[ad_1]

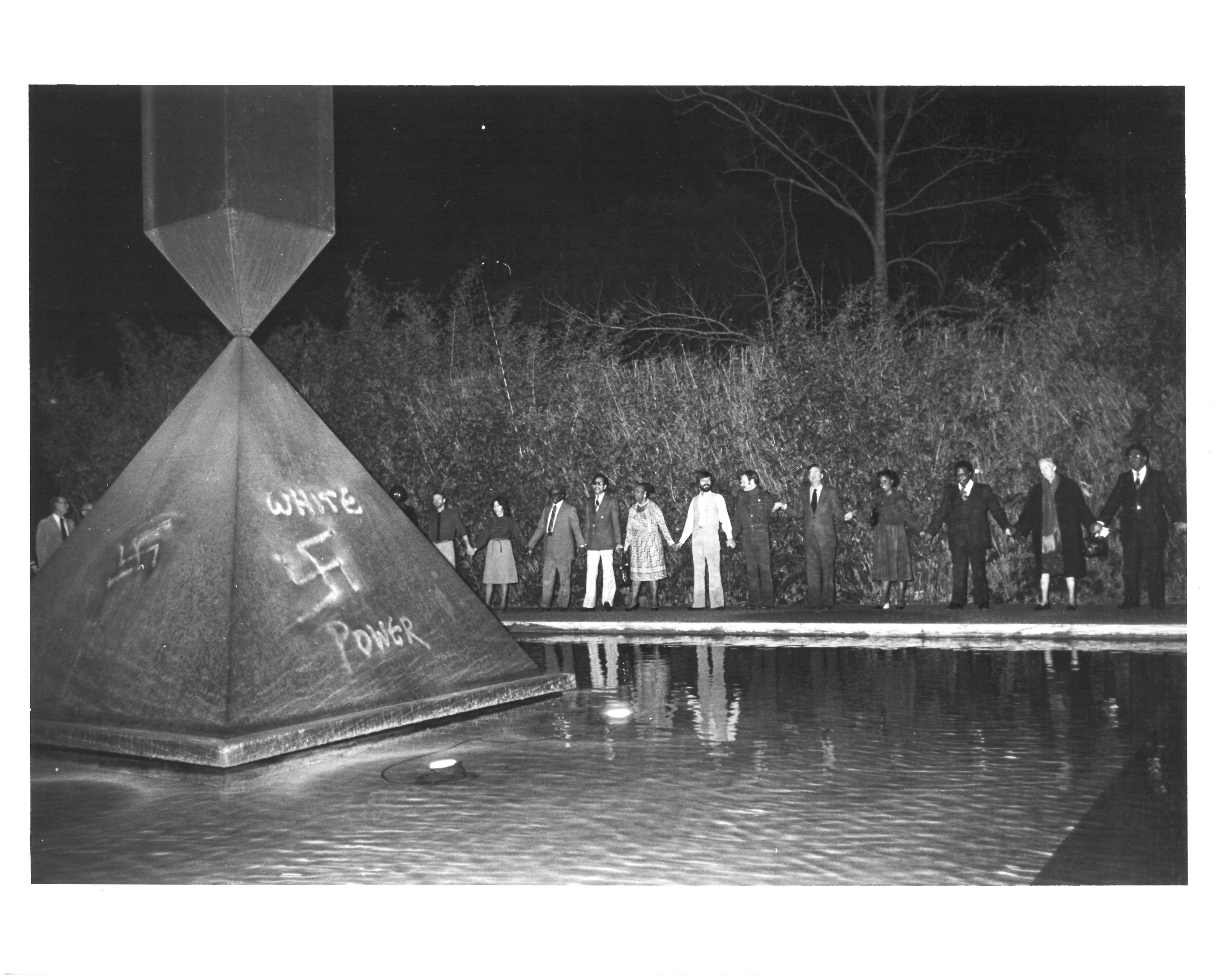

A demonstration against racism outside the Rothko Chapel in Houston, after the vandalization of Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk, January 1979. The de Menils had opened the chapel in 1971.

HICKEY-ROBERTSON/ROTHKO CHAPEL ARCHIVES

In the 80 years since the art historian Clement Greenberg noted that the upper class and the avant-garde are connected by “an umbilical cord of gold,” few art patrons have proved to be as generous, adventurous, and freethinking as the French couple Dominique and John de Menil and their children, who for decades plowed a fortune derived from the Schlumberger oil-services company into art as well as political, religious, and social causes.

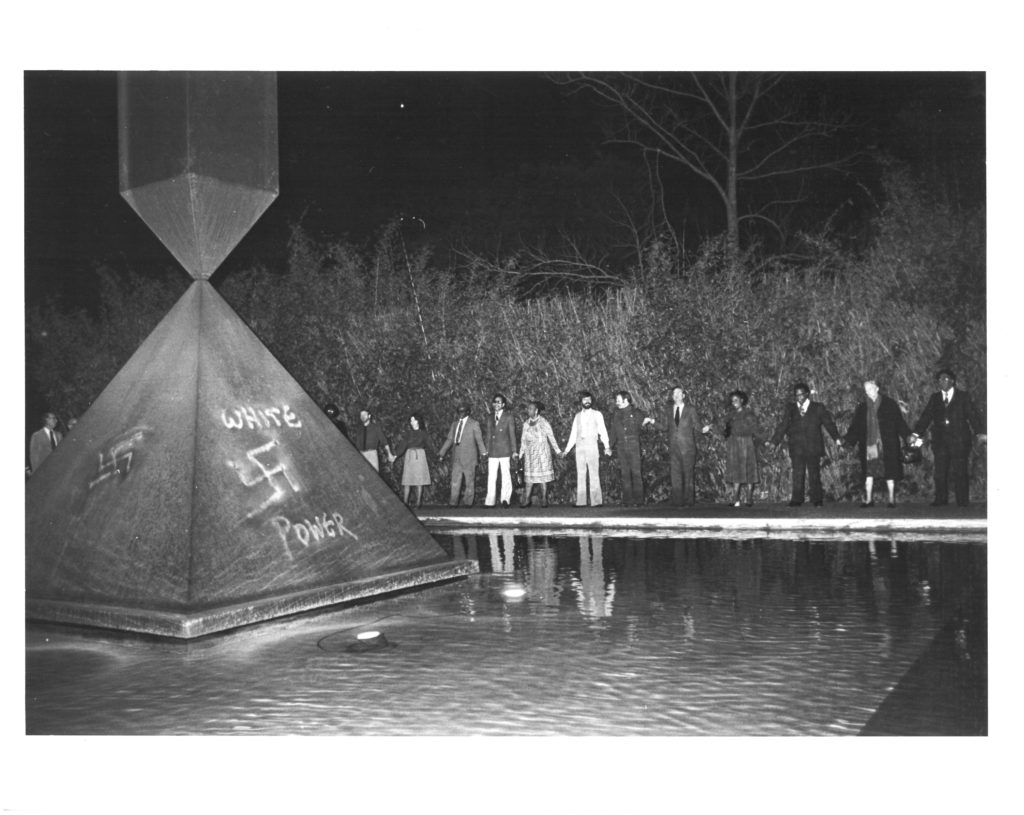

An erudite and vigorously researched new biography of the couple, Double Vision: The Unerring Eye of Art World Avatars Dominique and John de Menil (Knopf; 800 pp.; $35), by William Middleton, takes the full measure of their achievements, the well-known apotheosis of which is the Menil Collection, the masterpiece of a museum designed by Renzo Piano that opened in their adopted hometown of Houston in 1987. Free to all and utterly tranquil, the museum is the main stage for a collection now comprising more than 17,000 pieces of modern and contemporary art, plus antiquities, Byzantine art, and pieces from throughout the non-Western world.

KNOPF

“What I admire I must possess,” Dominique once said, but Double Vision is about more than just the amassing of objects. It is a tale about two lives lived very well, and with more than a little glamor. Their love affair—sparked in 1930 at a party in Versailles, almost nixed by her parents, and sustained through letters they wrote while separated for a stretch of the Second World War—is one of a few threads that would make for a good movie. The couple’s work for the French Resistance—John performing sabotage in Romania, Dominique raising funds through a little store in Caracas—is another. And the example they later set as philanthropists and collectors is vitally important to recount now: indefatigable, uninterested in trends, and committed to social justice.

Middleton has dug through archives, read voluminous correspondence, and interviewed scores of friends and acquaintances, and he provides an intimate look at the essential role that patrons can play in shaping history while fueling artists and activists. The de Menil style of patronage could be quite discreet. Hearing that Robert Rauschenberg was having cash-flow issues at one point in the 1960s, John gave him a call and asked him how much he needed to borrow. A check for $10,000 was sent over sent over straightaway. (“I never worked harder to repay a loan in my life!” the artist later quipped.)

Wanting to support Merce Cunningham’s dance company in 1967, John helped arranged a fundraiser at the Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, the home of architect Philip Johnson, who had designed the couple’s Houston home. “We’ll have dinner on cushions under the trees, fireworks and dancing to Andy Warhol’s Velvet Underground,” John wrote, and he arranged a special train from Grand Central to bring supporters to the event. Rauschenberg designed costumes, John Cage handled the music, and Jasper Johns was artistic director. It sounds like it was quite a time.

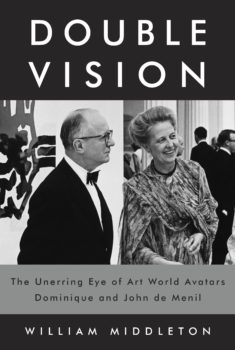

Dominique de Menil, in the early 1950s, wearing Charles James on a Charles James

chaise longue in the de Menil house in Houston.

F. WILBUR SEIDERS/COURTESY THE MENIL ARCHIVES, THEMENIL COLLECTION, HOUSTON

One day in 1967 a chauffeur arrived at the headquarters of civil-rights organizers in Houston, on a mission to buy tickets to an upcoming fundraiser at the Coliseum with Martin Luther King, Jr., Aretha Franklin, and Harry Belafonte. He handed over a check for $25,000 and explained, “Mr. de Menil told me to tell you to give away all the tickets.” (As it happened, and apparently unbeknownst to John, King had already directed the team to do just that, since the ticketing company had pulled out of the event after an office had been smoke-bombed.)

The book is filled with such tales—the de Menils providing support at just the right time and changing lives in the process. What ignited their passion? Religion, intriguingly, and especially a Dominican friar named Marie-Alain Couturier whom Dominique met in progressive Catholic circles in Paris in 1936. Couturier became a close adviser to the couple, arguing that, as their wealth grew, they should give back, in part by acquiring art for others to enjoy. Dominique explained, “He made it an obligation for us—a moral obligation—to buy good paintings, if and when we could afford it.”

Neither grew up with the vertiginous wealth that they would later amass. Born as Jean in 1904 (he changed his name after settling in the U.S.), John came from a high-ranking military family titled by Napoleon in 1813 but fallen on hard times. Dominique was born in 1908 into the Schlumberger family, a well-off Protestant clan with roots in Alsace going back at least to 1400. Her father, Conrad, and uncle, Marcel, helped develop oil-prospecting technology in the 1920s that would prove indispensable to the rapidly expanding energy industry. (However, Middleton begins her story in earnest even earlier with her great-great-grandfather, the French historian and statesman François Guizot, so the book also serves as a condensed history of post-Revolution France.)

Outside the Menil Collection.

HICKEY-ROBERTSON/MENIL ARCHIVES, THE MENIL COLLECTION, HOUSTON

John and Dominique married in 1931, and after some time as a banker, John joined the Schlumberger firm, throwing himself into his work and taking an interest in oil that one might assume to be at odds with loftier artistic pursuits. But no: after visiting oil fields one day, he wrote that he “communed with the din and the brutality, taken in by this drilling industry, one of the few remaining that still has a sense of poetry.” (He later coined a company slogan: “Wherever the drill goes, Schlumberger goes.”)

John was the more gregarious of the pair, and more eager for the spotlight. But Dominique was formidable in her own right. (One character-building exercise enacted during her youth involved her father strapping her to the front of his car with a lantern—since automobiles did not have headlights in those days.) After John died in 1973, of cancer, at the age of 69, she continued their philanthropic quests while expanding further into the realm of human rights and collaborating on a joint prize in the field with former President Jimmy Carter. (He enjoyed working with her, though he said, noting her wealth and background, “I did feel a little like a peanut farmer in the presence of some kind of semi-royalty.”)

After her husband’s death, Dominique conceived and oversaw the building of the Menil Collection, scouting numerous architects before finally settling on Piano after a single meeting. “Before we begin, I have to tell you, Monsieur Piano, that I don’t like the Pompidou Center at all,” she told him, referring to the building he had recently received plaudits for co-designing. (As it happened, she was also a major supporter of the Pompidou.) After he accepted the commission, she told him, “Welcome to hell!” Nevertheless, they apparently got along famously.

Interior view of the Menil Collection’s Oceanic galleries in the 1980s.

HICKEY-ROBERTSON/MENIL ARCHIVES, THE MENIL COLLECTION, HOUSTON

By the time of John’s passing, the couple had lived in Houston for more than 30 years while maintaining homes in New York and France, with their steadily growing collection scattered among those locations as well as the corporate offices of Schlumberger. They had not initially planned to settle in Texas, but after the oil business and World War II delivered them there, they grew attached to the place. John once wrote to Museum of Modern Art curator Dorothy Miller that “our first responsibility is in Houston. And that is where our efforts must be concentrated because here we are almost alone.”

So they brought people to town and into their lives. A fascinating cross-section of players in art history flit through Double Vision, among them Marcel Duchamp, stopping by University of St. Thomas in Houston, which the de Menils helped support for a while; filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni, wanting to “meet a lot of rich Texans”; Marlene Dietrich, who Dominique met while interning on Josef von Sternberg’s film The Blue Angel (1930); and the courtier Charles James, who designed the interior of their modernist home, to Johnson’s chagrin.

Just as remarkable as the stars involved with the de Menils, though, were the lower-profile figures that are now legends in art circles. Middleton offers up succinct biographies of figures like the Jermaine MacAgy, a renowned and colorful curator who worked at the school. (Walter Hopps, another one of those people, remembered her saying, while insisting that artworks art be lower than convention: “I want my tits right in the center of the work. Hit the tits!”). Still another is the dealer Alexandre Iolas, a major supplier for the de Menils. One day he had the wily idea of closing a sale to them of a Matisse by asking the Philadelphia collector Albert Barnes to sign his guestbook. (“This is one of the greatest Matisse ever painted,” Barnes wrote, and the de Menils decided to buy.)

The 20th-century galleries of the Menil Collection in 1987, with paintings visible by Georges Braque, Joan Miró, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso.

HICKEY-ROBERTSON/MENIL ARCHIVES, THE MENIL COLLECTION, HOUSTON

Those seeking scandal will find little in Middleton’s balanced book. The author lightly touches on rumors that John had an affair, notes that he and his wife were rather hands-off as parents (Dominique: “I will burn in hell for the way I treated my children”), and writes about some imperious behavior by Dominique when it came to managing the Menil Foundation’s finances in its later years and, in the mid-‘80s, the financially teetering Dia Art Foundation, started by one of their five children, Philippa (later Fariha Friedrich). But in those last two instances, Middleton essentially argues that Dominique made the tough-minded but ultimately correct decisions. And lest one get the wrong impression, she was not without a self-aware sense of humor. She kept a painting of a dollar sign by Warhol in her bedroom, and once told Hopps, “That is a very special icon for me. One of my most important jobs is to make sure that we always have dollars.”

“Hers is one of the noblest and most heroic lives lived this century,” the scholar Leo Steinberg remarked of Dominique, and indeed, one could list at length the works that she and John fostered. There is the ecumenical Rothko Chapel they built in Houston, with a Barnett Newman sculpture at its front dedicated to the civil-rights work of King. There are the books they funded—catalogues raisonnés for René Magritte and Max Ernst, plus The Image of the Black in Western Art, a multivolume tome published in conjunction with Harvard University. There are buildings in Houston dedicated to the art of Cy Twombly, a Dan Flavin installation, and 13th-century Cypriot frescoes acquired on the black market. (A bulletproof vest was commandeered for Dominique for those negotiations.)

But what shines through most in Middleton’s telling is the boundless curiosity of the two French visionaries—and their willingness to operate by their own rules. “What I loved about the collection is that it was utterly unconventional,” the Picasso scholar John Richardson said, noting how “how terribly conformist” most other collections he saw at the time were by comparison. That remains a problem today, with so many collectors buying up the same few artists and building seemingly interchangeable museums to display their wares. (The de Menils’ support for civil rights and humanitarian causes also contrasts rather sharply with the interests of some of today’s leading patrons and collectors, which include backing right-wing politicians, opposing efforts to mitigate climate change, and working to cut public-sector pensions.)

Dominique and John de Menil were immigrants who fell in love with the United States—its people and its spirit. (Not to mention its food: describing the rituals of barbecue, a new discovery for him in the 1930s, John wrote to Dominique, “C’est très sympathique.”) Prior to his death, the French baron opted to be buried in a Houston cemetery, rather than be sent back to France. Dominique would join him there about a quarter-century later, after passing away on New Year’s Eve of 1997 at the age of 89.

For his funeral, John specified his pallbearers, listed songs he hoped Bob Dylan might perform (a record player served as a substitute), asked that his funeral director be black, and requested that there be no eulogy. He wanted to be buried in a coffin of the “cheapest wood” and delivered to his grave by a pickup or flatbed truck. “These details are not inspired by a pride, which would be rather vain, because I’ll be a corpse for the meat wagon,” he wrote. “I just want to show that faith can be alive.”

[ad_2]

Source link