[ad_1]

Lyle Ashton Harris photographed at his studio in New York City, January 2019.

ALEX LOCKETT

The video opens in a dimly lit bedroom. A voice offscreen begins to speak. “Sometimes, I feel, I guess, deprived. I don’t know. I guess I do know.” A Roberta Flack song plays softly in the background: “The first time ever I saw your face / I thought the sun rose in your eyes.” A young man with a mop of black hair in a red sweater and khakis—the speaker, presumably—walks onscreen and crawls on the bed. “What should I say?” he asks. Looking into the camera, he speaks again. After a few moments, he thinks better of it and goes to grab a chunky white cordless telephone and his address book. He spends the next hour talking with friends and family. He went dancing for the first time in a few months. He’s still processing his breakup with his boyfriend. He’s in pretty bad debt, but things are looking up: he’s going to be included in an upcoming show at the Whitney Museum.

Lyle Ashton Harris made this video in the early 1990s, when he had just returned to Los Angeles after finishing the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York. Then in his 20s, Harris had been making diaristic videos for a few years, and photographing his life as it went along. He always had a camera with him, and nothing escaped his lens: lovers in bed, friends at the beach, the Black Popular Culture Conference at the Dia Center for the Arts, the opening dinner for the “Black Male” exhibition at the Whitney, marches and moments of leisure, travels abroad, nightlife, himself post-orgasm. The characters who appear in his videos represent a roll call of artists, curators, and scholars of the period, among them Renée Cox, John Akomfrah, Iké Udé, Vaginal Davis, Dread Scott, Faith Ringgold, Gary Simmons, Nan Goldin, Catherine Opie, Thelma Golden, Douglas Crimp, Klaus Biesenbach, Cornel West, and bell hooks.

“I didn’t have a voice,” Harris told me recently. “The camera was the voice. There was an impulse to somehow create traces of that. Photography is a trace for me, to ward off that which seems ephemeral.” His pictures are evidence of a changing culture and a record of those lost to AIDS, like the filmmaker Marlon Riggs and the poet Essex Hemphill, both of whom he calls his “elder brothers.”

Riggs died in 1994, before Harris’s first gallery show in New York. Hemphill died the following year. “My work is punctuated, in a way, by who saw it and who did not, ” Harris said.

Over the course of a decade or so, Harris’s accumulation of photos and videos became so extensive—some 3,500 slides, countless hours of footage—that he eventually gave it a name: the Ektachrome Archive. When he went to Italy for a Rome Prize Fellowship in 2000, he leased out his New York studio, moved the archive to his mother’s house for storage, and forgot about it until 2013, when he got a call from artist Isaac Julien. One of many who appear in the collection, Julien was interested in using some of Harris’s photos of him for a book associated with Julien’s film project Ten Thousand Waves (2010). This spurred Harris to start watching the archive’s old camcorder videos of himself at home talking to friends and family. He was slightly embarrassed by seeing his younger self being so candid. The videos had been his way of “getting into my own face, like I was in other people’s faces.” He found in them “a certain freedom, a nakedness—and queerness—a vulnerability.” Harris had published only a handful of images from the archive before, and he found himself wondering what else he could do with it.

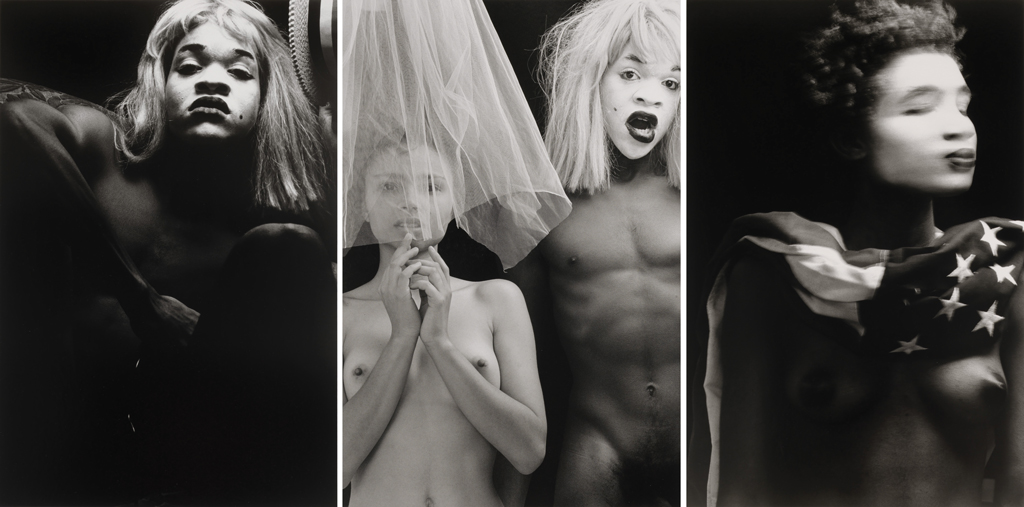

Lyle Ashton Harris, Americas, 1987–88, gelatin silver prints, triptych.

©LYLE ASHTON HARRIS/GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, NEW YORK PURCHASED WITH FUNDS CONTRIBUTED BY THE PHOTOGRAPHY COMMITTEE

Harris, now 54 years old, shaves his head and often wears thick-framed black glasses that he takes off during moments of deep thought. At a time when many artists are turning to work exploring issues of identity, he is a veteran. Deborah Willis, an artist and photography scholar who has known Harris since the ’80s, talks about the importance he places “on being visible, and not necessarily where people talk about hyper-visibility. It’s about staying present and using the archive to code and decode black stories. That’s been an essential frame for him. That’s why his work has an impact. He’s in your face with it.”

Harris was born in New York City and grew up in the Bronx. His parents separated when he was around seven. He was close with his mother’s family, particularly her parents, a well-to-do couple who were prominent members of the historic Bethel AME Church in Harlem. James Van Der Zee, the Harlem Renaissance photographer, took their portrait on their wedding day in 1932. Albert Johnson Sr., Harris’s grandfather, was an economist with a passion for photography. Over the course of his lifetime, he produced some 10,000 slides while experimenting with the era’s most advanced technology, Kodak’s color Ektachrome film, and shooting hours upon hours of footage on Super 8 film.

“My grandfather amassed thousands of slides, documenting his friends and family, extended family, church gatherings, still lifes of flowers,” Harris told me in his Chelsea studio, a mostly tidy space with the crisp white walls of a photo studio, accented by clippings of his photography and collage work. “He had a keen sense of observation. There was a modeling there for me in terms of thinking of the image. ”

Harris’s oldest cousin, P. J., who died in a car crash when Harris was seven, was also a photographer—a “superb black-and-white portraitist,” the artist said. (One of P. J.’s portraits of Harris appeared on the invitation for his first New York gallery show at Jack Tilton in 1994.) Though Harris can’t remember when he first picked up a camera, he had one as a child and, in any case, was “shooting all along.”

Two years after his parents separated, Harris’s mother, Rudean, a chemistry professor, took sabbatical to work for Tanzania’s Ministry of Education. In Dar es Salaam, she opted to send Lyle and his older brother, filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris, to an English-speaking Swahili school instead of a private international one. “Being in a country where there were black people in power, it permeated every aspect” of life, Harris said, and allowed him to form “a more global perspective on the most basic level around notions of beauty and identity.” It was a sharp contrast to his previous parochial school with its “trauma in terms of being young and being identified as ‘queer’ before I really knew what that was and before I had claimed that identity.”

[Read more from the Spring 2019 edition of ARTnews: “The Name of This Issue Is Not Queer Art Now.”]

Harris went to college at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, where he started out as an economics major. He was good at math, and he figured such a choice was a path toward success. Not long into his time at Wesleyan, he visited Amsterdam, where his brother had gone to pursue a post-undergraduate fellowship and was living openly with a boyfriend. There, Harris encountered an article about Andres Serrano’s photography, and he devoured writer and filmmaker Allan Sekula’s 1984 book, Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works 1973–1983, a seminal Marxist critique of photography’s relationship to consumerism. He also realized that, after Tanzania, he had retreated into himself. “I became more fear-based and was finding a particular trajectory that would have been safe,” he said. “Studying economics was one way. I went over [to Amsterdam] and didn’t want to be IZOD prep when I came back, so I dropped out of school and came out.”

In New York for the semester he took off, Harris immersed himself in the potent cultural hotbed of the downtown scene in the 1980s. He started going to Area, a club frequented by black and Latinx men, and waited tables at Patisserie Lanciani in SoHo. He met Jean-Michel Basquiat and Robert Mapplethorpe. He took a photography class at the Fashion Institute of Technology and a French course at the New School. When he returned after a few months to Wesleyan, his personal style had changed. He dressed androgynously, like a punk Boy George; an agnès b. sweater of his mother’s was a favorite. He switched his major to art.

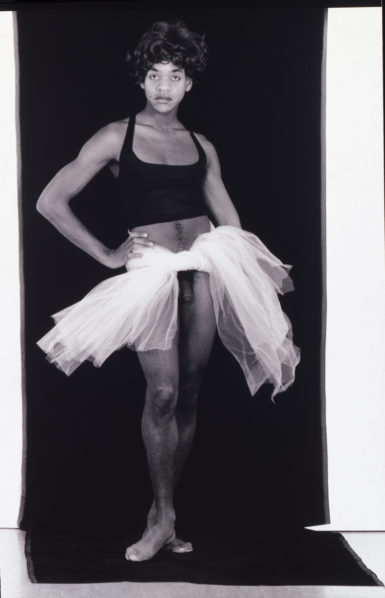

Lyle Ashton Harris, Constructs #10, 1989.

©LYLE ASHTON HARRIS/COURTESY SALON 94

His brother visited, bringing wigs and the makeup kit that would lead to Harris’s breakthrough black-and-white series, “Americas,” made between 1987 and 1988. In one photograph, the central panel of a triptych now in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum, Harris posed naked, wearing stark white foundation on his face and a light-colored wig. Next to him a naked woman’s face is obscured by a piece of tulle floating down from above. In another picture, his painted white face is blurred mid-action, screaming or laughing. In a third, a close-up of his face, he wears a tilted straw hat. The images recall harlequin figures and minstrel shows in reverse: blackface becomes whiteface.

After Wesleyan, Harris went to the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia for his M.F.A. His time there was not easy. He was one of only a few students of color in the graduate program. A professor told Harris that he couldn’t understand his work because he had not grown up in a black community. Looking for a way forward, Harris made a black-and-white photograph in which he wears a wig, a fish-scale-pattern leotard, and Doc Martens. Underneath he wrote “FAGGOT” in red lipstick. When he showed it during one of Allan Sekula’s famous hours-long critiques, “it caused a rupture,” Harris said, even in the liberal environment at CalArts. The work was “very much a product of that particular experience in terms of claiming my queer identity in a big, graphic way.”

That photograph led Harris to what he called his “Constructs,” life-size black-and-white photographs that show him, once again in whiteface, standing in front of a length of black fabric that cascades from the ceiling. In one, he is naked with his arm raised in an almost dance-like pose. In another, he stares directly at the camera, hand on hip, in a short curly wig, black tank top, and white tutu parted to reveal his genitals.

“It’s a social critique of notions of passing and notions of beauty. Clearly, I’m not trying to pass,” Harris said. “I had something I wanted to say. I was part of the formation of what it meant to be African-American and queer and out within a historical legacy—a shift had taken place around issues of race and sexuality in that the two could not be separated.”

At the time, CalArts was attempting to diversify its roster of visiting artists and lecturers. Among them were artists Marlon Riggs, Isaac Julien, John Akmofrah, and Coco Fusco, as well as black feminist author bell hooks. Riggs’s 1989 experimental film Tongues Untied was “revelatory” for Harris; it helped him develop a critical language and find a community he didn’t know he needed. Harris cultivated friendships with Riggs, Julien, Akomfrah, and hooks, who would in turn introduce him to a larger community of black artists and thinkers, including poet and activist Essex Hemphill and cultural theorist Stuart Hall.

“I had a family but something else was developing,” Harris said. “There was an insatiable need to try to create a language for something that I felt was there, that was real to me. I felt that Essex and Marlon had a language that I did not have. It was a language out of necessity. It was what sustained me.”

Lyle Ashton Harris, Sisterhood, 1994.

©LYLE ASHTON HARRIS/COURTESY SALON 94

Harris’s introduction to the mainstream art world came in 1992, when he returned to New York after graduating from CalArts and participated in the Whitney Museum’s prestigious Independent Study Program. Shortly after, he began work on a series called “The Good Life,” in which he traded the stark black-and-white of the “Constructs” for vibrantly colored dye-diffusion Polaroids, using the red, black, and green of the Pan-African flag as a palette. In these portraits, Harris’s given family and his chosen family exist in harmony, fully themselves. It’s a vision of black life that is exuberant, proud, and unabashedly queer. One picture shows Harris with his brother and mother; three, titled Brotherhood, Crossroads and Etcetera, show the Harris brothers nude, in makeup, embracing. In Sisterhood, Harris poses with a friend, photographer Iké Udé, who sits on Harris’s lap; both are regal in tailored suits and makeup. In The Family, Harris poses with another friend, artist Renée Cox, and her young son. Both adults are in drag, Cox with a mustache and checkered blazer, Harris wearing red lipstick and a red headband.

The Whitney program gave Harris a platform from which to garner both commercial and curatorial interest. Lia Gangitano, a curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston at the time, included his work in her group exhibition “Currents ’93: Dress Codes.” Gallerist Jack Tilton offered him a solo exhibition at his New York gallery, where Harris debuted “The Good Life” in 1994. Later that year, Harris’s “Constructs” would be included in the groundbreaking exhibition “Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art,” curated by Thelma Golden at the Whitney.

“Black Male” was a watershed. Thomas J. Lax, who worked for Golden at the Studio Museum in Harlem for seven years before becoming an associate curator of media and performance at the Museum of Modern Art, remembers seeing it when he was nine. The show, he said, was “a quake, a shake . . . It foregrounded questions of identity and identification but in a way that was not about stretching out terms of inclusion and exclusion. It was a show that was thinking about race and gender, and particularly blackness and masculinity, as key terms for thinking about our culture in the United States.”

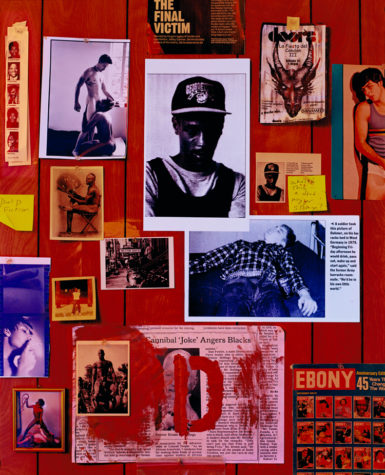

Lyle Ashton Harris, The Watering Hole VIII, 1996.

©LYLE ASHTON HARRIS/COURTESY SALON 94

In the years after that exhibition, Harris became interested in showing the vulnerability of the black male body. He found an instance of it in one of the era’s most horrifying episodes. In 1991 Harris had taken his mother to a Richie Havens concert in Los Angeles. They were accompanied by a family friend, who mentioned that a serial killer named Jefrey Dahmer, a white man, had been arrested in in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in connection with the murders of 17 men and boys, most of whom were black, Latinx, and Asian. Harris used Dahmer’s story in 1996 as raw material for his series of nine photomontages, “The Watering Hole.” Dahmer had found his victims in bars and malls, at bus stops and adult bookstores, and lured them back to his apartment, promising beer or money in exchange for posing for nude photos. He drugged and strangled them, performed necrophilia and then dismembered them, keeping some body parts as trophies.

Harris gathered news and photo clippings related to the crimes, as well as his own personal photographs, Post-it notes, album covers, images of sex, film stills, a postcard reproduction of a Basquiat painting, the American flag, and advertisements for all-male spas. He tacked these items to a wooden panel and shot them in eerie red lighting. Among Dahmer’s crimes, he had engaged in cannibalism. In this, Harris found a metaphor. He was interested, he said, in “how we all are implicated in that notion of the consumption of the other.” In 2013 the art collector and patron Agnes Gund acquired a full set of “The Watering Hole” series for MoMA. “His work is very arresting,” she said. “You don’t forget what you’ve seen.”

A few years after “The Watering Hole,” Harris, who had shot for magazines in the past, was on assignment for a New York Times Magazine article that looked at racism and anti-Semitism in European soccer. He stumbled across an advertisement in which Zinedine Zidane, a French player then at the peak of his career, was receiving a pedicure from an unnamed black player. The photograph’s composition recalled that of Manet’s 1863 painting Olympia, which shows a black maid tending to a nude white woman. Harris made the Zidane image the centerpiece of a sprawling wall collage of hundreds of images titled “Blow Up,” the first iteration of which he presented at Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago in 2004. The series “allowed me to engage disparate images I had been either collecting or creating for more than 20 years,” he wrote at the time. “I had finally found a means to say many things at once as opposed to distilling them into single images.”

Jennifer Blessing, a senior curator of photography at the Guggenheim Museum, sees Harris’s collage and photomontage work as “a personal history. It’s a kind of self-portraiture through objects, photographs, and papers. After all these years, it was so prescient, as a technique and a way of working that a lot of people have been doing in the last ten years or so.”

Lyle Ashton Harris, Once (Now) Again, 2017, installation view at the 2017 Whitney Biennial.

©LYLE ASHTON HARRIS/COURTESY WHITNEY MUSEUM

When Harris went back to his Ektachrome Archive, in 2013, he was stumped as to how, exactly, he should exhibit it. Frame the photographs, and show the videos on monitors? Make a series of slide presentations? In the end, he decided to make it into an environment that a viewer could enter, a room-size multichannel video installation. The work premiered at the Bienal de São Paulo in 2016, and the following year, curators Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks included a new iteration of it in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. At the Whitney, large screens near the entrance of Harris’s Once (Now) Again shuffled through images from Harris’s personal and public life—memories of the mundane and the unforgettable, moments of joy and pain. In the rear section were looped videos of him at home. All of it was set to music by Grace Jones.

What struck Lew about Harris’s approach was his “thinking about how the image is constructed, how identity is constructed, how one performs in front of the camera,” and how he treated the Archive not as a static repository of images, but as a living document. “It’s somebody who was so involved with the identity-politics work of that day looking back at our recent past and then making work that speaks to today,” Lew said. “We’re all so used to training the camera back onto ourselves now, but, in a way, Lyle anticipated that. I see it as a bridge between these different moments.”

Blessing, the Guggenheim curator, sees the Ektachrome Archive and Harris’s Whitney installation as showing a love—often tinged with loss—for his subjects. “There’s an idealism but also a realism because this is his community,” she said. “It’s about visibility. That was at the root of it initially, and it continues to be. There’s a certain added urgency, given our current political situation, to hold onto work like Lyle’s for the sake of one’s sanity.”

Last year, Lia Gangitano, the “Dress Codes” curator, showed part of the Archive at Participant Inc, her nonprofit space in New York. There is an element of nostalgia to the images, she said, but “I don’t think his whole motivation in revisiting those images is nostalgic. It correlated that material to something new that brought forward the sense of community and political activism and solidarity that was radically moving something forward in doing collective work around blackness. It was a force.”

At the Whitney, Harris noticed that a younger generation responded emotionally to the Archive. Speculating as to why, he attributed the reaction to commodity fetishism, selfie culture, and “the paradox of social media and the culture in which we live that in a lot of ways staves off real intimacy. We’re so used to a certain type of ‘Insta-macy,’ which is instant and based on intimacy, when in actuality it’s not.”

For his latest series, “Flash of the Spirit,” Harris worked with a suite of African masks, some of which he had seen decades before at the house of his uncle. In photographs first shown last fall at Salon 94 gallery in New York, Harris poses in idyllic outdoor spaces throughout the Northeast, wearing the masks, and often holding transparent sheets of colored glass. In one picture, he rests against a leaning tree, naked save for a circular mask nearly twice the size of his head. In another he wears a fierce-looking mask trimmed with blond straw that streams down to his navel. Donning the same visage, he reclines like an odalisque on the lush bank of a lake. Though his body shows certain signs of age, he has an ease and calmness that wasn’t there when he was young.

“It’s something different to show yourself, to show your ass, literally, when you’re in your 50s than when you’re in your late 20s,” Lax, the MoMA curator, said. “There’s an improvisation there, a theme of working out these aesthetic questions that he’s been working with for a long time.”

Questions will always remain, and that’s part of the point. “Part of the essence of my work,” Harris said, “is its potency in the realm of ambivalence, of the uncertainty of its not being such an easy answer.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of ARTnews on page 38 under the title “Out Side In.”

[ad_2]

Source link