[ad_1]

Jacopo Tintoretto, The Deposition of Christ, ca. 1562.

COURTESY NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART

Jacopo Robusti, better known as Tintoretto, would have turned 500 this year. To observe this milestone, the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., currently has on view a landmark exhibition. “Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice” is the first survey of this Old Master’s boisterous corpus ever mounted in the United States. It features scenes from the Bible, tales of mythological gods and goddesses, and a group of penetrating portraits of doges, dignitaries, and distinguished women, not to mention two riveting self-portraits. Meanwhile, drawings by Tintoretto, his workshop, and his peers are on view elsewhere in the museum. You should purchase your train ticket now: the exhibition closes July 7. You also might want to consider buying a plane ticket to Venice so that you can visit the Old Master’s supersized masterpieces that never leave their respective churches, scuolas, and palazzi.

For a long time, Tintoretto was not as highly esteemed as his contemporaries Titian and Paolo Veronese or their slightly older colleagues Giovanni Bellini and Giorgione. In recent years, however, his star has been ascendant, and the paintings in D.C. make a splendid case for his newfound stature.

Jacopo Tintoretto, A Procurator of Saint Mark’s, 1575/85.

COURTESY NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART

Tintoretto, to be sure, could paint an elegant, classical picture with the best of them. He had a gift for color, and for bathing his works in light and shadow. But, among the artists associated with Renaissance Venice, he was the one who excelled at the depiction of crowd scenes, exaggerated perspectives, figures suffering from plagues and pestilence, all manner of mayhem. Dark places abound in the world he renders. If artists became television shows, you’d watch Titian and Veronese on a highbrow channel like PBS, while you’d be more likely to find Tintoretto on FX with the more action-packed fare.

Tintoretto and Venice were tightly bound together. Born in this Instagram-ready city of small islands, canals, and bridges in 1518, the artist seems never to have traveled elsewhere to make art. Rather than applying tempera to wood panels as had been common earlier, he helped pioneer the practice of painting with oil and canvas. During the mid-1550s, shortly after completing his breakthrough work, The Miracle of the Slave, the then-30-something artist executed a pair of 40-foot-tall panels for the high altar of the Venetian church of the Madonna dell Orto. (His remains would be entombed there in 1594.) In the ensuing decades, he blanketed the ceilings and walls of two floors of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice with paintings devoted to episodes from the Old and New Testaments. The most impressive work at San Rocco, a highly detailed 40-foot-long Crucifixion executed in 1565, was created for the inner sanctum–like boardroom. Toward the end of his life, Tintoretto painted the roughly 74-by-30-foot Paradise at the Palazzo Ducale, which some consider the largest Old Master painting ever executed on canvas. It would take hours to count all the figures in this gigantic production.

Jacopo Tintoretto, Saint George, Saint Louis, and the Princess, 1552.

COURTESY NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART

The NGA show presents the opportunity to watch Tintoretto evolve throughout his career, both thematically and formally. In his earliest works, the artist introduced what would be his ongoing interest in dramatic scenes and bravura brushwork. Co-curators Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman describe a self-portrait from 1546/7 in the first room as “a scruffy young painter, with an intense gaze and scraggly hair and beard—a signal that he does not have the time to spend grooming . . .” Another opening work, a mythological subject that’s hung above a doorway to indicate that it was originally a ceiling painting, also reminds viewers that the artist was making art for Renaissance spaces, not modern museums. And then there’s an unusual Conversion of St. Paul (ca. 1544) transpiring in a tumultuous landscape replete with soldiers and rearing horses. It’s not the sort of calm, contemplative setting in which you might expect a life-altering religious experience to occur.

Everywhere you look, there are majestic, full-bodied men and women in the nude or wearing elegant, splendidly colored garments with well-articulated folds and creases. They’re active figures, turning, bending, stretching, fleeing, swooning, reacting to a range of situations. St. George, St. Louis, and the Princess (1552) could not be more astonishing. Having no idea what a dragon looked like, Tintoretto transformed the animal into a frightening sea creature adapted to land. Again and again, the Venetian artist makes you want to gasp. When he portrayed five monumental figures in dramatic poses in The Deposition of Christ (1562), he hit an empathetic chord so that we, too, become as distraught.

A wonderful group of portraits carefully selected are also on view. To emphasize the personalities of the sitters (standers?), Echols and Ilchman tried to avoid showing canvases with window views and other distractions. Consequently, you become transfixed by the gaze of Man with a Golden Chain (1560) or end up gawking at the majestic fur-trimmed, crimson robe of a procurator of St. Mark’s (ca. 1575/85). Similarly, by painting a group portrait that melds fact and fiction with a strong element of time travel, you think you are witnessing Venetian dignitaries, including a trio of regal officials, adoring the Christ child.

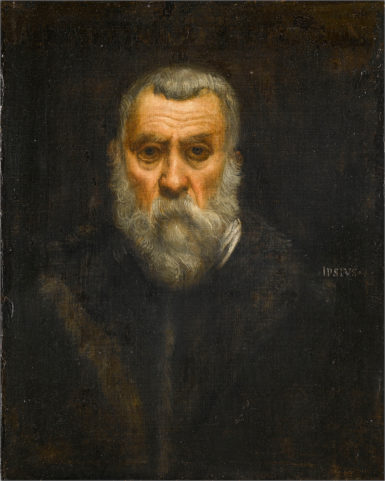

Jacopo Tintoretto, Self-Portrait, ca. 1588.

© RMN-GRAND PALAIS / ART RESOURCE, NY, JEAN GILLES-BERIZZI

Tintoretto’s fish, birds, and mammals are as vivid as his men, women, and children. The Creation of the Animals (1550/by 1553) is a case in point. As an animated God the Father, in a fluttering, wind-swept robe, conceives the first living beings, they believably swim in the sea, move along the ground, and fly in the sky.

Eventually the amorous adventures of mythological gods and goddesses and the trials and tribulations of saints and sinners give way to something darker. In the last gallery, two tall, newly restored panels from the Scuola Grande di San Roccco portray the Virgin Mary Reading and Mary in Meditation (1582/83). She’s a small figure depicted in apocalyptic landscapes of barren trees, gnarly roots, windswept leaves, and rushing waterfalls. These scenes are the inverse of the earlier conversion of St. Paul, conveyed in foreboding tones and thrilling, animated brushstrokes. An aura of light surrounds Mary’s head; moonbeams shine on the sides of some trees and a waterfall. In a catalogue essay, art historian Maria Agnese Chiari Moretto Wiel notes that the figure in each painting is “immersed and almost lost in the natural setting, in which the distinctive element of Jacopo’s late style is carried to an extreme: an extraordinarily rapid technique, using a nearly monochromatic palette.”

A late self-portrait from ca. 1588 hangs by the retrospective’s exit. It’s a small work in which a bearded face with a furrowed brow emerges from the shadows, and it calls attention to the artist’s wide-open, somewhat mournful eyes. We ourselves have just witnessed a glimmer of what Tintoretto saw and experienced.

[ad_2]

Source link