[ad_1]

During Hurricane Katrina, Jacqueline Patterson, the director of the NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice Program, was watching the news, seeing Black people on roofs waving anything they could find to beg the helicopters above to save their lives. These same Black people would later be demonized as “looters,” simply for trying to get what they needed to survive in the aftermath of a natural disaster when their government left them to die.

It is this type of injustice, inflicted upon Black people across the globe, that makes Patterson stand firm in an undeniable truth: Racial justice and climate justice are one and the same, and have been for centuries.

“The same drive that drives one group to oppress others is the same drive that drives others to recklessly extract from the earth,” Patterson told HuffPost.

“Being dominated and exploited to serve a wealthy white few” is something Black people share with the planet, she said.

Right now, #BlackLivesMatter is all the rage. Brands and corporations are clamoring to proclaim their commitment to the Black Lives Matter movement, and news outlets and organizations are seeking out more people who can speak about race and climate.

But racial justice and climate justice have always been intertwined. For Black and Indigenous people, climate destruction has been with us for a long time, as our communities have borne the brunt of the climate crisis.

Climate justice activists are not only fighting for the planet, but for their very survival.

Jacqueline Patterson, NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice Program

One reason for this disproportionate impact is that “communities of color are zoned into poorer neighborhoods that often have worse pollution and less access to clean water,” said Thanu Yakupitiyage, U.S. communications director at 350.org, an international movement that aims to replace the fossil fuel industry with renewable energy.

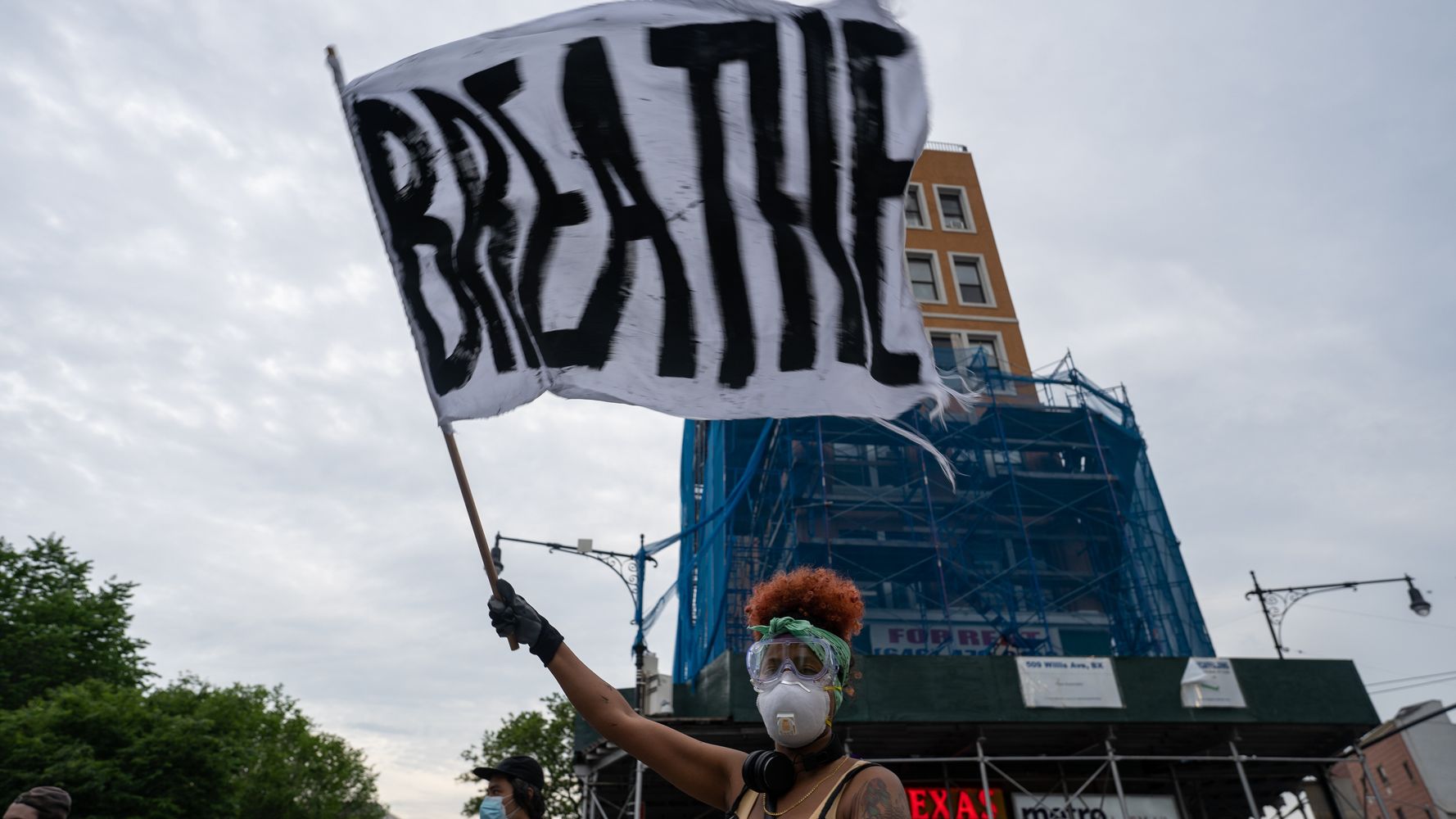

Consider Mott Haven, a 97% Black and/or Latinx neighborhood in New York City’s South Bronx, sometimes nicknamed “Asthma Alley.” Residents there “need asthma hospitalizations at five times the national average and at rates 21 times higher than other NYC neighborhoods,” The Guardian reported.

Several highways and bridges, a Fresh Direct warehouse where hundreds of trucks cycle in daily, a newspaper printing press for The Wall Street Journal and New York Post, a FedEx depot and a waste transfer station contribute to the area’s abysmal air quality, which can make Asthma Alley deadly for Black and Latinx people.

Yakupitiyage says that this strategic placement of environmentally destructive outposts of capitalism is something we see in Indigenous communities as well. “Routes of pipelines are put closer to Indigenous lands than white communities, because they know the danger of them,” she said.

Institutions and corporations completely aware of the danger decide to place the most marginalized people at the front lines. And when those people protest against this injustice, like at Standing Rock Reservation in 2016-2017, they are met with brutal police violence.

This is why, Yakupitiyage points out, “Our demands in the climate movement are not separate from calls to defund the police. Our work in the climate crisis is also about divesting from white supremacy in order to create a world that’s rooted in equity and care.”

People often say that the climate movement is “too white.” But it isn’t; it merely appears to be. The real climate movement is global, led by Black, Indigenous and other colonized and racialized people. But white climate activists and environmentalists are usually the ones uplifted and praised, while those most affected by climate change are pushed to the sidelines, even as they risk their lives to do this work.

“The folks that are in large organizations, with large budgets, are the ones that are being seen. And being seen equates to people assuming that these are the people doing the work and this is the movement,” Patterson told HuffPost.

Much of this is a matter of resources, she said. “Climate justice activists are not only fighting for the planet, but for their very survival. The separation between mere environmentalism and climate justice comes when there are monied organizations that are financed, as opposed to people that are doing this because it’s their own communities. They have to do the work, they’re called to it.”

Taylor Morton, the environmental health and education manager at WE ACT for Environmental Justice, has felt called to the work since childhood. “I grew up in South Carolina, in a family that really coveted outdoor spaces but also had to balance what it means to be Black outdoors,” Morton said.

Morton first learned about environmental justice and conservation while hunting and fishing, gardening and farming, a lot of which came from their family’s painful history as sharecroppers and slaves.

There’s a history of decoupling environmental issues and race issues. But if we don’t think about climate and climate solutions in the same vein as thinking about other solutions to injustice, we’re never going to succeed.

Thanu Yakupitiyage, 350.org

When the climate movement decenters Black and Indigenous people and other communities of color, it’s extremely dangerous for us all. Making the connection between racial justice, climate justice and economic justice is the only way we will preserve human life on this planet.

“I find it frustrating when white climate-concerned people don’t see these connections,” says Yakupitiyage. “There’s a history of decoupling environmental issues and race issues. But if we don’t think about climate and climate solutions in the same vein as thinking about other solutions to injustice, we’re never going to succeed.”

The climate movement needs to elevate and prioritize Black voices. But it needs to do so in an equitable way, not a shallow one. The difference between tokenizing Black climate activists and respecting them is even more important today. Being tokenized or only recognized when the topic of whether we deserve life is trending on social media can be “frustrating and demoralizing,” Patterson says.

“Those relationships can become extractive, although some folks legitimately recognize the problem and want to do the right thing. But some just want your body or your face, for op-eds or marches.”

And when Black climate activists are tokenized, we often end up repeating the same basic things about the intersection between race and climate over and over. It’s so frustrating to have to explain these concepts to white people constantly.

The esteemed Black writer Toni Morrison once said, “The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.”

Being a Black person in the climate world is a lot like that. We spend so much time trying to prove the obvious — that racial justice and climate justice are one and the same — that it can sometimes keep us from focusing on more revolutionary and groundbreaking work.

To be frank, trying to convince white people to care about the destruction they caused is killing us all, because it’s a distraction. Racial justice and climate justice are intertwined; this is an indisputable fact. Now, what are we going to do about it?

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to [email protected].

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link