[ad_1]

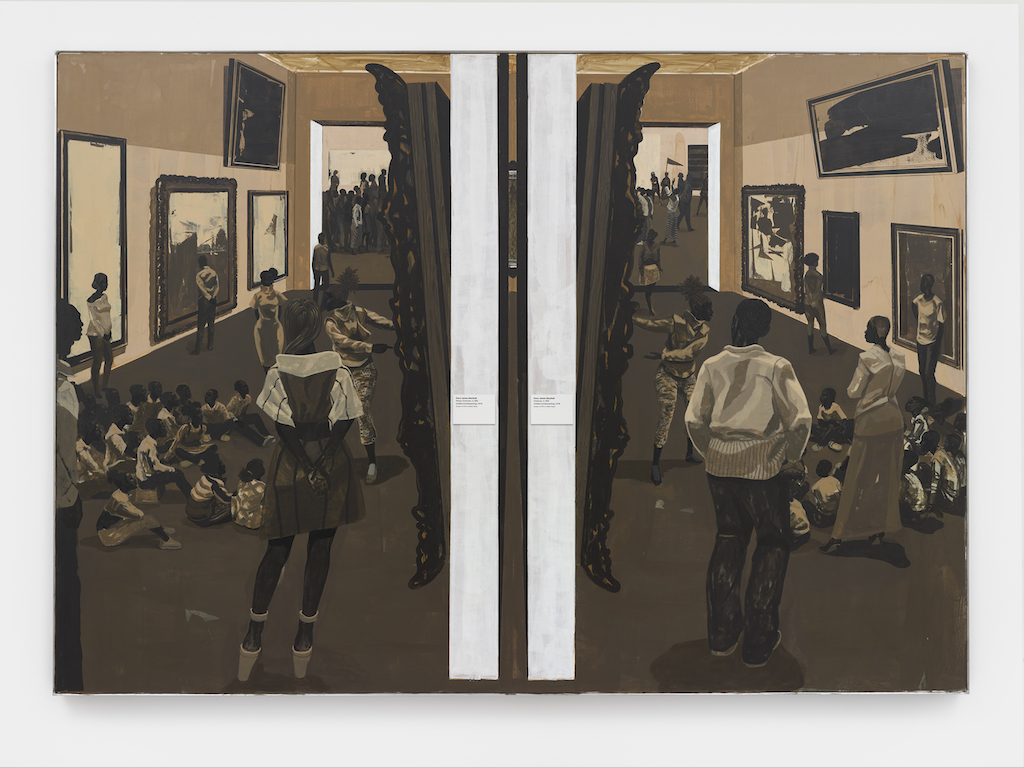

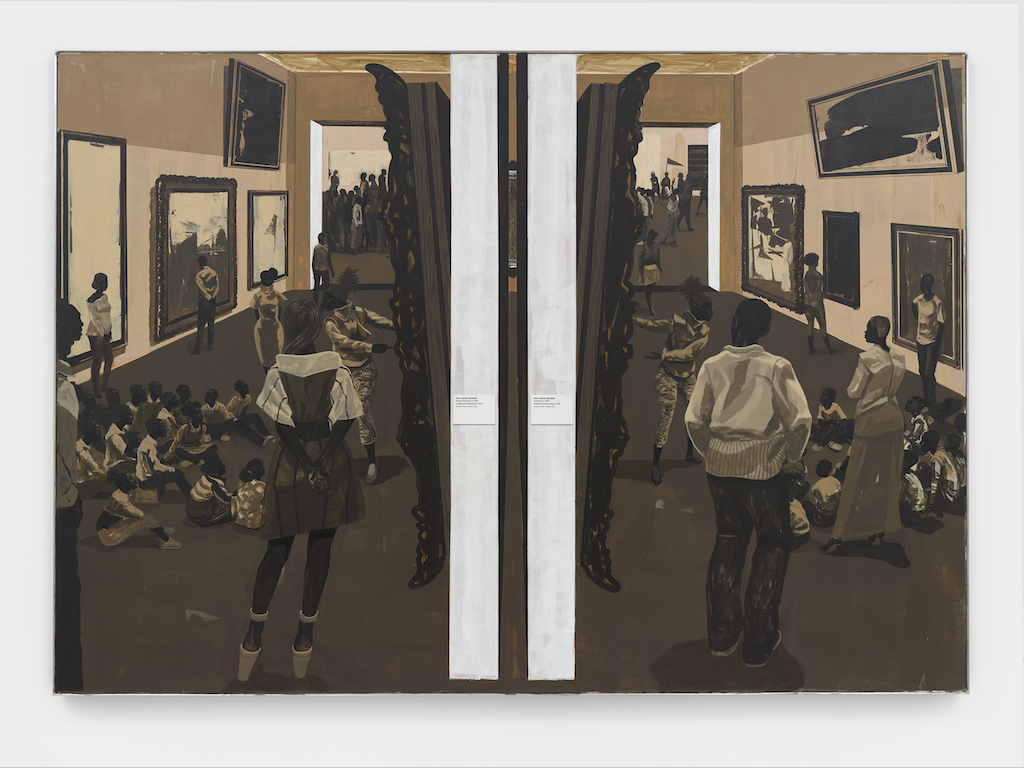

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Underpainting), 2018, acrylic and collage on PVC in artist’s frame.

©KERRY JAMES MARSHALL/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER

In a conversation with curator Mark Godfrey at Tate Modern this past May, the artist Kerry James Marshall described his signature style as experimenting with a “chromatically diverse black.” He spoke of how, in most artworks, “black is fixed, unmalleable, and singular.” He’s interested, instead, in its many tones: Ivory Black, Mars Black, Lamp Black, and Vine Black, to name just a few.

London’s Frieze week welcomed an international audience to Marshall’s first exhibition of new work since his acclaimed museum retrospective opened at David Zwirner in London. (The show runs through tomorrow.) Under the title of “History of Painting,” Marshall expands on his personal and public conversation with representational painting. Over two floors, Marshall addresses the history and function of applying paint, pigment, and color to a solid surface through still life, landscape, abstraction, and portraiture, his most acclaimed genre, and one which continuously questions our understanding of beauty, taste, and power. With this Marshall has produced a “counter-archive” for the history of Black figures in Western pictorial tradition, inscribing these figures within a new trajectory.

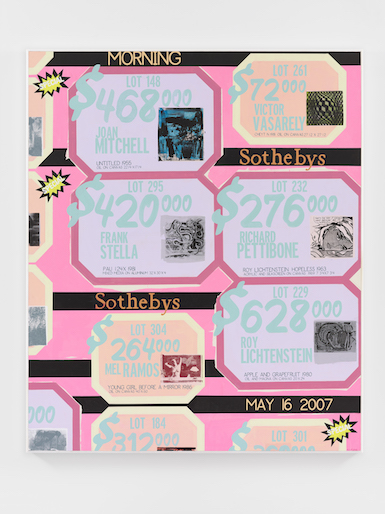

Kerry James Marshall, History of Painting (May 16, 2007), 2018, acrylic on PVC in artist’s frame.

©KERRY JAMES MARSHALL/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER

The show takes its name from the three-canvas work History of Painting (2018), for which Marshall appropriates the format of almost-neon-colored supermarket circulars. The everyday household goods typically advertised here are replaced with auction results. Each clipping represents a different auction house that held a sale in early 2007, when the art market was nearing a new peak, according to many experts. One painting illustrates the Swann Auction Galleries, one of the few auction houses that regularly hosts sales of work by African-American artists. Marshall is asking: Where do paintings end up being after their original use? Are they fated to simply be commodities?

The large-scale canvas Untitled (Underpainting), 2018, which is one of the show’s shining stars, likewise turns its eye toward art history. Marshall started the painting by applying a layer of burnt umber, and its warm brown glow remains visible in the final product, an image of Black people of various ages and genders in a museum, its holdings hung salon-style. (That technique is known as underpainting, which was used frequently by Renaissance masters.) Some adults pause in front of artworks and contemplate them with deep concentration, while others stand back and observe the whole scene. The most alluring characters are the school children who sit on the floor with their legs crossed, intently looking upward at their Black woman instructor.

In its grand scale and subject, Untitled (Underpainting) recalls the 23-by-10-foot mural Knowledge and Wonder (1995), which the City of Chicago commissioned for $10,000 for its Legler Branch Library. The mural, which also depicts Black men, women, and children in an educational setting, was on display there for two decades, and was set to be sold at Christie’s in New York this month for an estimated $10 million–$15 million. In October, Marshall expressed disappointment over the planned sale, telling ARTnews, “You could say the City of Big Shoulders has wrung every bit of value they could from the fruits of my labor.” Photographer Dawoud Bey also took to Facebook to air his grievances, and many more art practitioners made their concerns known. Earlier this week, the painting was withdrawn from the auction, and it will remain on view, free of charge, all in Chicago’s West Side. There, the work has been—and will continue to be—essential for the community.

A young person’s first introduction to viewing and making contemporary art typically comes through basic exercises in early education, though whether this routine is sustained over time is influenced by more factors than can readily be named. Knowledge and Wonder will likely spur on many young minds with an imagination for a world of wonders in Chicago. At Zwirner in London, more new works with that potential power are on view. The question now is: where will they end up?

[ad_2]

Source link