[ad_1]

Johannes Vermeer, The Astronomer, 1668, oil on canvas, 19⅝” x 17¾”. National Gallery of Art.

MUSÉE DU LOUVRE, PARIS, DÉPARTEMENT DES PEINTURES, ACQUIRED BY “DATION” IN 1982

As Secretary of the Treasury before and during the Great Depression, banker Andrew Mellon’s priority was elimination of the inheritance tax. To avoid impeachment for profiting illegally from private investments while in office, Mellon quit in 1932 to become United States ambassador to Great Britain. He then cut a secret deal with the Soviet Union to buy 21 paintings, mostly Dutch, from Catherine the Great’s collection in the Hermitage. A politically charged tax evasion investigation dogged the 1937 donation of these and 313 other artworks, and a pot of money, to create the National Gallery of Art, which opened in 1941.

The National Gallery’s first blockbuster, “Paintings from the Berlin Museums,” took place in 1948 at the request of the U.S. Army. It featured 202 artworks found hidden by the Nazis in a rural German salt mine that had been brought to the National Gallery and stored “for safe keeping” in 1945. Nearly one million people visited the exhibition in 40 days. After a 12-city U.S. tour, the works were returned to Germany in 1949.

Another extraordinary popular exhibition opened in 1963. While her husband worked on averting French nuclear proliferation, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy charmed writer/French Culture Minister André Malraux into lending the United States the Mona Lisa. The director of the National Gallery, John Walker, dropped his opposition to the project during the Cuban Missile Crisis. At the Leonardo’s unveiling in the National Gallery’s West Statuary Hall, President Kennedy told 2,000 guests, including the entire United States Congress, the Supreme Court, the members of his Cabinet, and their wives: “We here tonight, among them many of the men entrusted with the destiny of this Republic, also come to pay homage to this great creation of the civilization which we share, the beliefs which we protect, and the aspirations toward which we together strive.” Between January 9 and March 4, 1963, nearly 2 million people visited the single-painting show at its two stops: the National Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The painting returned to the Louvre as it had come, via ocean liner.

Several uneventful blockbusters later, the National Gallery opened the world’s first monographic exhibition of Johannes Vermeer on November 12, 1995. Northern Baroque paintings curator Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. negotiated for eight years to show 21 of the artist’s 35 known works. Two days after it opened, Republican radicals raging against President Clinton shut down the federal government, and hence the show. It reopened, but then an extreme snowstorm hit. Then the government was shut down yet again. Private funding and extended hours did not alleviate the madness of the crowds. Lines circled the building. A docent was robbed of a stack of free, timed tickets by a would-be scalper. The gift shop ran out of catalogues. Twenty years later, in a 2015 symposium titled The Vermeer Phenomenon, Wheelock recalled the crucial question, “How many [Vermeers] do you need to have a show?”

The answer, perhaps, is more than ten, the number of Vermeers in “Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting,” which opened at the National Gallery in October (“#VermeerDC”) and travels to the National Gallery of Ireland and the Louvre in 2018. Stanchions threaded the length of the East Statuary Hall during the show, but—like January 20, 2017—the crowd on the National Mall was smaller than expected. Sixty-odd additional works by other Dutch painters, including Gerard ter Borch, Gerrit Dou, Pieter de Hooch, and Gabriel Metsu, attended a Vermeer, centrally hung, one meme per room: #lace, #duet, #writealetter, #suitor, #doorway, #backtoviewer, #parrot. In the #men gallery, a Vermeer pendant was nearly reunited: a small, earlier Gerrit Dou (Astronomer by Candlelight, 1665, from the Getty) separated The Geographer, (1669, Städel Museum, Frankfurt) from its companion, The Astronomer (1668), which Hitler stole from the Rothschilds, who eventually gave it to the Louvre. The verso still bears a black swastika stamp.

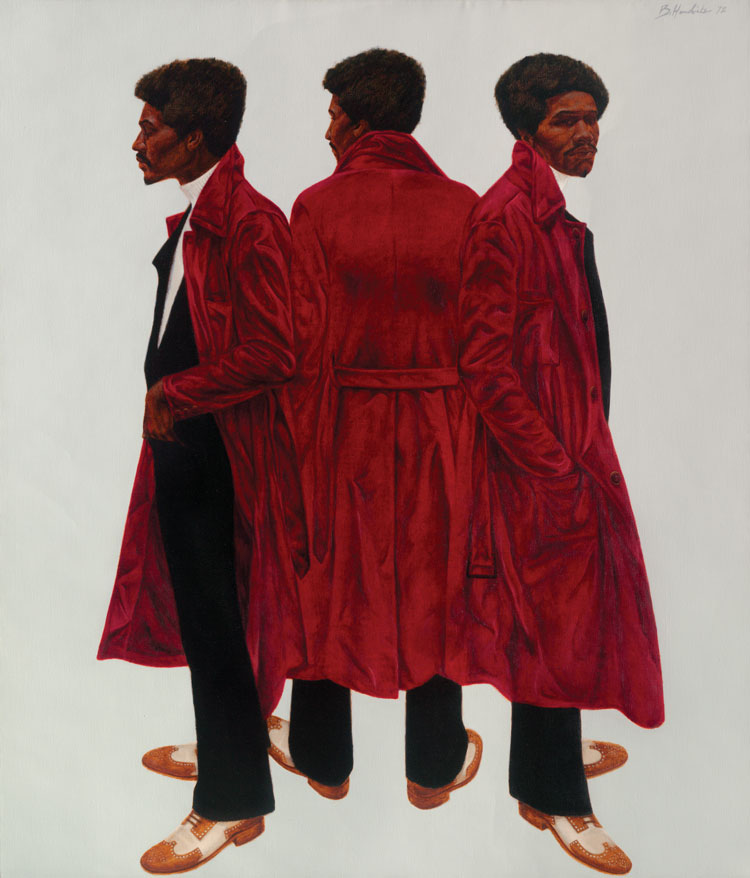

Barkley L. Hendricks, Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris, 1972, oil on canvas, 84⅛” x 72″. National Gallery of Art.

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, D.C., WILLIAM C. WHITNEY FOUNDATION

Andrew Mellon envisioned the National Gallery as the beneficiary of America’s great collectors. To get in, an artist had to be great, white, male, and dead 20 years, or Mary Cassatt. Accepting Chester Dale’s 1962 bequest of a Blue Period painting by the still-living Picasso breached but one of those barriers. In 1973, as Mellon’s highly enriched heirs were funding construction of the East Building, the Gallery acquired its first two works by living African-American artists. Jacob Lawrence’s painting of Harriet Tubman, Daybreak—A Time to Rest (1967), was an anonymous gift. Barkley L. Hendricks’s 1972 painting, Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris, was acquired directly by director J. Carter Brown, using funds provided by Michael Whitney Straight, a scion/owner of the New Republic who would have been the first chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, if he hadn’t joined a Russian spy ring while at Cambridge. The follies of youth.

This past winter, Hendricks’s triple-portrait masterpiece, all too rarely on view, presided over one of the most bracing permanent collection installations Washington has ever seen, one that filled two galleries behind Jackson Pollock’s Mural (1943), a refugee wall-surfing through eleven museums around the world since it was left homeless in 2008 by extreme flooding at the University of Iowa Museum of Art. Curator Molly Donovan’s “Bodies of Work” was a vivid exploration of the contemporary body. Kerry James Marshall’s Voyager (1992) faced Yinka Shonibare’s Girl on a Globe (2011), which was flanked by Lynda Benglis beeswax totems, an Iona Rozeal Brown painting, and Kara Walker silhouettes. With the exception of the Benglis totems, all the work was absorbed from the Corcoran Gallery, which died in 2014 of complications arising from wounds self-inflicted during the ’80s–’90s Culture Wars. Next door was the Hendricks, along with Ann Hamilton photos, portrait busts by Janine Antoni, skin-tone monochromes by Byron Kim, not-mugshots by Glenn Ligon, and fright wig Warhols, which encircled the National Gallery’s first Felix Gonzalez-Torres, a sublime silver piece from 1991 called “Untitled” (Ross in L.A.). Visitors are meant to take a print from the stack, but due to overzealous supply or anemic demand, on many recent visits it was way above ideal height. Exit is through Gonzalez-Torres’s silver bead curtain, on loan from Glenstone, the private Maryland museum of collector and trustee Mitchell Rales and his wife, Emily.

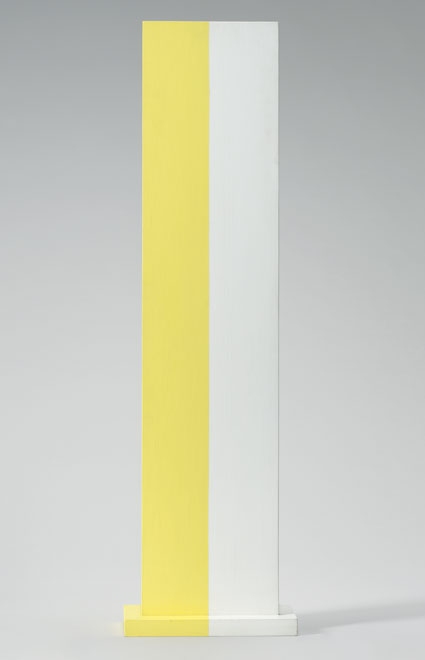

Anne Truitt, Mary’s Light, 1962, acrylic on wood, 53½” x 15″ x 7″. National Gallery of Art.

©ESTATE OF ANNE TRUITT, BRIDGEMAN IMAGES/COURTESY MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY/ANGLETON/KHALSA FAMILY COLLECTION

Up the spiral staircase designed by I. M. Pei was “In the Tower: Anne Truitt.” Local artists have long gotten short shrift in the National Gallery. Here, curator James Meyer made an argument, not (just) for the art-historical relevance of Truitt’s work—and not for a token local artist made good—but for the centrality of Truitt’s singular practice to Washington, D.C., where she made so much of her work. Meyer documents the various studio spaces Truitt maintained in D.C. and their relation to her production. Truitt’s exploration of memory and experience as embodied by color in space could not be outsourced to industrial fabricators. It matters that the National Gallery has only one major Donald Judd, and it’s painted, and was shown six months after Judd wrote dismissively of Truitt’s show of similarly minimalist sculptures. Rather than just squeezing into the historical cul de sac of the Washington Color School, Truitt makes D.C. an art capital at last.

Even with recent acquisitions of significant early work by Truitt, Meyer would be hard-pressed to make this case—and might not even have tried—without the Corcoran, which collected and showed key Truitt work. But the most intriguing case for #TruittDC comes from the tiny monument around which all of Truitt’s other works revolve. Mary’s Light (1962) is a two-toned acrylic-on-wood stela with all the scale of her eight-foot-high Insurrection (1962), but barely a quarter the size. It is named for Truitt’s best friend and frequent studio mate, the painter Mary Pinchot Meyer. Like Truitt, Mary Meyer studied with Kenneth Noland. Like Truitt, she had a breakthrough in 1961 after seeing Ad Reinhardt’s and Barnett Newman’s paintings. Like Truitt, she strove to develop a serious art practice amid the privilege and constraints faced by a woman, wife, and mother at the pinnacle of Washington political society. (Her sister was married to Ben Bradlee, of the Washington Post; she had an affair with President Kennedy.) Unlike Truitt’s, however, Meyer’s work has been almost completely invisible since her murder in 1964, which remains unsolved. On loan from family friends and on public view for the first time in four decades, could Mary’s Light point the way to discerning a new, historical Washington School?

The National Gallery opened two new tower galleries in 2016. The larger contains Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross (1958–66) in one half and, in the other, ten Mark Rothko paintings, including nine of the 198 donated to the Gallery by the artist’s children in 1986 in lieu of inheritance tax. If either half of the tower is not empty when a visitor arrives, wait a minute; it soon will be.

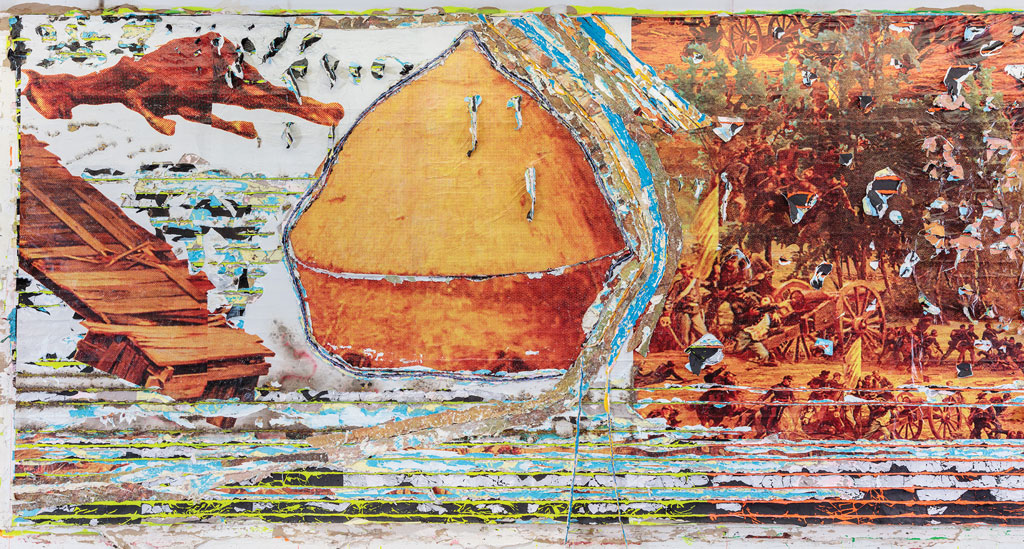

Mark Bradford, Pickett’s Charge (Dead Horse), detail, 2016–17, mixed media, installed in the artist’s studio. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

JOSH WHITE/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH

Across the National Mall, the Yayoi Kusama circus—a blockbuster if ever there was one—came and went, leaving the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden with record attendance for the year, and a pumpkin. For the second time in less than a decade, the museum commissioned an artist to make an installation out of a lobby renovation. In 2012 Barbara Kruger vinyl-wrapped the Hirshhorn’s lower-level lobby with Belief+Doubt, whose maxims and questions (“Who is beyond the law?”) are, painfully, no longer rhetorical. Kruger’s moving the gift shop out of the lobby, a curator once explained, made the museum a more attractive venue for corporate and political event rentals. Now, a new regime has turned to Hiroshi Sugimoto to fill the ground-floor lobby with a sculpture made of art furniture and a bronze gelato bar.

Long stuffed with uranium magnate Joseph Hirshhorn’s tabletop bronzes, the Brutalist doughnut’s interior corridor gallery is now the site of large-scale, long-term wall works. Mark Bradford’s eight-panel Pickett’s Charge (2016–17) abstracts layers of history, violence, and reckoning on an architectural scale. The work draws title, imagery, and ambition from the Gettysburg Cyclorama (1879–91), a 377-foot-long panoramic painting by Paul Philippoteaux depicting the climax of the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg. The spectacular painting drew large, ticketed crowds in Chicago and Boston for years before being installed in Gettysburg for the battle’s 150th anniversary. Bradford’s version is built from blown-up layers of billboard-like photoreproductions, including the occasional Monet haystack. Ropes were sandwiched in between and ripped away, opening gashes across each surface and exposing hidden strata. Some of Bradford’s channels appear burned away, not torn, as if this contemporary recounting of the Civil War were riven with fuse cord. From the installation funding credits, it appears that at least six of the panels have been pre-sold.

Puncturing Bradford’s cycle, between The High-Water Mark and Witness Tree, is the entrance to the Lerner Room, overlooking the National Mall. Reynier Leyva Novo’s 5 Nights (2014), from his series “The Weight of History,” has remained on view here since the summer of 2016. Oily-iridescent black rectangles of lithographic ink are printed on the wall, their dimensions determined by the volume of ink required to produce the signature book of various authoritarian despots. Mein Kampf dwarfs all the rest, nearly as big as the doorway itself, large enough to capture a blurred reflection of the National Archive across the Mall in its black mirror.

Back through the Kruger in the lower level lobby lies “The Message: New Media Works.” Mark Beasley, the Robert and Arlene Kogod Secretarial Scholar and Curator of Media and Performance Art, has programmed the Washington, D.C., debuts of five video installations from recent biennials, which are to be experienced in the following sequence: Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2013), a transcendent and lyrical multilayered rumination on the creation and organization of the universe, conceived during a residency at the Smithsonian; Hito Steyerl’s How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013), an increasingly depressing explication of the futility of ever eluding the neoliberal dystopian hegemony; C. T. Jasper and Joanna Malinowska’s HALKA/HAITI 18°48´05″N 72°23´01″W (2015), a multichannel documentation of a Polish melodramatic opera performed in the center of an impoverished village in Haiti that was founded by Polish conscripts in rebellion against Napoleon’s failed attempt to crush the Haitian Revolution; Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death (2016), a devastating elegy of black American life and culture, also a heartrending catharsis for a New York City art world traumatized by the 2016 presidential election; Frances Stark’s My Best Thing (2011), a numbing plunge into the soul-stripping digital void as experienced through the CG auto-animation of the artist’s interminable sex chat transcripts; it leaves a viewer begging for Kusama’s Obliteration Room.

Installation view of “The World of Jesus of Nazareth” permanent exhibit, at the Museum of the Bible.

ALAN KARCHMER FOR MUSEUM OF THE BIBLE

Museum of the Bible is a $500 million cornerstone for biblical governance planted by Hobby Lobby craft store billionaire David Green, and set into shovelfuls of money from the Christianist industrial complex. It opened November 17, 2017, near Capitol Hill, but it does not contain the 5,500 looted archaeological artifacts Hobby Lobby bought from ISIS; those were confiscated by the Justice Department, and the company was fined $3 million. Exhibits comprise other tablets and fragments, and many replicas—the actual Mesha Stele remains in the Louvre, the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum—in order that the mantle of historical authority may here alight upon these stewards of this assembled text.

The centerpiece of the museum is Experience. Visitors to the 430,000-square-foot building may wander through a cosplayer-staffed simulation of a New Testament–era town, produced at the scale of a smallish, archaic IKEA showroom. On a crowded day the effect is somewhere between the set of a pre-warp planet on Star Trek: The Next Generation and colonial Nazareth. “History of the Bible” features a TV bro in safari gear tearing across Middle Eastern landscapes in a jeep in both documentary TV and pneumatic jeep simulator formats. “Washington Revelations” is a flight simulator tour of biblical inscriptions on various Washington buildings. Many attractions involve separate ticketing.

“The Hebrew Bible” requires only time and a walk of faith. Every six minutes, 30 visitors follow the exhortations of a wizened voiceover actor with a Semitic accent (spoiler: it’s the Old Testament prophet Ezra) to reenact the creation of Earth, Man, and Israel. The 30-minute, eleven-vignette, no-photos, no-recordings multimedia spectacular resonates with similarities to contemporary art and entertainment culture. Rough-animated Adam and Eve fall (William Kentridge); silhouetted Cain kills Abel (Kara Walker); the heavenly promise of the rainbow after Noah’s flood (James Turrell, Doug Wheeler, Drake); “Go now, past the burning bush!” (Bill Viola); the Ten Commandments projected through a shadow cube (thou shalt not steal from Anila Quayyum Agha); the 12 tribes of Israel as stones stacked one on the other (no false witness: it’s Moana); and the climax—through it all, the Jews have kings David and Solomon, and kept the Torah—amid a projection-mapped Kusama-esque Infinity Room of stars. On a recent winter weekday the wait to get in was 90 minutes. The only exit was through the gift shop.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Spring 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 101 under the title “Around Washington, D.C.”

[ad_2]

Source link