[ad_1]

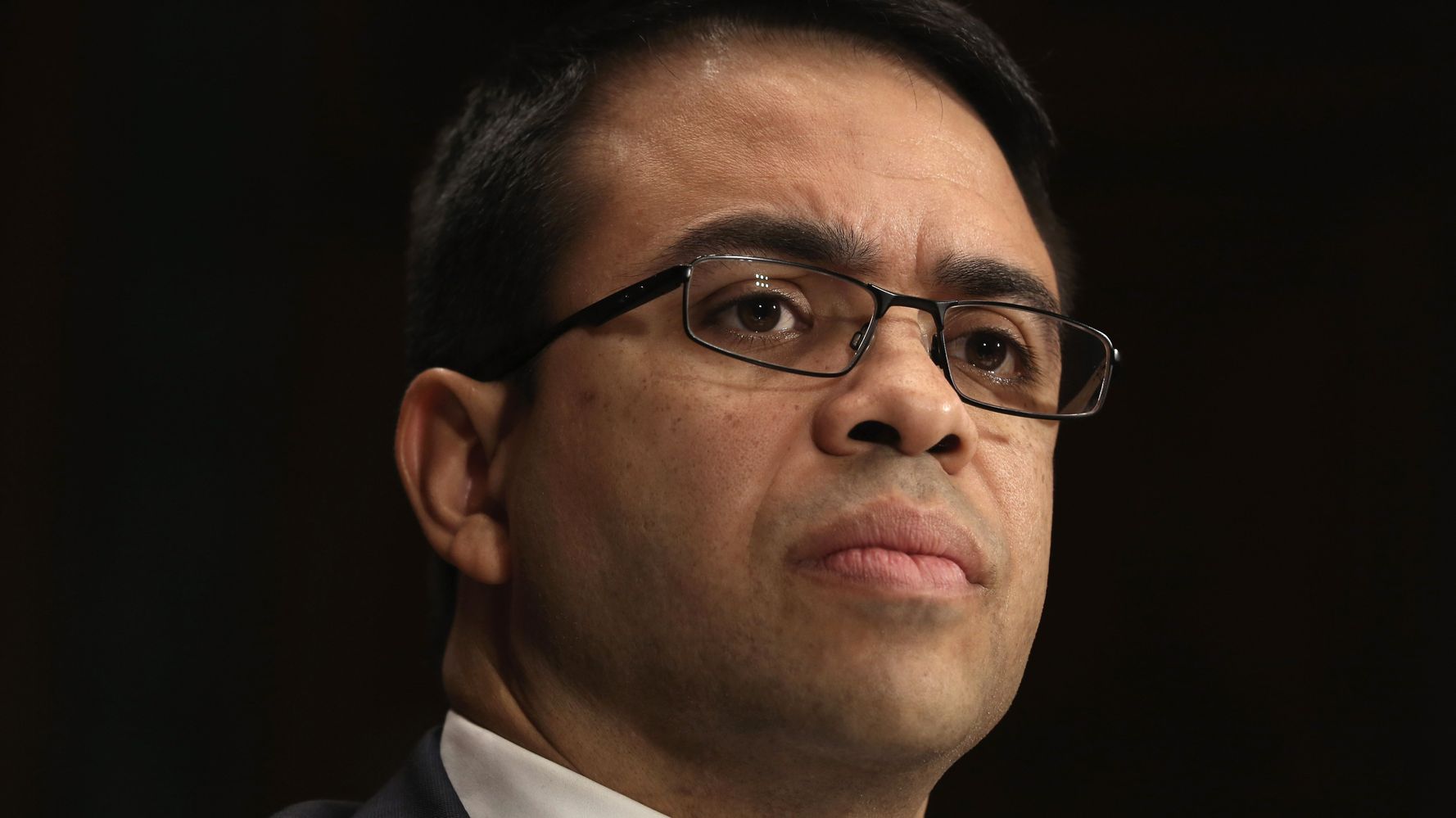

Debo Adegbile seemed like he’d make it through the Senate just fine. On Nov. 14, 2013, President Barack Obama nominated the 47-year-old lawyer to lead the civil rights division at the Department of Justice. No one questioned his qualifications: senior positions with the Senate Judiciary Committee and NAACP Legal Defense Fund, private practice, an expert in voting rights who twice defended the Voting Rights Act before the Supreme Court. And he had a reputation as a thoughtful lawyer, willing to listen to both sides.

Adegbile also had something else going for him. Democrats controlled the Senate, and they had just changed the rules so that presidential nominees needed only a majority of votes to be confirmed. In other words, it would be a lot easier for Obama’s picks to get through.

He should have been all set.

But in January 2014, the Fraternal Order of Police stepped in. The national law enforcement group made it its mission to take down Adegbile.

While at the LDF, Adegbile worked on an appeal for Mumia Abu-Jamal, one of the nation’s most famous death-row inmates, a former member of the Black Panthers who was convicted in the 1981 killing Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner.

Adegbile and the team of lawyers did not argue that Abu-Jamal was innocent. It was a constitutional case, the basis of which was that Abu-Jamal should receive a new sentencing hearing because the judge’s instructions to the jury had been flawed. In 2011, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit agreed. The Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, declined to review the circuit court’s decision and let the opinion stand.

Adegbile, who declined to provide a comment for this piece, never issued anti-police or anti-FOP statements. All he did was argue that Abu-Jamal deserved his constitutional right to a fair trial. But that didn’t stop FOP and Philadelphia law enforcement officials from portraying him as a radical who defended an “unrepentant cop killer.”

The message was clear: If you ever go against police unions, you will pay the price.

“FOP made him public enemy number one,” said a Democrat involved in the nomination process who, like some others interviewed for this piece, requested anonymity to speak freely.

Every single Republican voted against Adegbile. Seven Democrats did as well. Many were red state Democrats who were afraid that they’d be painted as anti-police in their reelection bids. Others felt local pressure. Adegbile’s nomination failed by three votes on March 5. He was the first nominee to fail under the Senate’s new rules.

The police unions “were absolutely the key reason for why certain Democrats felt like they couldn’t support the nomination,” said another Democrat who worked as a senior Senate staffer at the time.

“I think if you look into it, it would be a rare situation in which somebody was blocked from public service for having successfully vindicated the Constitution of the United States,” Adegbile told HuffPost after the vote in 2014.

The FOP and other police unions have been attracting significant attention in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd, a Black man who died after a police officer kneeled on his neck and ignored Floyd’s pleas for help. These groups have long resisted reforms, essentially adhering to the maxim, “If you give an inch, they’ll take a mile.”

Anti-racism protesters are trying to draw more attention to police union tactics. Some Democrats are discussing whether they should still seek the endorsements of police unions in their campaigns. Having the backing of law enforcement and being a “law and order” candidate is no longer a sure bet like it used to be.

“The FOP is quite powerful because of their purse strings, and also because of the politics of criminal justice, which makes many politicians afraid of the police and afraid to be on the bad side of police unions,” said Paul Butler, a Georgetown Law professor and author of the book “Chokehold: Policing Black Men.” “Now that politics is rapidly shifting, but in many cities across the country, if the police are against you, that’s a death knell for a politician.”

But the FOP is extremely savvy. The Adegbile nomination is a case study of how it wields its power on Capitol Hill. It operates much like the National Rifle Association, taking extreme positions and using its influence ― or perceived influence ― to frighten lawmakers into voting in its interests.

“In a democratic process, when you allow a powerful special interest to veto the people charged with oversight, you’ve already given yourself away to corruption on some level,” said a person involved in the confirmation process. “What you’re trying to do is you’re trying to disarm the laws that Congress has enacted for the express purpose of managing that industry and entity and enforcing federal law. It’s egregious everywhere. It’s particularly egregious when the area is civil rights.”

National Smear Campaign

The FOP is the nation’s largest police association, with over 330,000 members. The group marshals support with its approximately 2,000 chapters all over the country ― some are unions and some are simply fraternal organizations.

In Washington, the face of the FOP is Jim Pasco, the group’s executive director. He’s known as a highly effective and tenacious lobbyist who has cultivated relationships on both sides of the aisle. FOP has spent $220,000 a year lobbying since 2007, but its influence goes far beyond the relatively low dollar amount.

Robert Driscoll, a former deputy assistant attorney general in President George W. Bush’s administration, said that as soon as he saw FOP jump into the Adegbile fight, he knew which way it was going to go.

“This guy’s not getting confirmed,” he told Politico in 2015. ”And even when it looked like he was going to get confirmed, I still said I didn’t think he’d get confirmed.”

In response, Pasco said that indeed, FOP had planned to “fight this guy until the last dog died.”

The FOP did not return requests for comment for this piece.

On Jan. 6, 2014, FOP President Chuck Canterbury threw down the gauntlet with Obama, writing a letter saying that Adegbile ”turned the justice system on its head” with his defense of Abu-Jamal.

“We are aware of the tried and true shield behind which activists of Adegbile’s ilk are wont to hide — that everyone is entitled to a defense; but surely you would agree that a defense should not be based upon falsely disparaging and savaging the good name and reputation of a lifeless police officer. Certainly any legal scholar can see the injustice and absence of ethics in this cynical race-baiting approach to our legal system,” Canterbury wrote.

That opposition was critical in providing cover for senators to vote against Adegbile. Republican Sens. Jeff Flake, Charles Grassley and Rob Portman, among others, all cited FOP’s position in their statements against Adegbile.

“The national Fraternal Order of Police has made it abundantly clear ― this is a significant vote in their mind,” Rep. Mike Fitzpatrick (R-Pa.), a leading voice against the nomination, said in a Fox News interview at the time. “Either you’re with the police officers in this case or you’re against them.”

Fox News gladly took up the cause of blocking Adegbile’s nomination with regular segments.

On Jan. 8, 2014, Maureen Faulkner, the widow of Daniel Faulkner, went on Megyn Kelly’s show and said that Obama nominating Adegbile was “like spitting on all of our officers and our federal agents throughout America.”

“Why did [Obama] not come to some other outlet — the National Fraternal Order of Police or other outlets — and say, ‘Let’s do background work on him?’” she wondered.

The main way critics tried to smear Adegbile was by portraying him as a radical: He was a radical nominee, pushed by a radical president. The idea that Adegbile would defend an unpopular figure on constitutional grounds ― to ensure a fair trial ― was disqualifying, according to Republicans.

On Sean Hannity’s Jan. 8 show, Fox contributor Katie Pavlich said Obama may have wanted to nominate him “because he has a very racial past and a racial history of pushing racial politics through actions inside the law.”

Fitzpatrick went even further, saying that Adegbile and other civil rights lawyers were simply trying to profit off the police officer’s death with a ”shameless ‘cottage industry’ of money and promotion has arisen from Jamal’s heinous act which continues to torture Officer Faulkner’s widow and family.”

No one was ever able to point to a single disparaging comment that Adegbile himself ever made about Faulkner. In 2009, the LDF filed an amicus brief in favor of Abu-Jamal’s appeal, arguing that there had been racial bias in the jury selection process. He lost that round. But two years later, LDF represented him in court and successfully argued that the jury instructions were improper during the trial that sentenced him to death.

Racial overtones ― and outright racism ― were part of the smear campaign against Adegbile. The Washington Times ran a particularly vile cartoon, where Adegbile was holding up a sign saying “cop killer.” It played off Adegbile’s childhood job as an actor on “Sesame Street” and used racist iconography to stereotype the nominee, who is the son of a Nigerian father and an Irish mother. His mother, who struggled with poverty and even homelessness, raised Adegbile on her own.

Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) was a key FOP ally in the fight. In The Philadelphia Inquirer’s examination of the successful effort to tank Adegbile, Toomey’s office shared some of its extensive research on the Abu-Jamal case that it used as proof of Adegbile’s unfitness for the Justice Department job.

“None of the information they provided cited direct comments or actions by Adegbile,” the paper reported. But Toomey’s office said that Adegbile was responsible for all the public comments his team members made. In another instance, it used what appeared to be an inaccurate news report to argue that LDF lawyers were trying to get Abu-Jamal out of prison ― rather than the fact that they were actually just working on re-sentencing.

Toomey wrote an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal with Seth Williams, the district attorney of Philadelphia, outlining the opposition to Adegbile. It’s not surprising that Williams didn’t like Adegbile’s involvement with Abu-Jamal: Williams was the losing lawyer in that case, and unsuccessfully tried to get the Supreme Court to take it up. That fact was never directly mentioned in the piece.

Three years later, Williams went to prison on public corruption charges.

While conservatives and FOP opposed Adegbile, he had the wide support of civil rights organizations. Eighty-six groups wrote a letter calling him “one of the preeminent civil rights litigators of his generation” and “a consensus builder.”

And as many Adegbile supporters pointed out, other prominent people had defended people who had committed horrible crimes. Roberts, for example, defended a man who murdered eight people ― and he was sitting on the Supreme Court.

Then-Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) referenced Roberts in a fiery floor speech after Adegbile’s nomination failed. He made clear that he believed that if Adegbile were white, he would have been confirmed:

If you are a young white person and you go to work for a law firm … and that law firm assigns you to a pro bono case to defend someone who killed eight people in cold blood … my advice from this, what happened today, is you should do that … Because if you do that, who knows? You might wind up to be the chief justice of the United States Supreme Court.

However, if you are a young Black person and you go to work for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund … and you’re asked to sign an appeal for someone convicted of murder, what the message said today is, ‘Don’t do it! Don’t do it.’ Because you know what? If you do that, in keeping with your legal obligations and your profession, you will be denied by the U.S. Senate from being an attorney in the U.S. Department of Justice.

At his hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Jan. 9, 2014, Adegbile defended himself, acknowledging the pain that Faulkner’s family no doubt felt.

“It is a tremendous loss to lose a civil servant, a public law enforcement officer serving the people, and I would never personally or professionally say anything negative about that horrific loss,” he said. “My sympathy goes to his family, to the community in Philadelphia and it would be completely contrary to my person to make any negative comment about that particular situation.”

He added that death penalty cases were “the hardest cases.”

“But our commitment in the Constitution is to follow our procedural rules even in those hardest cases, perhaps especially in those hardest cases, so that all of our rights can be vindicated,” Adegbile said. “But I completely understand how difficult these cases are.”

Democrats Fear Police Union Backlash

Nominees to lead the civil rights division at the Justice Department are often controversial. But the Obama administration seemed unprepared for just how tough the Adegbile fight was going to get.

Seven Democrats ultimately voted against Adegbile: Bob Casey (Pa.), Chris Coons (Del.), Joe Donnelly (Ind.), Heidi Heitkamp (N.D.), Joe Manchin (W.Va.), Mark Pryor (Ark.) and John Walsh (Mont.).

Casey was an early and perhaps unsurprising Democratic senator to say he was going to oppose Adegbile. Not only does he represent Pennsylvania and fit within the more moderate and conservative wing of the party, he faced intense pressure at home from police officers, constituents and Faulkner herself to vote no.

“After carefully considering this nomination and having met with both Mr. Adegbile as well as the Fraternal Order of Police, I will not vote to confirm the nominee,” he said in a statement, citing the “open wounds for Maureen Faulkner and her family as well as the City of Philadelphia.”

Even liberal Democrats recognized the politically fraught atmosphere around Adegbile. When Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) met with Adegbile, he told Adegbile that it was going to be a tough vote, according to someone who attended the meeting. Whitehouse later voted in favor of Adegbile’s nomination.

It’s common for high-profile nominees to go around and meet with senators. Some who came out against Adegbile gave no indication of how they were going to vote during those meetings. Pryor peppered him with questions about the law and quizzed him about legal precedent, but never said he was going to vote no, as he eventually did.

Heitkamp was more direct. She told Adegbile that he was qualified and an excellent candidate but politically, she couldn’t vote for him. She was gearing up to take some other controversial votes and needed political cover.

“It wasn’t the outcome we’d have wanted, but in a way, we were grateful that Sen. Heitkamp was so straight with us when we met with her. We didn’t get that candor ― maybe even honesty ― from every member of the Democratic caucus,” said Elliot Williams, a principal at The Raben Group who was deputy assistant attorney general for legislative affairs at the Justice Department at the time. He attended many of the Senate meetings with Adegbile.

Heitkamp didn’t return a request for comment for this piece, but after the vote, she told constituents in North Dakota that if Adegbile had been confirmed, “there would have been three years of discussions about the Jamal case … and not civil rights.”

She also said his nomination was the equivalent of naming a tobacco executive to the top health agency: “I’m pretty sure that if George W. Bush had nominated someone who had been chief counsel of Phillip Morris to be the chief counsel for HHS there might have been some discussion on the other side.”

By far the biggest surprise vote against Adebile was Delaware’s Chris Coons. Coons cared about civil rights and, as a graduate of Yale Law School, people expected that he understood the constitutional importance of ensuring a fair trial for all ― even with unpopular figures like Abu-Jamal. He voted for Adegbile to pass out of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

But Coons is also co-founder of the Law Enforcement Caucus, and part of Delaware is in the Philadelphia metro area. So he also felt pressure from back home ― not just from law enforcement ― to oppose Adegbile. And in his statement announcing his no vote, he specifically said that he could not back him because law enforcement didn’t like him.

″[A]t a time when the Civil Rights Division urgently needs better relations with the law enforcement community, I was troubled by the idea of voting for an Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights who would face such visceral opposition from law enforcement on his first day on the job,” Coons said.

It was the right thing to do. I am not proud of every vote I’ve cast, but I am proud of that one.

Former Sen. Mary Landrieu, on her vote for Adegbile’s confirmation

The Obama administration didn’t seem entirely prepared for the onslaught that Adegbile faced, according to people who worked on the nomination. Yet as the danger became apparent, administration officials did what they could to try to save him. The president personally appealed to Senate Democrats at a caucus meeting and called individual members.

Even on the last day before voting, Vice President Joe Biden, Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) were on the phone trying to sway senators. Biden was particularly key. He had a long history of working with police unions, was close to Casey, and from Coons’ state. He also was ready to break a tie in the Senate if the vote ended up being that close.

Coon’s vote was a shock and deep disappointment to many members of his party, as well as to many of his constituents. (Notably, Delaware’s other Democratic senator, Tom Carper, voted for Adegbile.) It also hurt his credibility on civil rights issues, even though he had ― and still has ― a high score from groups like the NAACP and the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. Coons seemed to quickly realize he had made a mistake.

“I think the black community had so much higher hopes for Sen. Coons on civil rights, but it seems like he is not a civil rights person,” Delaware NAACP President Richard Smith told Gannett in an article published March 7, 2014.

In the months following the Adegbile matter, Coons met with members of the Black, faith, and legal communities in Delaware to help repair the damage and apologize for his vote. According to Smith, Coons promised to support Adegbile if he were renominated.

A group of more than 200 students, faculty and alumni of Yale Law School and Yale Divinity School also wrote a letter to the senator, saying his vote sent a ”disturbing message” to young people who want to go into public service.

And Coons has continued to hear about it, even six years later.

The progressive judicial group Demand Justice has been running ads against Coons in Delaware, hitting him for voting for some of President Donald Trump’s judicial nominees. One of the ads also goes after him for his vote against Adegbile. Coons is up for reelection this year.

Coons spokesman Sean Coit responded that the senator “is one of the most effective and persistent questioners on the Judiciary Committee, where he regularly presses President Trump’s judicial nominees and Justice Department leadership on their civil rights records and their commitment to living up to the promises of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Coons told HuffPost this month that he has had lengthy conversations with people in his community over the years about that vote.

“I have expressed regret both for the process that got me to that vote and that specific vote … I was ascribing to Debo Adegbile some of the consequences of the actions of a client of his. As a matter of law, that’s not right,” he said. “But part of what was going on, I was from the Philadelphia suburbs, and that particular case produced a lot of very intense feelings in the law enforcement community.”

Pryor also reached out to Adegbile the day after the vote, although it’s not clear what was discussed.

Obama appointed Adegbile to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 2016, where he still serves today.

“The Senate rejected him in this totally historic ― and I mean bad historic ― moment,” said another Democrat who was a senior Senate aide at the time. “And he has just kept on. That really speaks to the dedication that he has, the character that he has and the bravery that he has in a way that the senators ― several of whom are no longer in the Senate, it should be noted ― do not have.”

It doesn’t seem that the Adegbile vote really had much effect on senators one way or the other, despite the political calculations that clearly went into the decision on which way to vote. Pryor lost his reelection bid that November. Walsh, another “no” vote, dropped his reelection bid that year after a plagiarism scandal. Heitkamp and Donnelly lost their races in 2018.

“Let’s not kid ourselves. The senators weren’t taking a moral stand here. It was a political one,” Elliot Williams said. “But look: Pryor lost his next election by 17 points. Heitkamp lost hers by 11. It’s hard to see how this vote on someone they all agreed was singularly qualified really changed anything for anyone politically.”

Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-La.) was also in a tough reelection race that year ― which she ended up losing ― but she took a different path and voted for Adegbile.

“It was the right thing to do,” she told HuffPost. “I am not proud of every vote I’ve cast, but I am proud of that one.”

Landrieu’s situation was also a bit different than that of the senators from, say, West Virginia and Montana. Her state is more than 30% Black, and Landrieu said considering the concerns of those communities was an important part of job.

“I think my record reflects support for the military and police, but this was so clear-cut, and this guy was just maligned for no reason. It wasn’t a difficult call for me,” she said.

Manchin, one of the only three Senate “no” votes remaining in office, didn’t seem to remember the Adegbile vote when asked about it in the Capitol by HuffPost recently.

Casey said in a statement this month that he still believes he did the right thing: “Reasonable people disagree with my vote against Mr. Adegbile’s nomination. While I respect their viewpoint, and struggled with this decision back in 2014, I stand by it.”

Leahy is actually one of FOP’s closest allies on Capitol Hill ― its ”foremost champion” in Congress ― working with the group most notably on issues around officer safety. But they don’t always see eye to eye, especially on civil liberties and civil rights matters. And in this case, there was no way the senator was going to budge. Adegbile was a staffer for Leahy on the Senate Judiciary Committee, and getting him confirmed was deeply important to the senator.

The effect of the FOP in Adegbile’s defeat was not lost on senators. Pasco explicitly said it would use how senators voted on the nomination when FOP was considering which candidates to support in the future.

“Was it your sense, among your colleagues, that the threat of any backlash or retaliation from law enforcement unions was a factor?” NPR asked Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) in an interview in March 2014.

“Yes, it was,” he replied.

On March 5, Reid and Leahy had to finally admit that they didn’t have the votes to push Adegbile through. And they had to break the news to him.

Both men were fond of Adegbile and outraged at how he had been treated. Reid told him that he could pull the nomination if Adegbile didn’t want to go through the spectacle of having it fail, according to multiple people familiar with the conversation.

That scenario was what some senators, such as Coons, were hoping for. (Coons’ office would not comment on this point.) It would spare them from having to take a tough vote. But Adegbile was the one who personally insisted that it should go forward.

“He said, ‘I’m 47 years old. … I’ve spent all my life trying to do the right thing,’” Reid said the day after the vote, referring to his conversation with Adegbile. “’I didn’t step into a courtroom for this man. I didn’t write a word for the briefs for this man. … I’ve done nothing wrong. I think if I’m going to be voted down, it’s a good time to start a discussion on civil rights in America.’”

‘Enormous Race Issues’ In Police Unions

Police unions are not like other unions. They have long occupied an uneasy place in the labor movement, with their collective bargaining agreements often undermining accountability over shootings and protecting cops with long histories of brutality and disciplinary issues. Many people are now questioning whether police unions should have their power curtailed ― or be abolished altogether.

Comments by some of their members and leaders haven’t helped the perception that they stand in the way of reform and protect their members at the expense of social justice and civil rights.

The Miami FOP pledged $100,000 for the legal defense fund for the police officer charged with murdering Rayshard Brooks, a Black man in Atlanta whose death at the hands of police was caught on video. A Florida FOP chapter posted on Facebook saying that it wanted to hire police officers in Buffalo, New York, and Atlanta who have been charged with misconduct in violent incidents with protesters.

What FOP chapters are doing now isn’t any different from what they’ve done in the past by defending and raising money for officers who shoot Black people. In 2012, the president of the Miami FOP, Lt. Javier Ortiz, defended the cops in Cleveland who fatally shot Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy who had been playing with a toy gun.

“Act like a thug and you’ll be treated like one,” Ortiz wrote on Twitter.

Butler, the author and law professor, said the rhetoric of FOP officials is “just frequently racist.”

“There’s no other way to describe it,” he said.

“I think police unions have enormous race issues,” added Roy Austin, who was deputy assistant attorney general in the civil rights division under Obama. “I think that’s why you see their leadership being almost exclusively white male. … They are organizations that push back on all accountability in very harsh terms. They are organizations that are not afraid to engage in dog whistles and even more blatant forms of race-baiting against elected officials who they don’t like.”

The unions have been extremely cozy with the Trump administration, far different from how they behaved when Obama was in office, a period in which the head of the National Association of Police Organizations ― which also opposed Adegbile ― said Obama was waging a ”war on cops.” In 2016, the president of the Illinois FOP said Obama had ”done little to correct” the notion that “it is OK to demonize and urge violence against police officers.”

“The FOP was a bad actor throughout Obama’s eight years in office,” a former Obama administration official said. “President Obama is as thoughtful as anyone when it comes to how complex and difficult this issue is, but we found the FOP to be a large part of the problem, not the solution. They didn’t engage in good faith, and much like Donald Trump, refused to acknowledge what was plain as day to everyone else. If you’re not going to be honest about the realities, you’re not going to be able to get much done.”

“We made decent progress on policing when Obama was in office, but if we had willing partners in the FOP, we could have done so much more,” the official added.

What’s been consistent is the FOP and other police unions standing in the way of racial justice, standing in the way of police accountability and transparency.

Paul Butler, author of “Chokehold: Policing Black Men”

The FOP was particularly incensed that the Obama administration was undertaking “pattern-or-practice” investigations of police forces, looking at systemic issues rather than a few bad actors. The government can sue over “a pattern or practice of conduct … that deprives persons of rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States.” Often, instead of going to trial, the police department will agree to make reforms under what’s known as a “consent decree.”

In his letter to Obama opposing Adegbile, FOP President Canterbury criticized Tom Perez, the outgoing head of the civil rights division at the Justice Department, and Austin, his deputy, for taking an “aggressive and punitive approach towards local law enforcement agencies.”

The Obama administration was considering nominating Austin to be director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement around the same time of the Adegbile controversy, according to a person familiar with the matter. But Austin’s name was never submitted after FOP made clear it would fight tooth and nail against him. (Austin declined to comment on whether he was ever up for the position.)

The Trump administration, meanwhile, has given the FOP most of what it has wanted ― including the reversal or deprioritization of reforms passed during Obama’s time in the White House. And in 2017, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions gave a keynote address at the FOP annual convention and announced a giant gift: a resumption of a program that would give police forces surplus military equipment.

“We have your back and you have our thanks,” Sessions said, announcing the executive order that Trump later signed. The Obama administration had curbed the scope of the program, which was started in 1990.

But law enforcement isn’t a monolith, and not all police officers are happy with what FOP has done.

When the national FOP endorsed Trump in 2016, organizations representing Black officers spoke out in disagreement.

The Philadelphia Guardian Civic League, a group that represented 2,500 Black officers in the city, objected to the endorsement and had previously called Trump an ”outrageous bigot.”

“Is this endorsement a result of the surveying of the membership of individual unions that represent police officers or is this endorsement the result of a few individuals who may stand to benefit from a so-called law and order candidate who knows nothing about the criminal justice system and is opposed to basic reforms of the system?” asked a statement from Blacks in Law Enforcement of America.

Though its leadership is overwhelmingly white, FOP claims that 30% of its membership is officers of color.

The National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, unlike the FOP, has called for reforms after high-profile shootings by police. The group also endorsed Adegbile’s Justice Department nomination.

A number of other law enforcement organizations and police chiefs condemned Trump when he urged police officers not to be “too nice” with suspects in a 2017 speech, while the FOP simply said, “The president’s off the cuff comments on policing are sometimes taken all too literally by the media and professional police critics.”

By aligning itself so closely with Trump, the FOP risks further alienating Democrats who may already be skeptical.

The FOP is currently involved in discussions with members of Congress on both sides of the aisle over legislation to reform policing. Police leaders have said they’re open to establishing national standards ― including possibly banning chokeholds ― and Rep. Karen Bass (Calif.), the chair of the Congressional Black Caucus who is leading Democratic efforts ― said she recently met with FOP officials for an hour.

But FOP leadership has already come out against some bigger measures, such as establishing a national database tracking police officers who have been terminated, and ending qualified immunity ― a practice that makes it nearly impossible to sue police officers for wrongdoing.

Butler also expressed skepticism about how much the group will change.

“This is a kind of singular moment in which the politics are changing, but it could be singular in the sense that it’s also temporary ― and that when these dramatic or egregious cases of police violence against Black men aren’t on the front page every day, then the politics will revert back,” he said.

“And to the extent that this moment of reform comes and goes ― as other moments of reform have come and gone ― what’s been consistent is the FOP and other police unions standing in the way of racial justice, standing in the way of police accountability and transparency,” he added.

But Democratic politicians are increasingly having conversations and giving second thoughts about how reflexively they want to be seen as being on the side of law enforcement. And it seems possible that FOP’s tactics are getting more attention, with more people aware of the need for a strong government regulator looking out for civil rights.

After all, the first major challenge that came up for the civil rights division at the Department of Justice after Adegbile’s nomination failed was the case of Michael Brown, an 18-year-old Black man shot by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

Igor Bobic contributed reporting.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link