[ad_1]

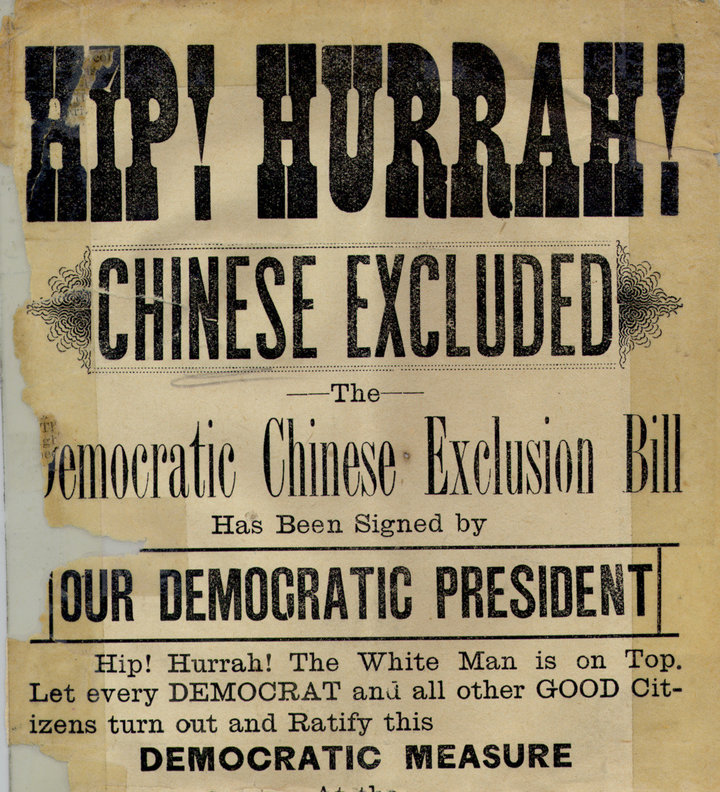

WASHINGTON ― In 1882, Congress voted to ban an entire ethnic group from immigrating to the United States.

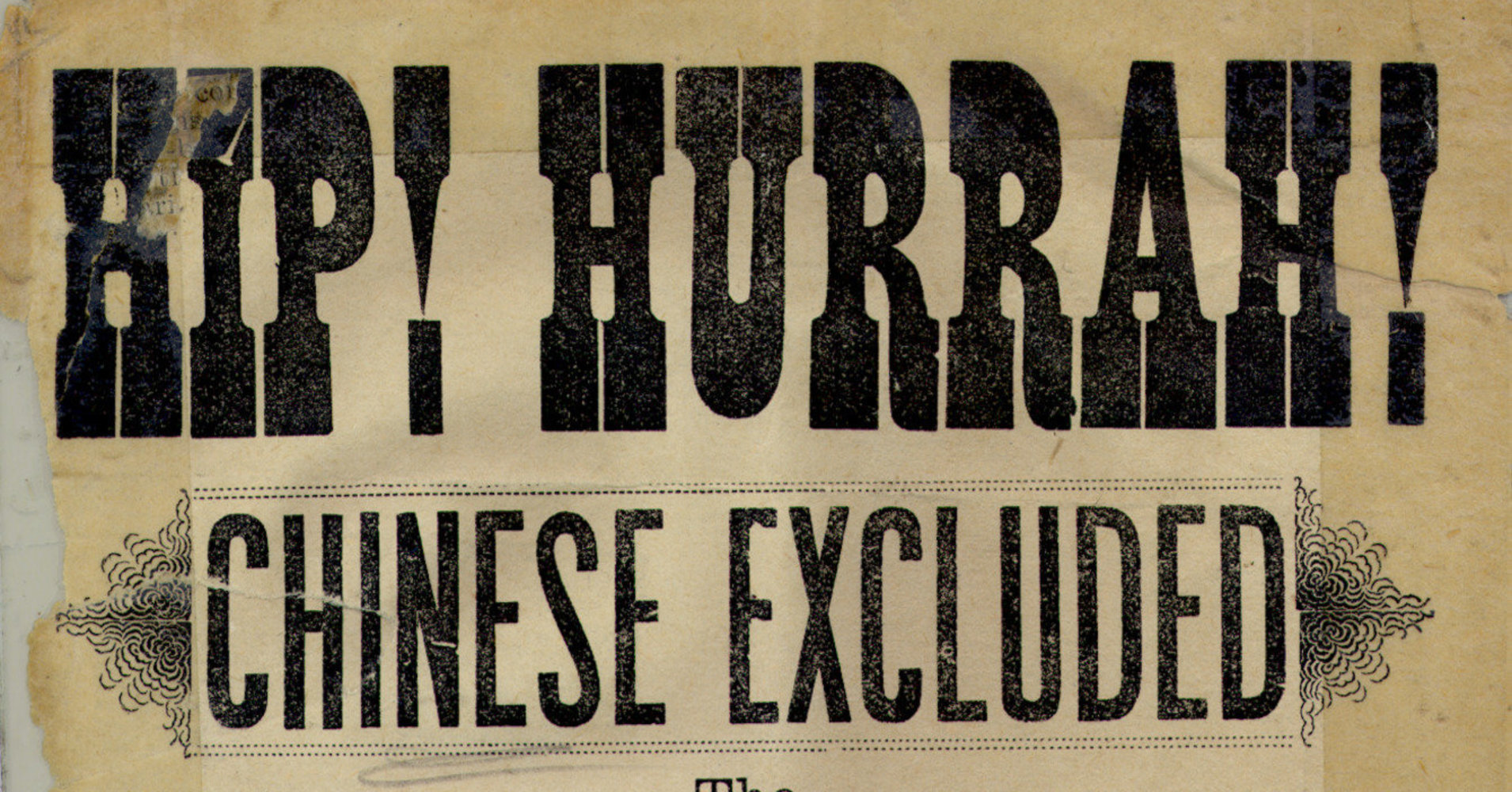

The Chinese Exclusion Act, iterations of which remained on the books for over 60 years, had a lasting effect on the history of U.S. immigration, as depicted in a new PBS documentary airing Tuesday.

Filmmakers Ric Burns (brother of Ken) and Li-Shin Yu trace not only the law’s development and implementation but also its connection to other integral parts of American history unfolding contemporaneously, like segregation in the Jim Crow South, urbanization on the East and West Coasts, and trade abroad.

At a screening of the film last week, Burns called the Chinese Exclusion Act a “quintessentially American story” and described it as “the biggest part of American history that people don’t know about,” because you would be hard-pressed to find it mentioned in many history courses.

If you want to know about immigration in America and you don’t know the story of Chinese exclusion, it would be like saying you want to know about race relations in America, but you’ve never heard of slavery.”

Filmmaker Ric Burns

In the film, several historians marvel that some Americans are shocked to learn about the Chinese Exclusion Act.

“Many Americans today cannot believe this happened. How could this country, with its culture, with its politics, with its economics, do what it did against a whole class of people?” NYU professor John Kuo Wei Tchen says.

But while watching the documentary amid today’s political climate, it isn’t unbelievable at all. Burns and Yu acknowledged that it doesn’t take much effort to see parallels to President Donald Trump’s America — though this was not their original intention, as they began working on the film six years ago, Burns said.

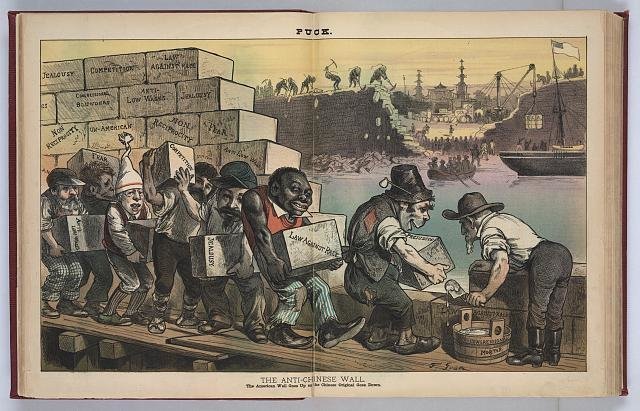

Central to the bill’s 1882 passage were political attacks on Chinese immigrants that labeled them “unassimilable” and portrayed them as economic threats to white Americans and a filthy scourge on society. The film shows how newspaper headlines and editorial cartoons from that period disseminated this propaganda.

Nineteenth-century politicians’ nativism and fear-mongering are remarkably similar to today’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. President Donald Trump famously began his presidential campaign by saying that Mexico was sending rapists, drug dealers, and criminals to the U.S.

Other right-wing political figures have raised the old complaint that certain immigrants are unassimilable. During an NPR interview earlier this month, Trump’s chief of staff, John Kelly, said that undocumented immigrants are “not people that would easily assimilate” and “don’t integrate well” — an uncanny reminder of how this political language persists.

Burns sees another commonality in the rhetoric: the “factless nature” of claims that immigrants are stealing our jobs.

“Both then and now, there’s zero truth to it,” he said. “These things almost never have any basis in reality. It becomes a function of playing to fears, playing to usually white vulnerabilities, and finding wedge issues for politicians.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act tells us all we need to know not just about immigration, but about the story of America.

These parallels make it particularly difficult and infuriating to watch the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act unfold in the film, including how it raised questions about birthright citizenship that were later settled in an 1898 Supreme Court case.

Trump is among those who have relitigated the issue in the decades since: During his presidential campaign, he suggested abolishing birthright citizenship.

There are also echoes of the Chinese Exclusion Act in the legal battle over Trump’s travel ban, which bars people largely from majority-Muslim countries from entering the U.S. It’s yet another compelling piece of evidence for the film’s central argument: The Chinese Exclusion Act tells us all we need to know not just about immigration, but about the story of America.

The events of the film intersect with another grim period of American history: the Jim Crow era in the South. According to the film, the California politicians spearheading discrimination against Chinese immigrants built support for the exclusion act by compromising with Southern politicians trying to pass measures to systematically disenfranchise black people. The political maneuvering, which Burns referred to as “horse-trading,” essentially amounted to exchanging one form of discrimination for another.

Sexism and misogyny also fueled the fire. Laws that helped lay the foundation for the 1882 bill were particularly discriminatory against Chinese women, who were stereotyped as prostitutes. As Columbia University historian Mae Ngai relates in the film, Chinese women were required to prove they were not prostitutes to be admitted to the U.S, a process so stringent that it effectively discouraged most women from immigrating.

Through these connections, the documentary effectively makes the case that the Chinese Exclusion Act is fundamental to questions of American identity.

“It is not a melodramatic or breathlessly hyperbolic thing to say that if you want to know about immigration in America and you don’t know the story of Chinese exclusion, it would be like saying you want to know about race relations in America but you’ve never heard of slavery,” Burns said.

Burns and Yu said they intend for the film to be an educational tool, and PBS and the Center for Asian American Media are distributing it to schools so that learning about Chinese exclusion becomes a given in U.S. history class.

“Just the way you know about the Fourth of July, you know about the Civil War, and you know about the Pilgrims — usually a ludicrously cartoonish way,” Burns said, “you’ll at least have a ludicrously cartoonish version of the Chinese Exclusion Act.”

“The Chinese Exclusion Act” premieres on PBS on Tuesday at 8 p.m. Eastern.

[ad_2]

Source link