to purchase works, so each new acquisition is donated by an active duty service member, veteran or interested individual. DiGi never served in the military, but her husband is an army veteran. In 2011 she applied to the coast guard for a five-day embedded artist deployment and was sent the following year to a boot camp in Cape May, New Jersey. There she watched a group of new recruits in training, producing around 30 sketches, several of which she developed into paintings back at her home studio and gave to the coast guard collection.

All branches of the military allow civilian artists to apply for short-term unpaid stints with military units, with the only requirement that the artists donate resulting pieces to that branch’s art collection. Some branches also have combat artists who go out in the field or on ships for longer periods. “They are civilians and are treated like embedded journalists, but they are paid by the navy,” says Gail Munro, the head curator at the Navy Art Collection, which comprises more than 20,000 works.

Portions of this collection, she adds, tour as travelling exhibitions to state and county museums around the country. “There are usually three exhibitions out at any time,” she says. Otherwise, the works often hang in high-level military offices, including at the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia.