[ad_1]

Huang Yong Ping.

BRUNO BEBERT/EPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

Huang Yong Ping, the Chinese artist whose propensity for provocation allowed him to address taboo subjects in China and beyond with audacity and wit, has died at 65. His death was confirmed by Gladstone Gallery, which represented him in New York and Brussels. A representative for the gallery did not immediately state a cause of death.

In his sly installations and sculptural work, Huang often melded techniques derived from the history of Chinese art and international avant-garde movements alike. His ability to deftly combine seemingly opposed methods of art-making made him one of the foremost artists in an emergent group of Chinese artists during the late 1980s.

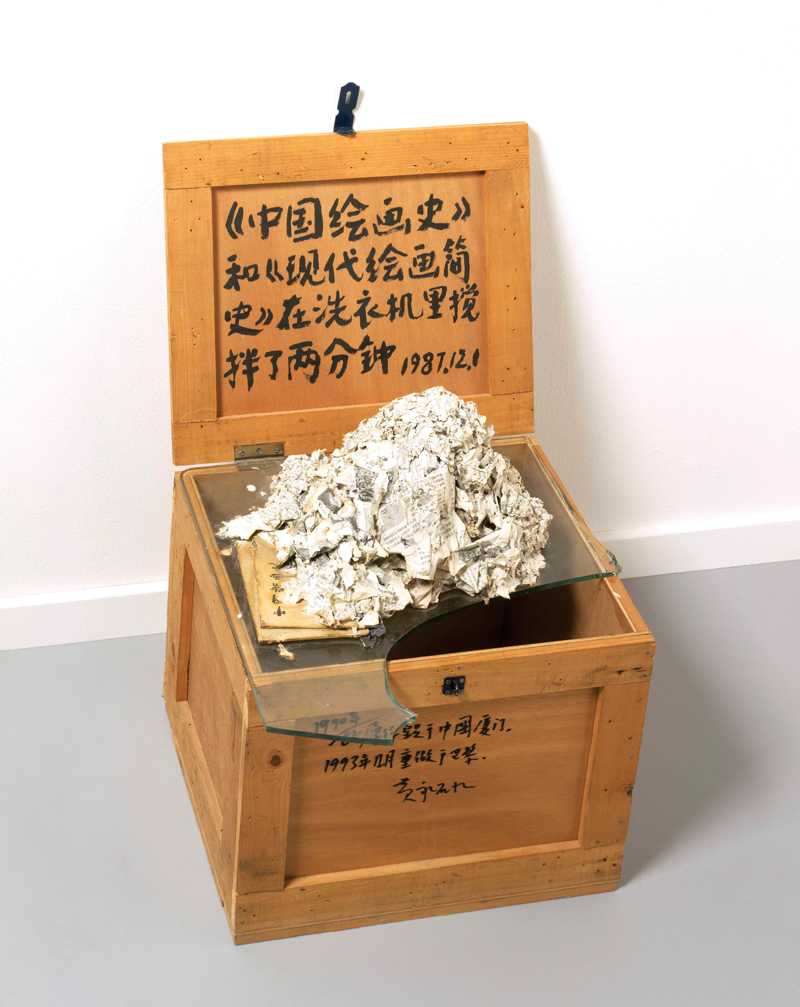

Like his colleagues, Huang chafed at the boundaries surrounding what could be presented as artwork, in the process addressing eroding traditional mores and the Westernization of the country he called home. Among his most famous works is The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modern Western Art Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes (1987), for which he put copies of Wang Bomin’s History of Chinese Painting and Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting (the first book about modern art history translated into Chinese) into a would-be laundry cycle. Huang then placed the pulped remains of the water-pummeled tomes atop a piece of glass, put it on a teabox, and exhibited it as an artwork.

Huang Yong Ping, The History of Chinese Painting and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes, 1987 (reconstructed 1993).

WALKER ART CENTER

What could have been a wry, ironic gesture became, in Huang’s hands, an iconic statement about globalism and the merging of thought processes. It alluded to the anarchistic quality of Dadaist artworks, which proposed that reason was meaningless in modern society and placed an emphasis on concepts over aesthetics, and it also showed how Western values were colliding with non-Western ones—in this case, with Chan Buddhist philosophy, which holds that everyday objects are not freighted with symbolism.

In an interview with Post, a website affiliated with the Museum of Modern Art, Huang once said, “I applied Chan Buddhism because I believed that the juxtaposition of Chan Buddhism and Dadaism would create new meanings, especially since I placed an Eastern element with a Western one—a term from intellectual history with one from art history.” According to Huang, both Dada and Chan Buddhist philosophy have in common an interest in “empty signifiers.”

The washed-out history work would become a preview of some of the provocations Huang would stage throughout his career. In later pieces, he made use of live animals and politically weighty objects, incurring the wrath of officials and activists alike. But Huang often said that he did not make art with the hope of getting into trouble. “First of all, I do not predetermine the work’s audience,” he told Ocula in 2018. “How can an artwork be created just to be censored? I am also against the idea of provocation for its own sake.”

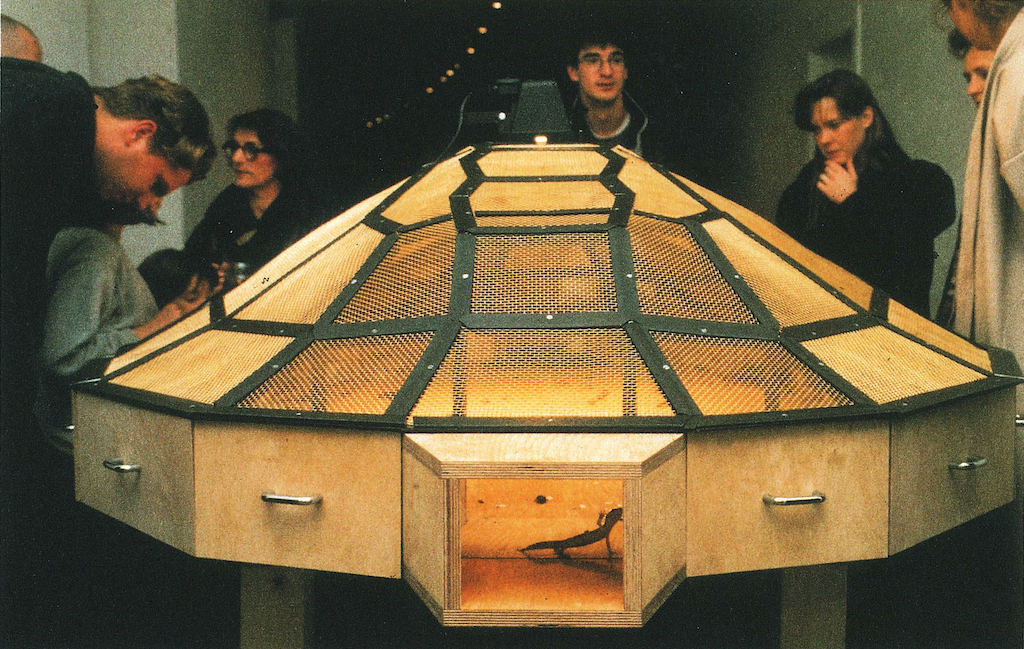

Huang was speaking on the occasion of one of the greatest controversies of his career—the exhibition of a piece to involve live insects, snakes, and lizards. That work, Theater of the World (1995), was included last year in a Guggenheim Museum Chinese art survey in New York that took its name from the Huang piece, and it was one of several works on view that involved animals. (The others were by Xu Bing and the duo Sun Yuan and Peng Yu.) In the Huang work, the animals were to prey on one another in a see-through case shaped like a tortoise shell.

Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the World, 1993, wood and metal structure with warming lamps, electric cable, insects (spiders, scorpions, crickets, cockroaches, black beetles, stick insects, centipedes), lizards, toads, and snakes.

©HUANG YONG PING/GUGGENHEIM ABU DHABI

After an outcry from animal-rights activists and a Change.org petition that was signed by thousands, the Guggenheim altered the work, presenting just its shell—without the animals. It was not the first time Theater of the World had drawn ire, but it was the most high-profile instance of controversy surrounding the work. Huang, who was traveling on an Air France plane when his piece was altered, responded by writing an essay on an air sickness bag that was then exhibited at the Guggenheim.

“[T]his work has repeatedly encountered ‘premature death’ without ever having a chance to ‘live,’” Huang wrote, adding, “An empty cage is not, by itself, reality. Reality is chaos inside calmness, violence under peace, and vice versa.”

The use of animals in the work was of a piece with Huang’s larger interest in comparing humans to beings that were lower on the food chain. His point was partly to create microcosms that paralleled the state of modern affairs today. For the installation Arche 2009, shown in 2009 at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Huang created a 50-foot-long paper boat filled with taxidermy animals that alluded to the story of Noah’s Ark. What may have at first glance seemed cute revealed itself as something darker—some of the the animals Huang included were disfigured or partly burned, and they alluded to a fire at Deyrolle, a Paris shop that had been a destination for natural history objects.

The bigger Huang’s installations got, the more feathers they tended to ruffle. Huang’s series “Bat Project” involved the exhibition of Lockheed plane fuselages that bear an almost exact likeness to an American spy craft that hit a Chinese fighter jet. (The spy plane was called a “bat,” but the animal is also a symbol of good fortune in China, lending the series’ title a layer of irony that’s typical of Huang’s work.) One work from the series was to go on view in an exhibition in the Chinese city of Shenzhen, much to the dismay of officials from China, France (which was co-sponsoring the show), and America. With the aim of patching over damaged diplomatic relations, the work was yanked before it even went on view.

Huang Yong Ping’s “Monumenta” commission at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2016.

JEREMY LEMPIN/EPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

“I still don’t know whether it was the Chinese or the French who put pressure on the organizers to suppress it,” Huang told the New Statesman America in 2008. “The US embassy sent people to take pictures of it, and asked the Chinese government to do an investigation. This was later retracted.”

That the work became ensnared in a global power play may have been Huang’s very intention. Huang was one of the most incisive artists dealing with the complex systems of power that guide international relations today—something he often observed from afar while working in Europe.

In 1989, at the age of 35, Huang went to Paris—and he would remain there for the rest of his career. His reasons for doing so were related to the state of China at the time: students were revolting against an oppressive regime, and it was potentially dangerous to be making art like Huang’s there. Huang was in the French capital to show his work at the the Centre Pompidou’s famed 1989 exhibition “Magiciens de la Terre,” which is regarded as one of the first major globalist art exhibitions in the West (it has also been controversial for the way it tokenized certain cultures). France went on to become an important part of Huang’s career—he went on to represent the country at the 1999 Venice Biennale in Italy, and in 2016 he was commissioned to the Grand Palais’s “Monumenta” commission in the French capital, one of the largest and most esteemed art projects in Paris.

While working in Paris, Huang continued to deal head-on with politics in China, in ways that were nuanced and rigorous. Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank, a 2000 sculpture originally shown at the Shanghai Biennale, is a 20-ton replica of the Pudong Development Bank. Many Western critics have pointed out that the structure will eventually fall apart, possibly referring to the instability of all institutions during the age of globalism. Huang in mind something different: a statement about the legacy of colonialism in China.

“Colonialism is closely linked to capitalism and the market, and banks are the fulcrums around which the market moves as the lever for China’s rapid development,” he said in the Ocula interview. “The 2000 Shanghai Biennale presentation was an allegory of that.”

Huang Yong Ping, Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank, 2000, installation view at Gladstone Gallery, New York, 2018.

DAVID REGEN/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GLADSTONE GALLERY

The spiky, unforgiving quality of Huang’s work differentiated the artist from a number of his colleagues, whose work has been more readily embraced by the market. During the 2000s, as prices for work by Chinese artists such as Yue Minjun began rising exponentially, Huang often spoke of how disinterested he was in the international market. According to a W magazine profile from 2009, Huang made François Pinault, one of the top collectors in France, wait years before allowing him to a buy a work on view at Pinault’s Punta della Dogana museum in Venice, and the artist turned down an offer to show at Pace Gallery’s then-newly opened Beijing space, citing a loyalty to Gladstone Gallery.

“Huang doesn’t give a damn,” Kamel Mennour, Huang’s Paris dealer, said in that profile. “Sometimes I’ll point out important clients to him, but it makes no difference. He never goes to openings or parties, never reads magazines. He wears the same pants and shoes every day. He’s just obsessively focused on his work.”

Huang Yong Ping was born in 1954 in Xiamen, China—a city that would become integral to his early work. While studying at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, Huang developed an interest in three areas that would inform the bulk of his work—the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, Zen Buddhism, and the art of Marcel Duchamp. He began by making paintings of industrial workers using spray paint—a boundary-pushing medium at the time—that would hint at the political leanings of his later work.

After graduating from art school, Huang returned to Xiamen, where he began working as a middle-school art teacher. Though Huang never saw the exhibition, a show of Robert Rauschenberg’s work at the National Art Museum in Beijing radicalized many of his colleagues. Rauschenberg’s famed fusions of art and life—the equalization of a mattress and a canvas, for example—offered new ways forward for Chinese artists, and Huang took up the artist’s mandate starting in the mid-1980s.

Huang Yong Ping, Colosseum, 2007.

DAVID REGEN/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GLADSTONE GALLERY, NEW YORK AND BRUSSELS

Working with his artist colleagues in the city, Huang formed a group called Xiamen Dada that staged prankish happenings as artworks. “Until art is destroyed, life is never peaceful,” Huang wrote in “Statement on Burning,” an essay that accompanied a piece in which he set fire to his paintings in front of the Cultural Palace of Xiamen. Another event held in this spirit involved Huang and his colleagues proposing an exhibition to the Fujian Art Museum, mounting it, and then, hours into its run, replacing all the works on view with found objects culled from the area surrounding the institution. (The show lasted about two hours before officials at the institution realized what the artists were up to, and shuttered it.)

It would be understandable to read Huang’s work as being overly conceptual, too caught up in its own beliefs about what is and isn’t art, were it not for the fact that the artist was deeply invested in rethinking how galleries and museums ought to function. In doing so, he laid waste to longstanding notions that the art world, both in China and far beyond it, should be separate from the rest of the world, and that Western artists worked in a zone that somehow existed outside the political demands of people around the globe.

One of Huang’s best and most forceful pieces is Towing Away the National Art Gallery (1988), a photo-collage in which the artist proposed a method for removing the facade of a Beijing art museum using hemp ropes. It was never realized, but the point, Huang believed, to have merely thought of ways of overthrowing the art system. “The museum is still there, unchanged, and I have never wanted to step inside it in 30 years,” he told Ocula. “Regarding rebellion or resistance, maybe these could be better understood in terms of Chinese phrenology: some people are born with a reverse bone—a sign of rebellion or resistance.”

[ad_2]

Source link