[ad_1]

ASSOCIATED PRESS

SIOUX CITY, Iowa — Yidnekachew Yilma immigrated to the U.S. seven years ago from Ethiopia. On Tuesday evening, he was among a handful of voters inside a Lutheran church’s gymnasium, casting a ballot near a basketball hoop. He walked out into the cold and the wind, the sun setting over Sioux City, smiling. He felt proud.

“I got my citizenship two months ago, so this is the first time” to vote, he told HuffPost. “I’m excited.”

Yilma, 33, works at a meatpacking plant. The man who represents him in Congress, white supremacist Rep. Steve King, would rather people like Yilma not live in northwest Iowa, or anywhere else in America.

King is arguably the most bigoted member of Congress. For years, he’s parroted and promoted the propaganda of white nationalists and neo-Nazis, and openly associated with fascist and far-right figures at home and overseas. “Diversity is not our strength,” he once wrote in a tweet.

Yilma said he’d heard King didn’t like immigrants. He decided to vote for King’s Democratic opponent, J.D. Scholten, after seeing one of Scholten’s campaign ads on YouTube. “I trust him,” Yilma said.

In the week leading up to Tuesday’s election, to the shock of political observers, it seemed Scholten had a real shot at unseating King, an eight-term congressman who’s routinely won re-election by over 20 percentage points in this rural, deeply conservative corner of the Hawkeye State. One pre-election poll had shown Scholten trailing King by just 1 percentage point.

But by late Tuesday night, the dream of a Democratic upset here was over. Scholten — a towering, 38-year-old former minor league baseball player and paralegal with a shaved head — walked around his election night party at a hotel on the Missouri River. He hugged and thanked supporters, posed for selfies and did interviews with local TV stations.

As the party died down, Scholten was a couple of beers deep and feeling candid. Earlier, he’d done the polite and customary thing of calling King to congratulate him.

Congressional Quarterly via Getty Images

“Straight up, it sucked,” Scholten told HuffPost about the call. He’d lost to King by 3 percentage points.

“The difficult thing in all of it is why the Iowa I know, the Iowa I grew up in, continues to go for King,” he said. “And honestly, that’s the toughest question I have, and I still don’t have a good answer for it. It’s frustrating because, like, the bar of white nationalism, the bar of racism, the bar of anti-Semitism is so damn low. And we don’t have a representative who can cross that bar. And that’s difficult for me to grasp.”

King has never denied being a white nationalist. On Oct. 21 he even appeared to defend the term itself, telling a local TV host that, although “white nationalist” is “a derogatory term today, I wouldn’t have thought so maybe a year, or two or three ago.”

Yet on election night, over 159,000 people in Iowa voted for King anyway. And although there are multiple reasons for why King keeps winning here — including racism, name recognition, party loyalty and issues like abortion rights — it’s maybe more instructive to consider why King came so close to losing this time.

There are 70,000 more registered Republicans than registered Democrats in Iowa’s 4th Congressional District. President Donald Trump beat Democratic rival Hillary Clinton here by 27 points. That Scholten came within 3 points, or about 10,000 votes, of King is remarkable and shows he garnered support from Republicans.

“I’m voting for Scholten,” a middle-aged white woman said softly to HuffPost Monday night at a campaign rally for Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds. King, who had spoken at the rally, was standing just a few feet away. “He’s too extreme,” the woman, who asked not to be named, said of King.

Although King has long been a bigot, he’s been particularly transparent about his fascist beliefs during his eighth term in Congress. Just last month, King endorsed a mayoral candidate in Toronto who has recited the “14 words,” a neo-Nazi slogan. Also last month, HuffPost uncovered an interview that King had given to an Austrian publication associated with Europe’s neo-fascist “identitarian” movement.

In that interview, King pushed the anti-Semitic idea that the liberal, Jewish billionaire George Soros is funding what’s called the “Great Replacement,” the conspiracy theory that immigration from non-white countries spells the end of white European culture and identity. (It’s the equivalent of the “Jews will not replace us” chant at the deadly Charlottesville, Virginia, white supremacist rally last year.)

King had managed to espouse all this nonsense with little political consequence until late October, when the massacre of 11 worshipers at a Pittsburgh synagogue by a white nationalist brought King’s own white nationalism under heightened scrutiny. Two days after the shooting, the polling firm Change Research published a poll showing King leading Scholten by only 1 percentage point.

Suddenly the head of the National Republican Congressional Committee felt compelled to denounce King. Corporate campaign donors, under pressure for giving money to a bigot, ditched him. The Sioux City Journal, which had endorsed King in prior elections, endorsed Scholten, whose campaign was being inundated with donations: $640,000 in one 48-hour period.

Still, it’s hard to say how many voters abandoned King because of his bigotry. When King spoke at Gov. Reynolds’ rally Monday night, he wasn’t interrupted by a heckler calling him a racist. He was interrupted by a 44-year-old farmer, Dolf Ivener, upset over the price of soybeans.

“$7.50 for soybeans, I’m going to go broke because of you, Steve King!” Ivener yelled, before being escorted out of the rally. “I’m going to go broke because of you.”

Trump’s trade war with China, which King supports, has taken a real toll on farmers here. China bought 94 percent fewer soybeans this year from America than in 2017.

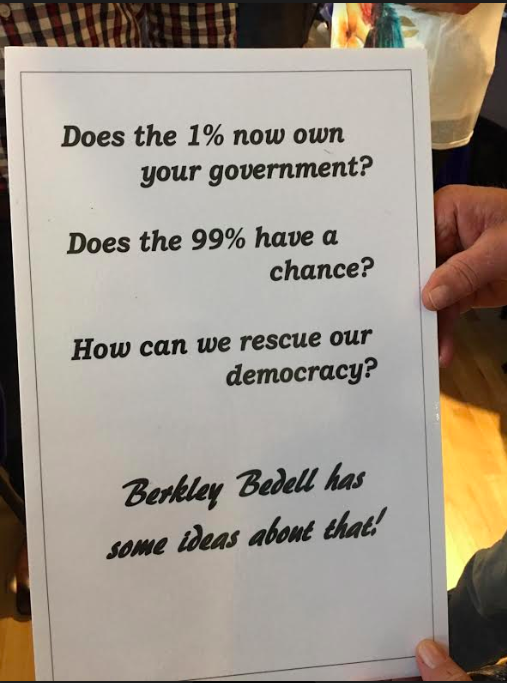

Scholten likes to remind reporters of the Midwest’s oft-forgotten history of progressive economic populism. In the 1980s, it wasn’t a far-right figure like King representing this part of Iowa. It was a Democrat named Berkley Bedell, one of Scholten’s political heroes. Bedell was a populist who focused on economic inequality. (Scholten keeps a photo on his phone of a Bedell campaign flyer from the ’80s: “Does the 1% now own your government? Does the 99% have a chance?”)

Courtesy of the J.D. Scholten campaign.

Scholten’s campaign, which refused to take corporate PAC money, focused less on King than it did on progressive economic policies: increasing the minimum wage (Iowa has one of the lowest minimum wages in the country), strengthening unions and fighting Big Agriculture, which is squeezing farmers here for every penny they’re worth.

“The average person in Congress is 58 years old with a net worth of a million dollars,” Scholten told HuffPost. “I’m different. I’m 20 years younger and about a million dollars short of that average because, you know what, I understand what it means to live paycheck to paycheck. I understand what it means to not have health care at times.” (Note: The median net worth in Congress is about $900,000. Over half of the members of Congress are millionaires.)

Scholten campaigned hard. For six months, he drove around in an RV he called “Sioux City Sue,” visiting voters in each of the district’s 39 counties, sometimes attracting hundreds of people to town halls in deep-red parts of the district. At night he slept in the RV, which he often parked at Walmarts. (King, meanwhile, barely campaigned here, buying his first TV ad only a few days before the election.)

Although Scholten was forceful in denouncing King’s bigotry on the campaign trail, he spent more time depicting King as an absent and ineffective representative.

It was a message that resonated with The Des Moines Register’s editorial board, which called its endorsement of Scholten “a no-brainer for any Iowan who has cringed at eight-term incumbent King’s increasing obsession with being a cultural provocateur.”

“In his almost 16 years in Congress, King has passed exactly one bill as primary sponsor, redesignating a post office,” the newspaper’s board wrote. “He won’t debate his opponent and rarely holds public town halls. Instead, he spends his time meeting with fascist leaders in Europe and retweeting neo-Nazis.”

HuffPost tried multiple times in Iowa to ask King’s campaign about why he was polling so poorly in this year’s midterm election campaign. At Reynold’s campaign rally on Monday, King’s son and campaign manager, Jeff King, blocked a HuffPost reporter from attempting to talk to King.

On election night, at King’s results-watching party, Jeff King asked HuffPost to leave the building. When asked why, he instructed HuffPost to refer to his quote in The Des Moines Register.

“We are not granting credentials to The Des Moines Register or any other leftist propaganda media outlet with no concern for reporting the truth,” read Jeff King’s quote.

Other alleged “leftist propaganda” outlets barred from covering King’s party included the conservative Weekly Standard and The Storm Lake Times, a Pulitzer-winning newspaper based in King’s district. It seemed King, known for being generous with reporters on Capitol Hill, was suddenly on the defensive.

With the close election results, there’s hope among progressives that Scholten could mount a successful race next time. He had no name recognition when he started this race. Now people know who he is.

On Tuesday night, Scholten’s phone lit up with text messages from big-name Democrats, including Sen. Corey Booker of New Jersey, congratulating him on running such a good race. Earlier he’d heard from House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi of California.

For now, though, Scholten won’t say whether he’ll run against King in 2020. All Scholten knew, he said, was that he wanted eggs for breakfast in the morning and that, for now, he’s just another “unemployed” and “single” thirtysomething in America.

“It just sucks,” Scholten said. “I wanted to beat him.”

[ad_2]

Source link