[ad_1]

A few months after the King of Pop faced his first public sexual abuse allegations, Vanity Fair reporter Maureen Orth wrote in January 1994 that “even by Hollywood standards, Michael Jackson’s weirdness is legendary, but he has always been protected by the armor of his celebrity.”

“Almost no one, especially those C.E.O.’s and moguls who make millions off him, has ever really questioned his motives: why this reclusive man-child with no known history of romantic relationships prefers to live a fantasy life in the company of children,” Orth wrote of Jackson, who later privately settled with accuser Jordan Chandler.

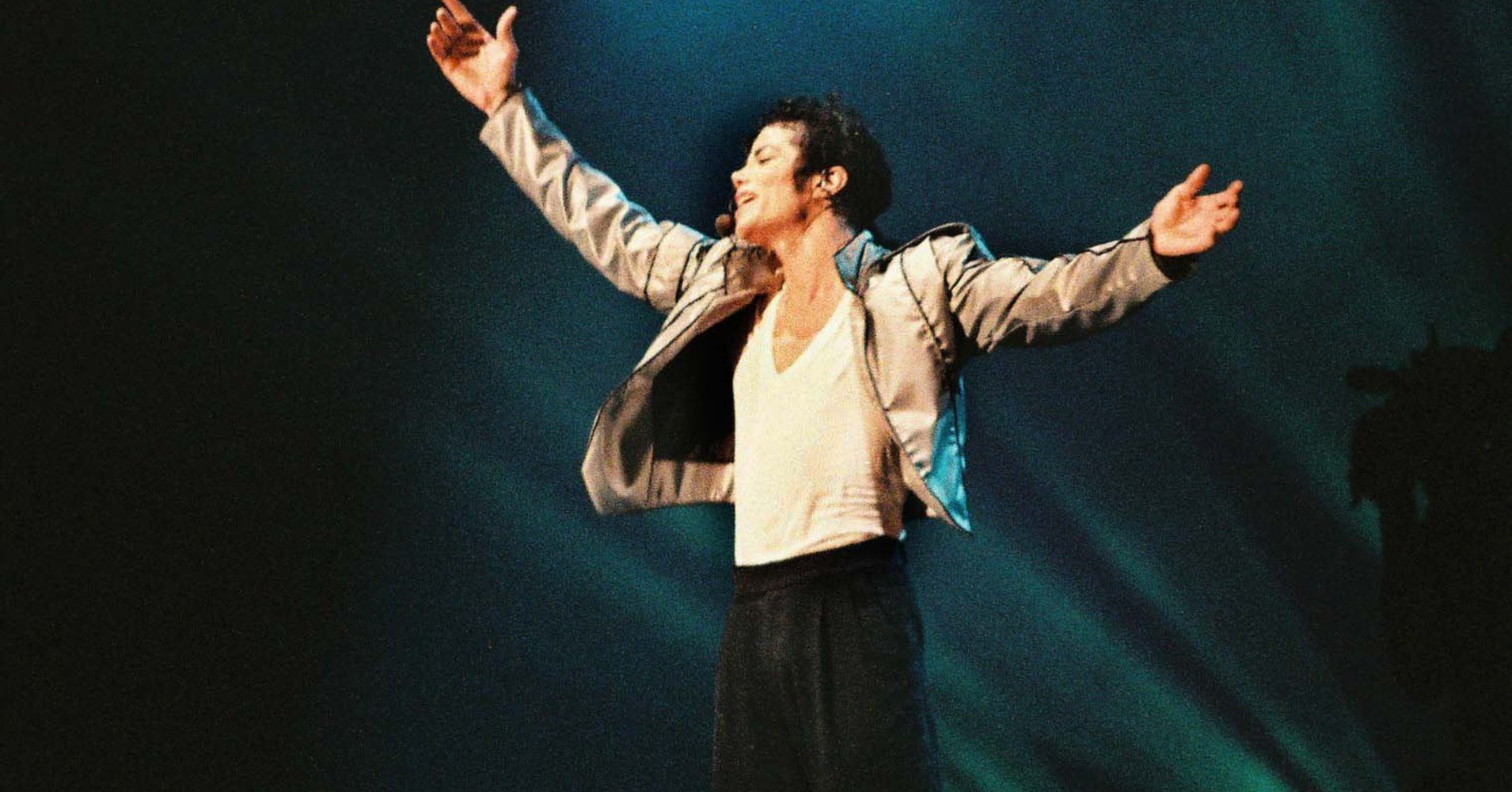

At its core, HBO’s “Leaving Neverland” is a devastating and searing excavation of how sexual abuse can tear apart the lives of accusers and their families. But particularly in its second half, airing Monday night, the documentary hints at how Jackson’s otherworldly superstardom enabled his alleged abuse to evade major scrutiny from the media during much of his career.

As with many sexual misconduct cases, media outlets faced the challenge of corroborating the allegations against Jackson. According to Orth’s 1994 article, some saw them as too salacious to cover.

Orth went on to detail how people often took their stories about Jackson to the tabloids because they would get paid by “the profitable and ever growing celebrity-gossip mill.” Reputable outlets such as The New York Times and Los Angeles Times didn’t extensively cover Chandler’s allegations in 1993, and when they did, they instead focused on the response from Jackson’s team, who claimed the singer had been extorted.

“A lot of people simply did not want to believe that Michael Jackson could molest little boys, and the tepid Establishment-press coverage reflected the public’s repugnance and ambivalence,” Orth wrote.

Jackson, who died in 2009, was the product of a machine of celebrity mythmaking, in which reporters, fans, and the people in his orbit ― including “Leaving Neverland” accusers Wade Robson and James Safechuck and their families ― became sometimes unwitting participants.

I love children and learn so much from being around them. I realize that many of our world’s problems today ― from the inner-city crime, to large-scale wars and terrorism, and our overcrowded prisons ― are a result of the fact that children have had their childhood stolen from them.

Michael Jackson, 1993

A look at media coverage of Jackson from the 1980s and early 1990s shows how that machine may have made it easier for the world to look the other way.

With the help of a savvy team of handlers who went after his critics, Jackson controlled his image.

Jackson, who denied the multiple abuse charges made during his lifetime and was acquitted after a 2005 trial, had plenty of defenders who thought the accusations were intended to take him down. A GQ cover story in 1994 opined over whether he had been “framed,” calling the coverage of the 1993 allegations “one of the nation’s worst episodes of media excess.”

Diane Dimond, a reporter for the TV tabloid show “Hard Copy,” broke the story on the initial allegations in 1993, but discovered sources close to Jackson had either been instructed not to talk or “wanted money.”

“They say, ‘I’d like to tell you something about Michael. He’s a dear sweet boy, and for $5,000 I’ll come on and tell you this.’ It absolutely has impeded me from presenting a full Jackson side of the story,” she said in 1994.

According to Vanity Fair, she received threats from Jackson’s representatives (which they denied). Dimond later wrote that fans attacked her outside her office, someone broke into her car on one occasion, and ”my office phone was tapped by Jackson’s private detective (confirmed to me by FBI sources),” she said in 2005.

Jackson contributed to his “squeaky-clean image” and universal appeal by giving few interviews and steering news reports toward his wide range of charity work involving children.

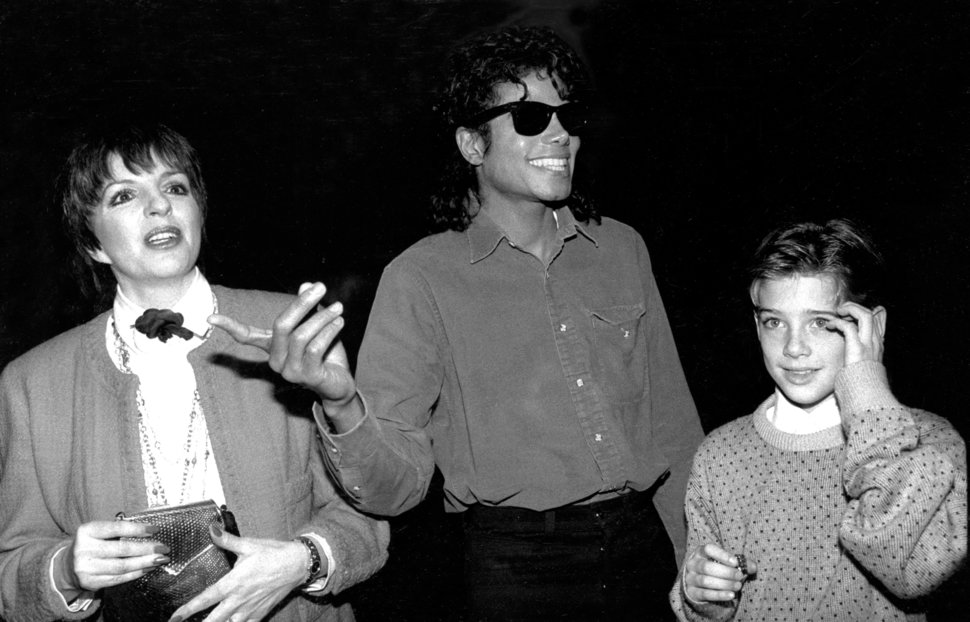

Jackson exerted power over his image and largely avoided interviews, as noted in a 1987 Rolling Stone profile that detailed “his control mania.” Director Steven Spielberg ― who cast Jackson as the narrator for the soundtrack to “E.T.” ― told the magazine in 1983 that the singer was “one of the last living innocents who is in complete control of his life.”

When Jackson did agree to the rare interview, it was often connected to his philanthropy and took on a sympathetic tone, like a 1992 Ebony magazine profile, which argued that Jackson had faced “a negative media campaign.”

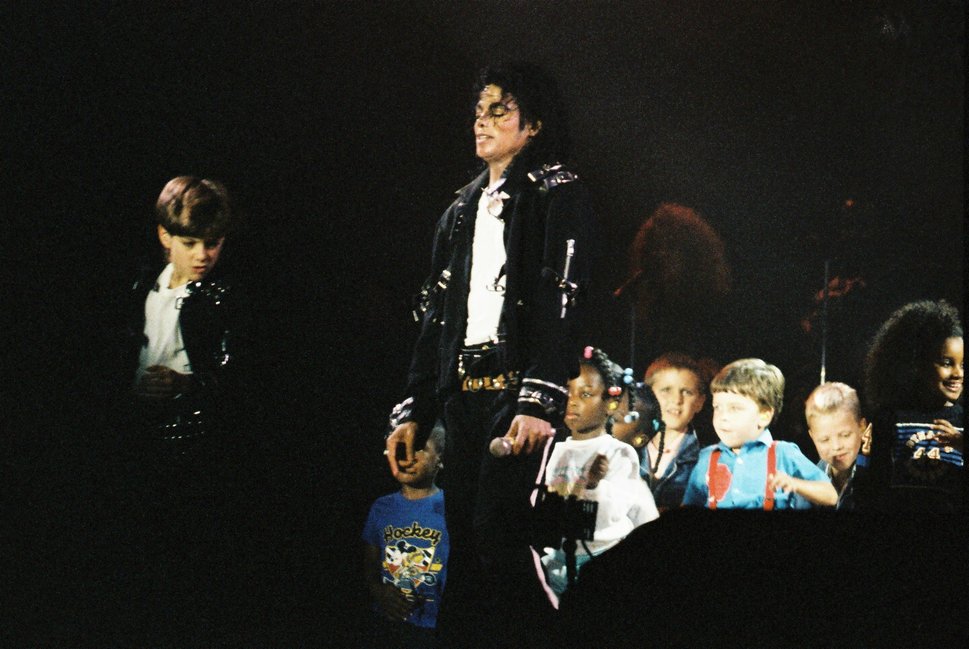

Many of the charitable initiatives that morphed his public image involved assisting sick children. Some were invited to spend time at his Neverland Ranch, where he hosted sleepovers — during which some of the alleged sexual abuse occurred.

“It’s part of my gift to make everybody happy, and to bring joy to everyone, especially children like this,” Jackson told Newsday in 1989, when meeting then 4-year-old leukemia patient Darian Pagan at a hospital in Brooklyn, New York. “My dream is to do a tour and see all the world’s children, all the hungry kids. Imagine that.”

Jackson often surrounded himself with children during his public appearances. During a 1985 PBS Newshour segment on Jackson’s famous Pepsi commercials, marketing analyst Faith Popcorn remarked on why children were among the singer’s biggest fans.

“All the young people emulate Michael Jackson in this country,” she said, according to a transcript of the segment. “And it must be every young boy’s fantasy to turn around and see Michael Jackson. I mean, how wonderful.”

Two years later, one of Jackson’s commercials starred then-9-year-old Safechuck turning around in amazement when seeing Jackson in his dressing room.

Profiles of Jackson often cast a tone of fascination and curiosity, writing off questionable behavior as mostly innocuous “personal oddities” or “eccentricities.”

News coverage in the 1980s and early 1990s often described Jackson as “child-like,” “wide-eyed,” “innocent,” an “enigma,” a “recluse” or a “Pied Piper.”

Certain stories made passing references to the sleepovers at Neverland and how many of his friends were children, details that look eerie now. A 1992 Rolling Stone feature described Jackson’s bizarre retreats for kids:

Jackson frequently has children over to play. According to his personal spokesperson, Bob Jones (who first worked with Jackson at Motown when the singer was a member of the Jackson 5), these regularly include “busloads” of underprivileged and terminally ill kids (such as the late Ryan White), as well as young personal friends of the superstar.

“When the children are here, sometimes they get so excited they just can’t go to sleep,” says Lee Tucker, who helped design Jackson’s movie theater and serves as his projectionist. “I’ll get a call at 2:00 a.m. sometimes: ‘Lee, can you show such-and-such movie?’ Neverland isn’t about kids going to sleep at a certain time. The kids really run the place when they’re here.”

In some news reports from that time, Robson was described as one of Jackson’s “young friends,” and Safechuck as his “new little friend.”

News coverage also emphasized how he liked being around children because he did not have his own childhood.

Jackson frequently told reporters that he felt most comfortable around children because he related to them more than he did with adults.

“They don’t wear masks,” he told Rolling Stone in 1983.

Similarly, the 1992 Rolling Stone profile noted:

Jackson is extremely fond of children. Those who know him believe that one reason he can relax with kids is that he truly believes they like him for himself, not because he’s a big star. As one associate observed, “If you’re under three feet tall, you can have complete access to Michael Jackson.”

He and his defenders often attributed some of his behavior to the fact that he had been famous his entire life and lived in a lonely bubble.

“With Michael, as with any superstar, reality and fantasy are totally confused,” John Landis, who directed Jackson’s “Thriller” music video, said in 1992. “It’s very difficult to remain sane.”

Also cited was his difficult childhood, including alleged physical abuse from his notoriously controlling father, which Jackson discussed at length with Oprah Winfrey in a 1993 live TV interview. But that defense is full of complications. As Slate’s Daniel Engber wrote this week, “the theory of intergenerational transmission of abuse” is a complex claim because “the science is filled with too many nuances and caveats to allow such a clear-cut explanation.”

These stories often referred to Jackson having dual images: one as an otherworldly superstar and unparalleled performer, the other as a tabloid fascination.

“I think he’s really Peter Pan,” his choreographer Michael Peters told the New York Times in 1984. “He is this constant dichotomy of man and child. He can run corporations and tell record companies what he wants, and then he can sit in a trailer and play Hearts for hours with a friend who is 12 years old.”

“As an entertainer he has no peer,” Rolling Stone wrote in 1987, while also noting that Jackson simultaneously was “the flighty-genius star-child, a celebrity virtually all his life, who dwells in a fairy-tale kingdom of fellow celebrities, animals, mannequins and cartoons … ”

Tabloid stories about “his plots to buy the Elephant Man’s remains, to oxygenate his body by sleeping in a hyperbaric chamber or to marry Elizabeth Taylor” further cemented that image.

While Jackson denounced these stories as “completely made up,” notably in the Oprah interview that was designed to rehabilitate his image, some reports suggest that the rumors (which led to the “Wacko Jacko” moniker in the tabloids) may have been planted by himself or his representatives.

In February of 1993, just weeks after the Oprah interview and months before Chandler made his allegations, Jackson was awarded the Grammy Legend Award. His acceptance speech now reads as a chilling summary of all of his different defenses promulgated over the years.

“I wasn’t aware that the world thought I was so weird and bizarre. But when you grow up as I did, in front of 100 million people since the age of 5, you are automatically different,” he said. “My childhood was completely taken away from me. There was no Christmas, there was no birthdays. It was not a normal childhood, no normal pleasures of childhood. Those were exchanged for hard work, struggle and pain.”

Jackson went on to thank “all the children of the world, including the sick and deprived.”

“I love children and learn so much from being around them,” he said. “I realize that many of our world’s problems today ― from the inner-city crime, to large-scale wars and terrorism, and our overcrowded prisons ― are a result of the fact that children have had their childhood stolen from them.”

Need help? Visit RAINN’s National Sexual Assault Online Hotline or the National Sexual Violence Resource Center’s website.

[ad_2]

Source link